At the press conference following the meeting with the Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufarkis on 5th February 2015 German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble said:

“We have to appreciate their efforts and their situation, and above all we have to appreciate the progress that has been achieved in Greece over recent years. At the same time, however, we must say that the reason, the cause for the difficult journey to be undertaken by Greece, that the reasons for this are to be found in Greece, and not outside Greece, and definitely not in Germany.“

Content

An overview of Germany’s role in the crisis of the eurozone

This is not really a story of nations

Germans troubled economy prior to the single currency

German economic policy response to the single currency

Much of the commentary about the crisis in the eurozone is built on some common assumptions which are:

I want to challenge some of those assumptions. In particular the notion the way the German economy has been managed is responsible and admirable, and the idea that Germany has no responsibility for causing the crisis in the eurozone.

An overview of Germany’s role in the crisis of the eurozone

Germany has had a strong manufacturing sector based upon large premium branded companies (Volkswagen, Siemens, etc) for a long time, but that didn’t stop Germany from experiencing sluggish growth rates and high unemployment for nearly twenty years before the creation of the European Monetary Union in 1999. Germany had nearly 5 million unemployed by the time the deutschmark was replaced by the Euro, and during the 1990s Germany constantly ran trade and government deficits as it dealt with the costs and problems of German reunification.

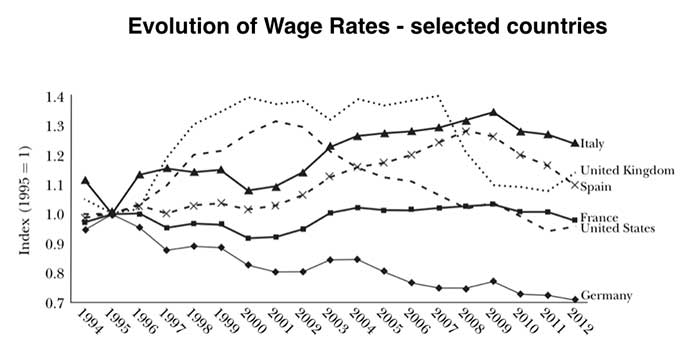

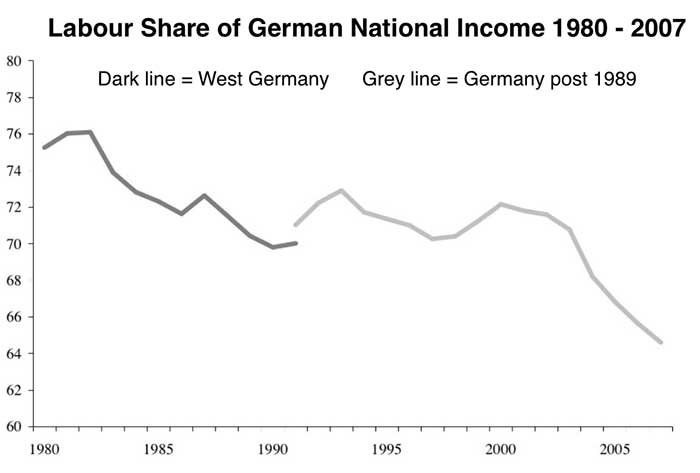

In 2002-3, in response to the low growth rates and high unemployment, a series of reforms were enacted. Collectively known as the Agenda 2010 reforms, they significantly reduced welfare provisions, made it easier to fire workers, encouraged part time and short term job creation, and drove down wage rates. As a result of the reforms the proportion of national income going to wages fell, unemployment fell, living standards stagnated and wage rates fell below those in other eurozone countries.

