Both the Irish and UK governments say that they don’t want a closed border in Ireland and both would like the post Brexit border to be as open as it is now.

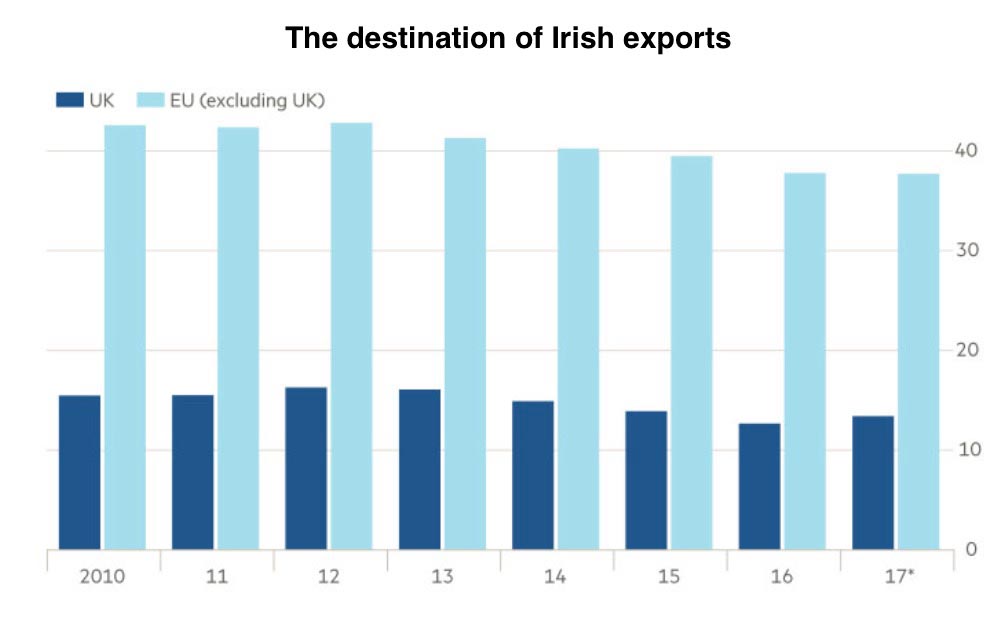

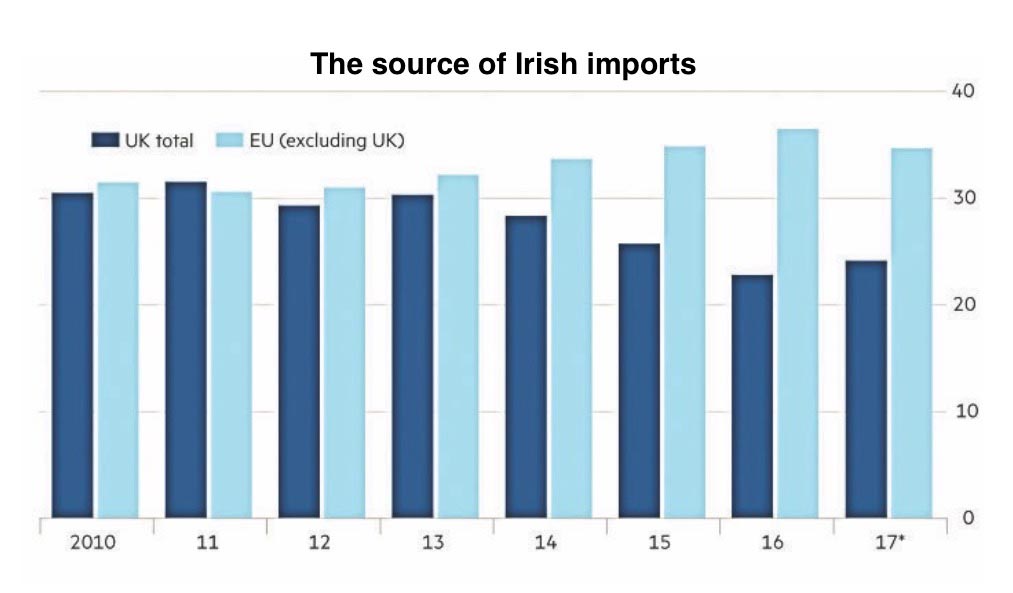

There is more at stake than just the border in the north. The UK is by far Ireland’s largest trade partner (see the charts below) so any interruption of, or obstacles to, bilateral UK and Irish trade would have a major, possibly devastating effect on the economy of Ireland (still carrying a huge debt burden). In addition there is the fact that two-thirds of the major exporters in Ireland ship goods via Britain on their way to European and global markets, according to the Irish Exporters Association. Transiting through Britain allows Irish companies to take advantage of short sea crossings from Ireland, extensive UK motorways and the Channel tunnel to France. Crucially, the absence of border checks saves trucks time at British ports. But with the UK government committed to leaving Europe’s customs regime, there are concerns that longer queues and higher costs could damage an Irish economy that still bears the scars of the financial crisis.

a) The UK proposal which is for a virtual electronic border using online notification of imports and exports plus number-plate recognition technology instead of physical inspections. The UK argues that most lorries could cross the border without checks in a system that could be a template for a new UK customs deal with the EU and could thus also facilitate the transit of Irish goods through the UK onward to the EU.

But Ireland has shut down all discussion on the feasibility of a virtual border.

A key issue for the virtual border option is one of compliance of goods with EU (and eventually separate UK) trading standards. On day one of a virtual border all goods would still comply with EU standards because the UK would have incorporated into UK law all pre-existing EU standards. Things will get more complicated as time passes if UK and EU standards drift apart (for example if the UK decided to lift the EU limit on the power consumption of vacuum cleaner engines, or decided to legalise the sale of incandescent light bulbs, etc). How well a virtual border would work over time as standards diverge is unclear.

b) The Irish proposal, favoured by Brussels is to move the border to the mainland UK. The Irish view remains that the best way of avoiding physical checks on the frontier is for Northern Ireland to remain in Europe’s customs union or apply rules similar to it. But London wants to leave the customs union, and it rejects the idea of Northern Ireland remaining in it, on the grounds that it would a create a border within the UK.

There are two major problems with this option:

First it does not solve the wider problems of bilateral Irish-UK trade and does not solve the problems of the transit of Irish goods through UK transport system onwards to the EU.

Second the DUP would never agree such a deal and they have the power to bring down the minority UK government. Its possible that some in Dublin and Brussels want to see the UK government fall and might welcome the possibility of a Labour Party government. Jeremy Corbyn, and even more so John McDonnell, have always been keen supporters of a united Ireland so an all Ireland border shutting the north in with the south might have its attractions for the Labour leadership.

c) Mutual Assured Destruction – otherwise known as a Hard border. The option no one wants but the option that will occur if neither side shifts its position and there is, as a result of an Irish veto, a hard Brexit. The frontier today is invisible and there are no border checkpoints, reflecting huge strides made since the Good Friday Agreement signed in 1998. The concern remains that any new border posts after Brexit would damage the economy and become targets for disaffected paramilitary groups bent on a return to violence.

Philip Rutnam, permanent secretary of the UK’s Home Office, told a parliamentary committee in October that use of British troops to police UK borders could not be ruled out if there was no Brexit deal, though he stressed that use of the army would be an “absolute last resort”.

Over the next couple of weeks one side or the other will blink – in which case trade talks can start and a hard Brexit may be averted – or neither will blink in which case there will be an Irish veto leading to a hard brexit.