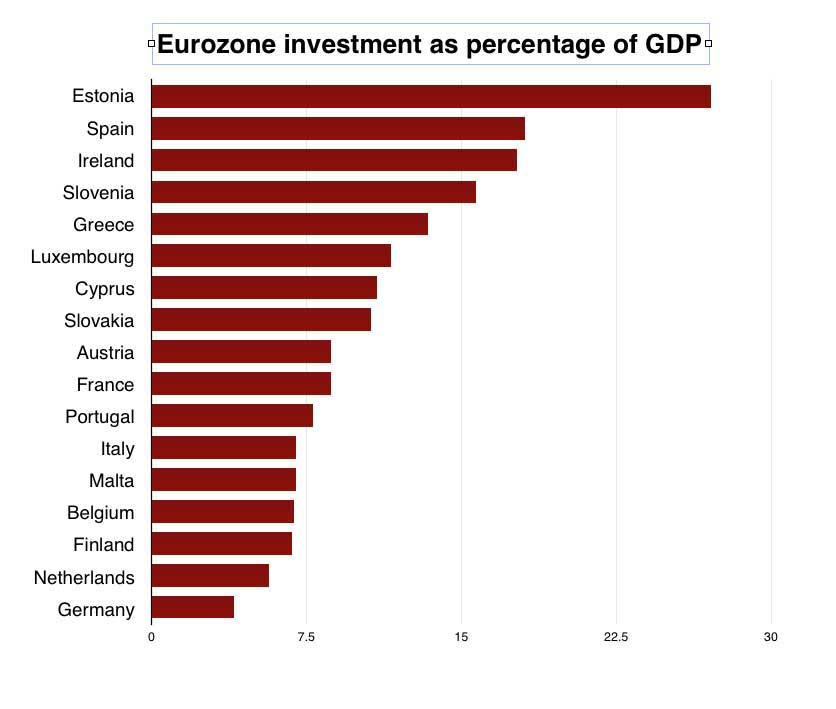

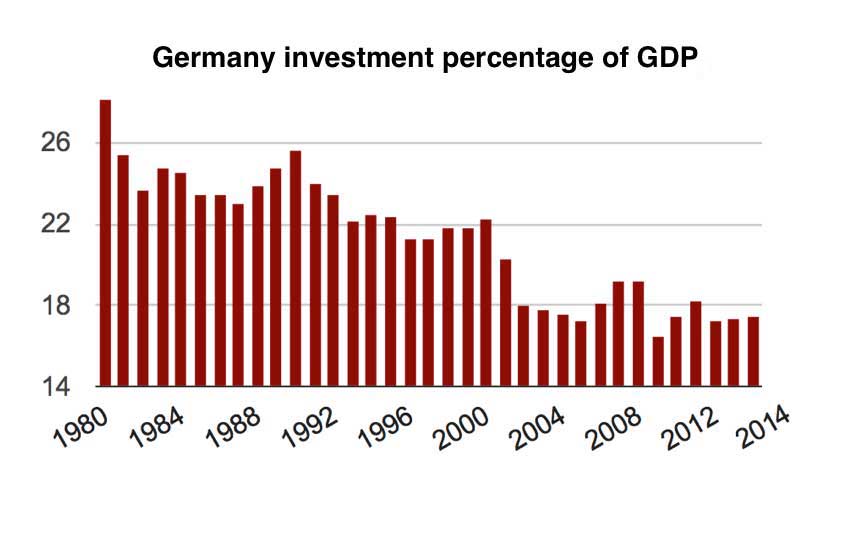

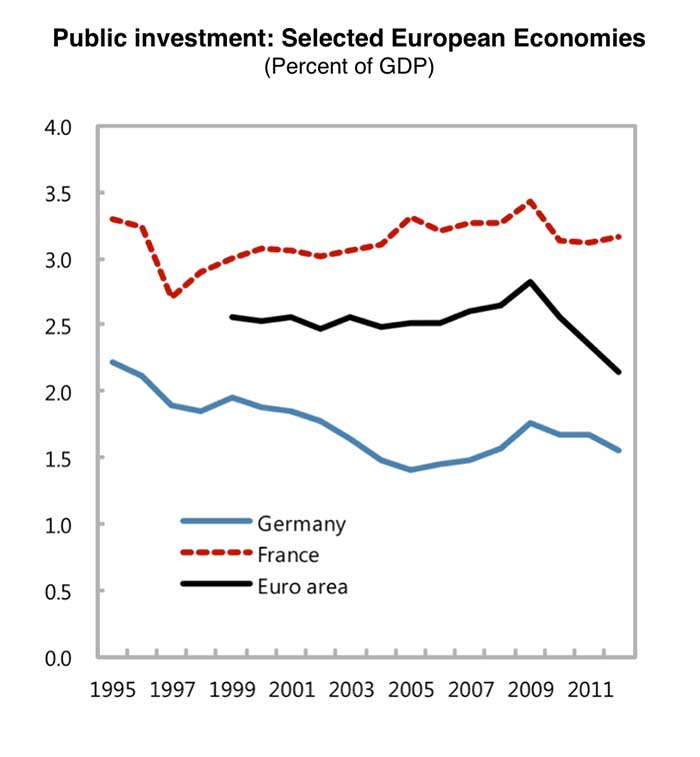

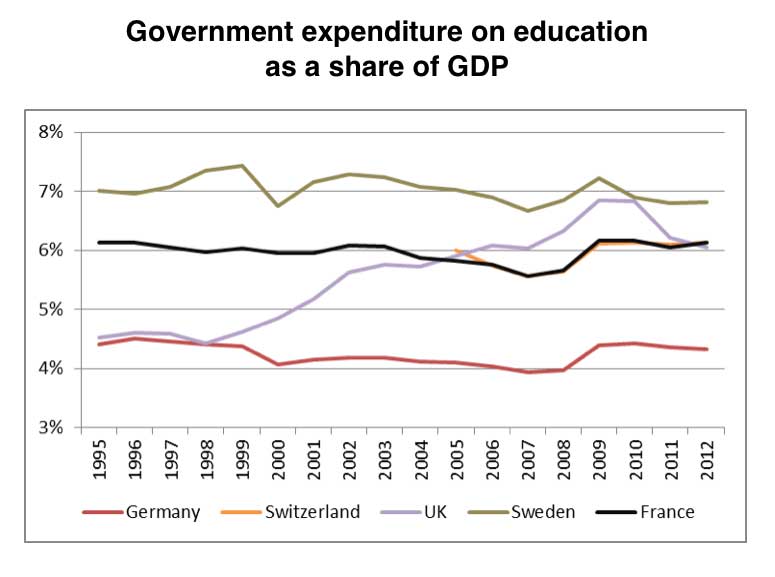

Germany has a comparatively low rate of investment compared to the rest of the Eurozone and to other developed economies. Although its economy is dependent on its manufacturing sector German domestic investment in both the private and the public sector has been low and falling for years. The level of public investment is below that required to maintain the infrastructure of the country and as a result German infrastructure is deteriorating.

The creation of the eurozone, combined with the reduction in domestic wage costs, greatly enhanced Germany’s exports. The Euro was undervalued in relation to what the German exchange rate would have been if it had still been using the deutschmark and this made German exports cheaper. The exchange rate of the Euro was too high for many weaker countries in the eurozone, and was above what it would have been if the drachma, peseta, escudo and lire had still been in use, and this made the exports of those countries more expensive.

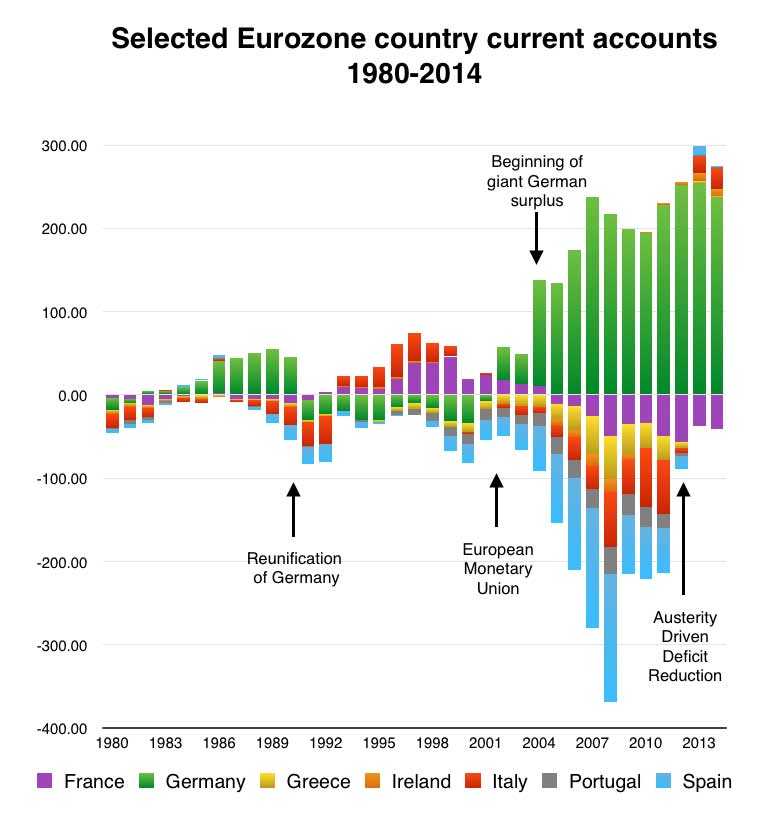

As a result of the German policy of suppressing wages, and because of the favourable impact of the Euro exchange rate, German exports have grown to unprecedented levels since the creation of the Euro. In recent years Germany’s trade surplus has been the largest in the world[1]European Commission ‘European Economy Occasional Papers’ No. 174 | March 2014 “Macroeconomic Imbalances Germany 2014” , bigger even than China’s, and exports have often accounted for nearly 50% of German GDP. A significant proportion of German exports flowed into the weaker economies of the eurozone where local goods were priced out of the market by the cheaper German imports. The weaker countries could no longer devalue their currency so the giant German surplus directly caused most countries in the eurozone to develop very large trade deficits.

The earnings from the huge German surplus were not spent domestically, as German worker’s wages and German domestic investment levels remained low and static even while export earnings grew by a very large amount. This failure to deploy it’s surplus domestically meant that as it’s exports grew Germany began to export large amounts of capital abroad as investors sought opportunities to grow their capital[2]The balance of payments is a statement of a country’s net financial transactions with other countries. This is normally broken down into the current account, which includes the visible balance of trade (the net difference between exports and imports of merchandise goods) and the invisible trade balance (payments and receipts for services such as shipping, banking and tourism); and the capital account, which measures the inflow and outflow of short-term and long-term capital (such as direct investment; income from securities, property, etc.). The visible and invisible trade balances, current account and capital account can be either in surplus (exports are larger than imports) or deficit (imports are larger than exports), but in principle there should be no surplus or deficit in the overall balance of payments.. A small proportion of this outflowing capital was used for direct investment (in factories in other countries for example) but the bulk was directed into the European financial system for investment and was loaned to banks in the weaker eurozone countries of Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Italy, Cyprus and Spain (from now on referred to as GIPICS), sometimes via intermediary banks in the UK and France.

As this river of German funded credit began to flow into the financial system interest rates across the eurozone were plummeting. In the years before the crisis of 2007 interest rates across the Eurozone harmonised and settled at a much lower level. The creation of the single currency convinced the financial sector that government borrowing was now a very safe investment across the eurozone and as a result the costs of borrowing for many government fell to historically low levels (Greece and Italy being good examples). Around the time the Euro was being created the EU also deliberately engineered changes to the global Basil II banking regulatory framework so that eurozone government borrowing was categorised as being risk free, and eurozone interbank lending was categorised as being almost risk free. As a result if banks lent to eurozone governments or other eurozone banks they did not have to keep capital in reserve as insurance against defaults. This meant that lending to eurozone governments and banks became very attractive and the capital flowing out of Germany looking for safe investment began to be loaned across the Eurozone in large quantities to governments, companies and individuals. Based on the flow of German capital credit in the Eurozone became cheap and plentiful.

The result of the flood of cheap German capital flowing into eurozone countries was a commercial boom and the peripheral countries of Europe (GIPICS) all saw growth rates much higher than Germany in the years leading up to the crash of 2007. The massive credit flows into GIPICS meant that private and business debt escalated, consumption levels rose and the booming demand for labour made wage rates increase. The rising wages inflated local prices and thus made cheaper German imports even more attractive. So as the weaker eurozone economies of GIPICS apparently began to boom and grow, their domestic businesses were actually becoming less and less competitive as more and more German imports were sucked in. This in turn increased the Germany’s trade surplus, which increased the amount of cheap German capital flowing into GIPICS, and so the imbalances grew ever bigger and became self reinforcing. In countries like Ireland and Spain huge speculative property bubbles began to inflate. In Greece and Italy huge government debt inflated. This was all fuelled by cheap capital flowing out of Germany.

This pattern of imbalances was mirrored at a global level by a similar pattern of surpluses and capital flows involving surplus-generating countries such as China, Japan and the oil exporters, and deficit countries, notably the USA. The entire global economy and finance system became inflated by giant flows of speculative capital. It was planet Ponzi and Germany was, along with China, was one of the biggest drivers inflating the unsustainable economic bubbles.

By the time the boom went bust in 2007 giant mountains of debt had been created across the weaker economies of the eurozone. The boom could only be sustained by a continuous flow of German capital but in 2007 the entire global financial system shuddered and came to sudden stop. This meant the flow of German capital into the peripheral eurozone countries suddenly stopped which popped the property bubbles in Spain and Ireland and this made many banks with huge stakes in the property business instantly insolvent as the value of their assets collapsed and the quantity of bad debts on their books exploded. The ending of cheap capital flows and the increased uncertainty in the financial markets began to force up the costs of refinancing government debt in GIPICS. The previously harmonised interest rates benign to split apart as the cost of borrowing for some governments began to get more expensive. The announcement that the Greek government had been lying about how much money it was borrowing sent a wave of fear through the financial markets and the costs of borrowing for many weaker eurozone countries suddenly became ruinously expensive. Countries such as Greece and Italy found themselves paying huge rates of interest to roll over their loans and as a result their debt mountains began to grow uncontrollably.

The bursting of the property bubbles in Ireland and Spain threatened the banking system in those countries with collapse so the Irish and Spanish government bailed out their banks and this meant that both governments now had a mountain of public debt. The European Central Bank, other EU governments and the IMF loaned money to GIPICS and almost all that money was given to banks to pay off their bad loans and prevent widespread banking collapses. Private debt became public debt. The result of the crisis was that GIPICS were now deeply in debt with shrinking economies and soaring unemployment, and because the banking system was very fragile (because many banks were still holding a lot of potentially bad debt) credit flows remained low.

The global economy, including the eurozone, all sank into a deep recession as result of the financial shock and the ending of global credit flows.

At this point one response could have been to combine an EU supervised reform program in the debtor nations with a German policy of reducing it’s surplus, mostly by increasing German wage rates, so that increased German demand for imports could have been used to help the debt stricken nations to grow their economies, and higher German wages would have raised costs in Germany thus making the exports of the debtor nations more competitive. This could have been combined with a moratorium on public debt repayment and perhaps the writing off of a significant chunk of the debt. The eurozone could have been nursed back to growth by a German inflation. A generalised attempt to rebalance the entire eurozone economic space could have been undertaken. This option was not chosen by the German government, which by then was the dominant player in formulating EU economic policy, reflecting the deep German aversion to inflation.

The German position is that the problems across there eurozone are not their fault, that their giant trade surplus and their history of massive lending (to what turned out to be mostly wildly speculative and wasteful ventures) is not part of the problem. For Germany all the problems lie within the weaker economies who should drive down their public spending, reduce wages and social costs, and shift to running a trade surplus. This is the currently consensus position of the EU, led politically by the Germans, in relation to dealing with the crisis. The result has been a prolonged slump, high unemployment and declining living standards. Its true that as a result of this policy trade deficits in GIPICS have almost vanished but this is not the result of an export boom but rather is the result of collapsing imports caused by collapsing incomes.

Germany remains committed to it’s low wages, low investment, export orientated economic model. Germany’s trade surplus remains extremely high and is now the largest in the world. Even as it has tried to shift to new export markets to replace shrinking demand in the eurozone it has continued with high levels of exports to GIPICS. In 2012 Germany’s trade surplus with the eurozone’s deficit nations (France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus and Ireland) still came to 54.6 billion Euro despite the sharp decline in imports in these crisis-hit nations. Germany has also reoriented it’s exports to other countries outside the eurozone. This has been aided by the Chinese response to the 2007 crisis which was to raise its rate of internal investment to an unparalleled level and this in turn sucked in German imports. However China’s frenzy of domestic investment appears to be coming to an end as it experiences its own speculative and property bubbles, and this means that Germany may well find it harder to maintain its trade surplus at previous levels.

The overall benefit of the German economic model has been low. Much of the surplus it generated via it’s exports has been frittered away through bad loans to speculative activities. Over and above the money spent directly bailing out the banking system Germany has lost an additional 400 billion Euro in external private bad debt written off since the crash of 2007. It’s own workers have suffered wage stagnation and a shift to less secure and low wage employment. German domestic investment is still very low by comparison with other developed countries. It’s investment in infrastructure remains below replacement levels and so the fabric of the nation slowly deteriorates. The eurozone is gripped by a German led policy of deflation so growth rates are low and in some parts of the eurozone the economy continues to shrink as unemployment reaches record highs. European solidarity and enthusiasm for the European project has declined sharply as a result of the continuing economic problems which are being blamed on the Euro. Germany GDP is only growing very slowly.

The decision by Germany to allow a massive trade surplus to develop, mirrored by massive capital exports, in the first decade of European Monetary Union was highly irresponsible and reckless. The German surplus, and accompanying German capital exports, was the key factor in the destabilisation of the eurozone. Although Germany cannot revalue it’s currency to rebalance its trade relationship with the rest of the eurozone it could achieve the same effect by allowing domestic costs to inflate. But Germany is ideologically and politically phobic about inflation and so that obvious solution to the eurozone imbalances is blocked. Instead all rebalancing is being be done by the weaker countries.

It was not the German people who lent money to the Greek, Irish, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian people. The policies implemented by Berlin that resulted in the huge swing in Germany’s current account from deficit in the 1990s to surplus in the 2000s were imposed at a cost to German workers, and have been at least partly responsible for Germany’s extremely low productivity growth, most of Germany’s growth before the crisis can be explained by the change in its current account, rather than by rising productivity.

Moreover because German capital flows to the weaker economies ensured that GIPICS inflation exceeded German inflation, lending rates that may have been “reasonable” in Germany were extremely low in GIPSIC, perhaps even negative in real terms. With German, French, UK, Irish, Greek, Italian and Spanish banks all offering nearly unlimited amounts of extremely cheap credit (largely funded by German capital exports) to all takers across the eurozone, the fact that some of these borrowers were terribly irresponsible was not an imprudent, or even surprising “choice.” If you shower businesses and individuals with almost unlimited cheap credit quite a bit will be spent unwisely. That’s what always happens in such circumstances.

All trade surpluses have to be matched by trade deficits elsewhere so the idea that everyone can have a simultaneous trade surplus is absurd. It is hard to believe that the way that GIPICS are going to revive is through adopting the German model of slashing wage rates and building exports economies founded on large trade surpluses. Which deficit countries would they export to? Countries like Greece don’t really have exports industries (other than tourism). And even if the weaker countries could become smaller versions of Germany would that be a good thing given that the Germany model has delivered so few benefits to either the average German worker or the economy of the European Union? Germany is part of the economic problem and not the model for it’s solution

In October 2013, the US Treasury Department’s currency report noted:

“Within the euro area, countries with large and persistent surpluses need to take action to boost domestic demand growth and shrink their surpluses. Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany’s nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany’s anaemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy. …Stronger domestic demand growth in surplus European economies, particularly in Germany, would help to facilitate a durable rebalancing of imbalances in the euro area”

This is not really a story of nations

The euro crisis is a crisis of Europe, not of European countries. It is not a conflict between Germany and debtor eurozone countries about who should be deemed irresponsible, and so who should absorb the enormous costs of nearly a decade of mismanagement. There was plenty of irresponsible behaviour in every country. It is absurd to think that when German banks, assisted by US, UK, French, Spanish, Italian, Irish and Greek banks, poured nearly unlimited amounts of money into countries at extremely low or even negative real interest rates, especially once these initial inflows had set off stock market and real estate booms, that there was any chance that these countries would not respond in the same dangerous way that every country in history, including Germany, had responded under similar conditions.

Clearly the households and businesses in GIPICS, along with some of their governments, behaved in aggregate, in retrospect, with astonishing abandon. But could they have done otherwise – did they have a choice? Almost certainly not. Germany did not when it was on the end of a similar capital inflow in the 1920s, and I don’t think there are many, if any, cases of countries that were able to absorb productively such massive inflows. In every case I can think of, massive capital inflows were accompanied by speculative bubbles and financial crises. Is it reasonable to insist that the failure of GIPICS to choose a path that no other country in history seems ever to have chosen indicates greater irresponsibility on the part of the borrowers than of the lenders? As long as there is a widely diverse range of views among individuals and businesses in GIPICS about prospects for the future, as long as there is a mix of optimists and pessimists, or as long as there are varying levels of financial sophistication, it would have been historically unprecedented if at least some did not respond foolishly to aggressive offers of extremely cheap credit, especially once this cheap credit had set off a real estate boom.

Before the crisis German workers were forced to pay to inflate the bubble in the eurozone periphery by accepting very low wage growth, even as the European economy boomed. After the crisis workers in the eurozone periphery were forced to absorb the cost of deflating the bubble in the form of soaring unemployment. But the story doesn’t end there. Before the crisis, banks from across Europe eagerly sought out borrowers in the eurozone periphery and offered them unlimited amounts of extremely cheap loans, mostly funded by German capital exports. Somewhere in the fine print I suppose its possible the lenders suggested that it would be better if these loans were used to fund only highly productive investments but I doubt it. Many of them didn’t, and because they didn’t, eurozone banks – mainly the German banks who originally exported excess German savings – must take very large losses as these foolish investments, funded by foolish loans, fail to generate the necessary returns.

It is no great secret that banking systems resolve losses with the cooperation of their governments by passing them on to middle class savers, either directly, in the form of failed deposits or higher taxes, or indirectly, in the form of financial repression.[3]Financial repression is a term used to describe measures sometimes used by governments to boost their coffers and/or reduce debt. These measures include the deliberate attempt to hold down interest rates to below inflation, representing a tax on savers and a transfer of benefits from lenders to borrowers. Financial repression is also used to describe measures to facilitate a domestic market for government debt and the imposition of capital controls. The combined effect of all these measures means funds are channeled to the government that would otherwise flow elsewhere. Financial repression in China is said to be the cause of its huge accumulation of foreign currency reserves. Similarly western governments were being accused of financial repression following the 2008/2009 financial crisis as they embarked on measures including quantitative easing, capping interest rates and creating more domestic demand for their own bonds. Eurozone banks must be recapitalised in order that they can eventually recover from the inevitable losses, and this means either many years of artificially boosted profits in the finance sector on the back of middle class savers, or the direct transfer of losses onto the government balance sheets, with household taxpayers across the eurozone covering the debt repayments.

It is absolutely wrong for Volker Kauder, the parliamentary caucus leader of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, to say that “Germany bears no responsibility for what happened in Greece. The new prime minister must recognise that.” There was indeed plenty of irresponsible behaviour on both sides, during which time wealth was transferred from workers of both countries to create the boom and to absorb the subsequent bust, and wealth will be transferred again from middle class households of both countries to clean up the resulting debt debacle.

Put differently, there is no national virtue or national vice here, and there is no reason for the European crisis to devolve into right-wing, nationalist extremism. The financial crisis in Europe, like all financial crises, is ultimately a struggle about how the costs of the adjustment will be allocated, either to workers and middle class savers on the one hand, or to bankers, owners of real and financial assets, and the business elite on the other.

Some Background Detail

Germans troubled economy prior to the single currency

Germany has had a rocky economic track record over the last three decades characterised by lengthy periods of stagnation and low growth. Following the ending of the post war ‘miracle’ phase of rapid growth West German economic growth was sluggish for most 1980s. The second half of the 1980s saw a gradual recovery which unfolded in a short boom at the end of the decade. During the same period the East German economy was spiralling into a debt fuelled collapse. Following the fall of the wall in 1989 and abrupt German reunification there was a brief period of contraction, resulting mostly from the sharp shock in the east caused by exposure to full global competitive pressures. Then in the early 1990s there was a brief mini-boom which only lasted a couple of years. Through much of the 1990s German growth was lower than the EU average, unemployment was high and Germany ran both a public sector deficit and a current account deficit as the costs of reunification were absorbed. Germany suffered a significant erosion of its manufacturing base in the 1990s as the manufacturing share in total value added decreased from 29 per cent of GDP in 1991 to 24.1 per cent in 1996.

The problems of the German economy were partly the result of the significant appreciation of the Deutschmark in the wake of the crisis of the European Monetary System (EMS) in 1992, which forced up the price of German exports in world markets and lowered the costs of imports competing with domestic enterprises. The competitiveness of the German economy also suffered from an increase in wages and non-wage labour costs driven by rising social security contributions after the extension of the West German social security system in the East (social union). As a result of the ongoing low growth German unemployment continued to increase up to 1997, when more than 3 million people were registered unemployed. By the end of the 1990s German was being described as the ‘sick man of Europe’.

German economic policy response to the single currency

Following the creation of the European Monetary Union in 1999 the German economy continued to experience problems and GDP stagnated from spring 2001 into 2004. This marked the longest stagnation in postwar Germany. This slack economic period was accompanied by rising unemployment and a fall in investment levels. Unemployment increased from 3.85 million in 2001 to over 5 million in 2005. Investment declined from 2001 to 2004. Construction investment declined year by year from 2000 into 2005. In 2005 it amounted to only 76 per cent of the peak level of 1995. Investment in machinery and equipment plummeted in 2001 and 2002.

The German Social Democrat government under Gerhard Schroeder responded to the problems of economic stagnation and high unemployment with a series of very significant policy initiatives which were designed to restore German industrial competitiveness and boost exports. At the same the there was a sustained attempt to reduce government spending in order to meet the strict deficit limiting rules of the new eurozone, rules that were in place largely at German insistence.

After 2003 the entire orientation and dynamic of the German economy began to change as the government introduced a raft of new policies to improve international competitiveness by deliberately depressing wages through the weakening of labour protection regulations. The competitiveness of German economy also improved because it was now sheltered inside a currency union that had a more favourable exchange rate than had been possible when German had its own currency. As a result the reductions in wage costs, which both reduced costs and reduced domestic demand, and assisted by the new favourable Euro exchange rate, the German economy began a dramatic shift towards very high levels of exports of manufactured goods. This shift to very high levels of exports was to have profound implications for the stability of the eurozone as whole, something explored in detail later in this article.

As a result of these new economic policies the economy returned to growth but German growth rates were still lower than the eurozone averages in the years leading up to 2007 crisis. However the labour market and welfare reforms meant that unemployment fell significantly. The number of unemployed decreased from more than 5 million in 2005 to 3.5 million at the end of 2007. The government deficit also decreased.

The labour market reforms announced by Social Democratic Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in 2003 and known as Agenda 2010 caused the biggest transformation in German labour regulation and social policy since the war by relaxing the rules concerning the firing of workers, making it easier to create part time and short duration employment, and by introducing restrictive new regulation concerning unemployment benefit and social security.

The Key components of Agenda 2010 were

Decreasing the duration of unemployment benefit from 32 to 12 months

Decreasing barriers to implementing layoffs for certain categories of workersMerging social security and unemployment welfare systems, Sozialhilfe and Arbeitslosenshilfe, into a single system corresponding to the most modest of the predecessors, enforcing beneficiary employment searches and acceptance rate more stringently than in the past

Allowing low income employment/jobs to be combined with total or partial welfare benefits

As result of the Agenda 2010 reforms the proportion of national income going to wages had declined by 2008 to a 50-year low of only 64.5%. According to a recent study by the University of Duisburg-Essen’s Institute for Work, Skills and Training, those earning less than €9.15 (£7.40) per hour actually increased by 2.3 million to 8 million between 1995 and 2010. Of the total workforce, 23% of employees make less than €9.15 per hour and the gross monthly salary for 800,000 full time workers is less than €1,000 (£808). According to an April 2012 OECD report, “Germany is the only [EU] country that has seen an increase in labour earnings inequality from the mid 1990s to the end 2000s driven by increasing inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.” The report goes on to point to “a set of reforms in 2003 meant to increase the flexibility of the labour market” which helps to explain the “wage moderation”.

Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development shows low-wage employment accounts for 20 percent of full-time jobs in Germany compared to 8.0 percent in Italy and 13.5 percent in Greece.

Job growth in Germany has been especially strong for low wage and temporary agency employment because of deregulation and the promotion of flexible, low-income, state-subsidised “mini-jobs.” Employers have little incentive to create regular full-time jobs if they know they can hire workers on flexible contracts. One out of five jobs is a now a “mini-job,” earning workers a maximum 400 euros a month tax-free, and for nearly 5 million this is their main job. Regular full-time jobs are increasingly being split up into mini-jobs, with workers frequently being fired and rehired as business activity rises and falls.

The number of full-time workers on low wages, defined as less than two thirds of middle income, rose by 13.5 percent to 4.3 million between 2005 and 2010, three times faster than other employment, according to the Labour Office. By 2011 jobs at temporary work agencies had reached a record high of 910,000, triple the number from 2002 when Berlin started deregulating the temp sector. Germany, unlike almost all other EU countries, has no national minimum wage legislation and one Euro an hour and even 50 cent an hour jobs are relatively common in the poorer regions.

The Agenda 2010 reform package has also weakened the traditional sectoral multi-employer system of wage bargaining at the regional level: coverage of sectoral agreements amongst employees declined from 70% in 1996 to 53% in western Germany and only 36% in eastern Germany by 2012. Privatisation, deregulation, labour reforms and the growth of temporary employment and outsourcing have all undermined the position of employees, particularly in unskilled jobs.

The number of Germans living below the poverty line has increased from 11% in 2001 to 14% in 2007[4]OECD Income Inequality In The European Union Economics Department Working Papers No. 952 Page 9 “from the mid- 1990s to 2008 when 30% of the poorest Germans actually had negative real income growth. Koske et al. (2012) note Germany is the only country that has seen an increase in labour earnings inequality from the mid 1990s to the end 2000s driven by increasing inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.”. According to 2007 government statistics, one out of every six children was poor, a post-1960-record, with more than a third of all children in big cities like Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen living in poverty. The fact that 50% of the population has no forms of savings or assets shows that low pay is not just a problem restricted to the unskilled sector, either. Children, too, are suffering. In Unicef’s latest report on child poverty in rich countries, Germany is ranked 15 in terms of child deprivation, behind the UK (nine) and Spain (12)[5]OECD Working No. 952. Income inequality in the European Union. .

Germany’s exceptional growth in exports after the creation of the eurozone is often presented as being the result of increased German productivity. However this increase is mostly the result of lowering wage costs not the result of real improvements in the system of production resulting from productive investment.

German investment is low by EU and developed economy standards. The share of investment in GDP is one of the lowest among industrialised countries. It has been declining rapidly, from an average of 23 per cent in the 1990s to less than 17 per cent today, well below the 21 per cent average for industrialised countries. In the private sector, domestic machinery investment is at a record low of 6.2 per cent of GDP. Although German companies are investing heavily overseas, notably in eastern Europe and China, foreign direct investment is only about 1 per cent of GDP, on World Bank estimates, so that alone does not explain the low domestic investment levels.

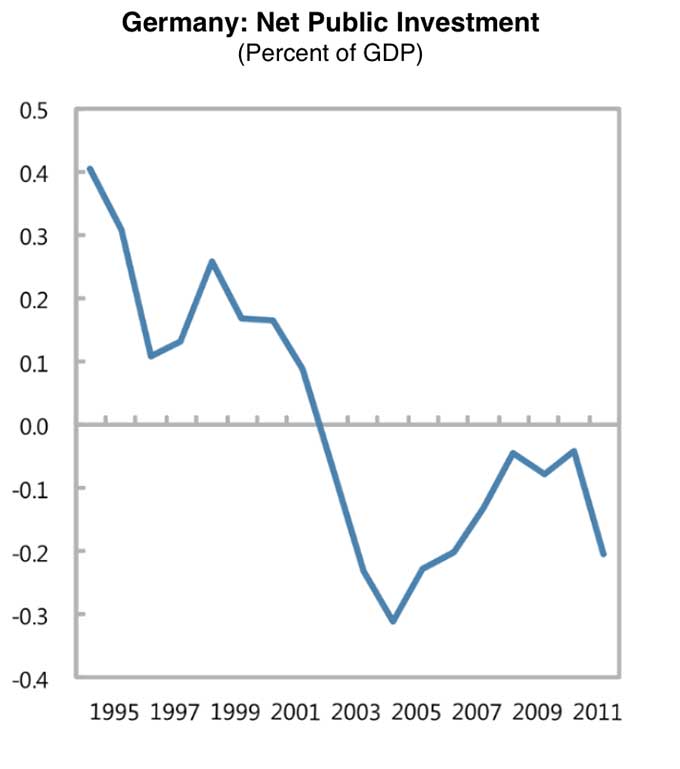

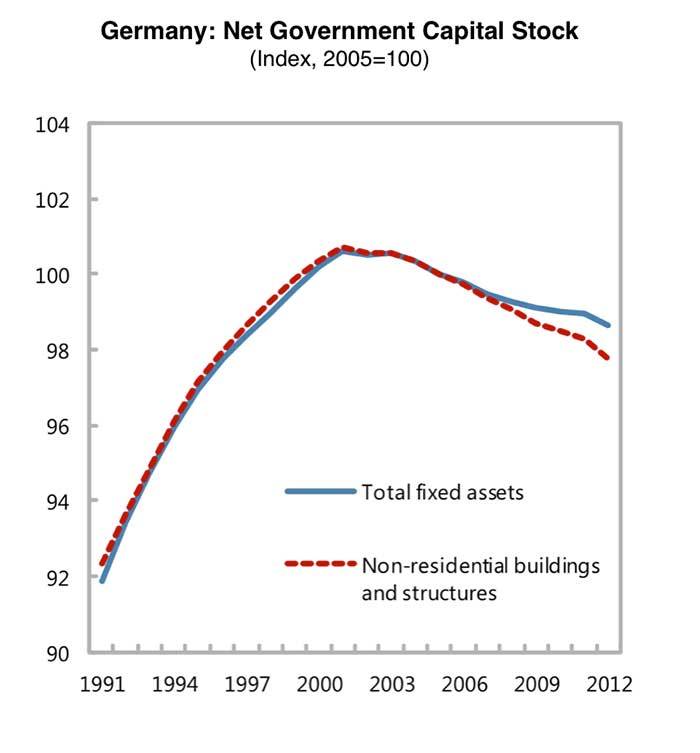

Along with a decline in private investment, government investment in infrastructure has also declined, driven down by Germany’s commitment to reducing (and even eliminating) its public sector deficit. The German infrastructure investment shortfall between 1999 and 2012 amounted to about 3 percent of GDP, the largest “investment gap” of any European country. If one looks only at the years from 2010 to 2012, the gap, at 3.7 percent, is even bigger. Just to maintain the status quo and achieve reasonable growth, the government and business world would have to spend €103 billion more each year than they do today. Nearly 15 years ago, the state’s net assets still corresponded to 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). When adjusted for inflation, this amounts to nearly €500 billion. By 2011, this had dwindled to 0.5 percent of GDP, or a mere €13 billion, primarily due to systematic neglect

.Source: IMF Country Report No.14/217 June 2014

Source: IMF Country Report No.14/217 June 2014

Source: IMF Country Report No.14/217 June 2014

Germany’s giant trade surplus

From the beginning of the eurozone the German current account surplus has grown at a blistering pace, really taking off after the Agenda 2010 labour reforms introduced in 2003. Since then the surplus has often matched, and has recently started to exceed, the Chinese surplus as the biggest in the world.

As the German surplus grew so did equally large deficits across the eurozone and there has been a lively debate about the link between the huge German surplus, the outflow of German capital exports and the simultaneous appearance of huge matching deficits in other eurozone countries . It is sometimes argued that the growth of deficits across the eurozone were not driven by the German surplus however, it would be an astonishing coincidence that so many countries decided to embark on consumption sprees at exactly the same time. It would be even more remarkable, had they done so, that they could have all sucked money out of a reluctant Germany while driving interest rates down. It is very hard to believe, in other words, that the enormous shift in the internal European balance of payments was driven by anything other than a domestic shift in the German economy.

Once inside the single currency zone old exchange rates ceased to function but it is still possible to calculate shifts in relative competitiveness, shifts that are the result of difference in costs (particularly labour costs) and shifts in local inflation rates and thus shift in relatives prices. The European Commission compiles so-called ‘harmonised competitiveness indices’ for eurozone economies. These are the member-states’ real exchange rates in anything but name. They show that between the beginning of 1999 and the end of 2011 Germany’s costs fell by almost 20 per cent relative to other weaker eurozone countries and the main reason was very low wage increases and hence weak inflation.

By 2009, the European Commission calculated that, if national exchange rates had still been in existence, the Spanish peseta. Portuguese escudo and the Greek drachma would have had to depreciate by 10 – 15%, and the German deutschmark would have needed to revalue by a similar amount.

Notes

| ⇧1 | European Commission ‘European Economy Occasional Papers’ No. 174 | March 2014 “Macroeconomic Imbalances Germany 2014” |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | The balance of payments is a statement of a country’s net financial transactions with other countries. This is normally broken down into the current account, which includes the visible balance of trade (the net difference between exports and imports of merchandise goods) and the invisible trade balance (payments and receipts for services such as shipping, banking and tourism); and the capital account, which measures the inflow and outflow of short-term and long-term capital (such as direct investment; income from securities, property, etc.). The visible and invisible trade balances, current account and capital account can be either in surplus (exports are larger than imports) or deficit (imports are larger than exports), but in principle there should be no surplus or deficit in the overall balance of payments. |

| ⇧3 | Financial repression is a term used to describe measures sometimes used by governments to boost their coffers and/or reduce debt. These measures include the deliberate attempt to hold down interest rates to below inflation, representing a tax on savers and a transfer of benefits from lenders to borrowers. Financial repression is also used to describe measures to facilitate a domestic market for government debt and the imposition of capital controls. The combined effect of all these measures means funds are channeled to the government that would otherwise flow elsewhere. Financial repression in China is said to be the cause of its huge accumulation of foreign currency reserves. Similarly western governments were being accused of financial repression following the 2008/2009 financial crisis as they embarked on measures including quantitative easing, capping interest rates and creating more domestic demand for their own bonds. |

| ⇧4 | OECD Income Inequality In The European Union Economics Department Working Papers No. 952 Page 9 “from the mid- 1990s to 2008 when 30% of the poorest Germans actually had negative real income growth. Koske et al. (2012) note Germany is the only country that has seen an increase in labour earnings inequality from the mid 1990s to the end 2000s driven by increasing inequality in the bottom half of the distribution.” |

| ⇧5 | OECD Working No. 952. Income inequality in the European Union. |