At the pivotal November 2014 Opec meeting Saudi Arabia embarked on an oil-price-cutting strategy, which is what refusing to reduce production to support prices amounted to. This Saudi strategy had several sets of opponents in its crosshairs. The first was US frackers, who posed an intermediate-term threat as the shale boom moved the USA from being a net importer of oil to being the world’s largest oil producer, and now to being an oil exporter. At the same time the USA is also moving to significantly increase liquid natural gas exports, particularly to Europe as the EU moves to end dependency on Russian gas. The second target for the Saudi cheap oil strategy was the heavily subsidised renewable energy sector, which becomes much less attractive if conventional energy becomes cheap. The third, and probably most important, target was Saudi Arabia’s geopolitical opponents, the most important being Russia and Iran. Unfortunately for the Saudis they have lost control of their strategy and find themselves financially distressed in a world of cheap oil.

Since the Saudi strategic shift in late 2014 the price of oil has plummeted 70 per cent from its June 2014 highs of $120 a barrel to the current trough of just over $30 a barrel, and shale has yet to throw in the towel. Constant productivity gains have meant that US output has only just now begun to fall, from a still impressive total of over 9m barrels of day. In response, the Saudis have continued on with their game of energy chicken, forcing Opec to maintain present levels of production, despite howls of protest from countries as far afield as Venezuela and Iran.

It’s impossible to know what projections the Saudi leadership built their strategy around, but it appears their downside case was not that much more dire than that of conventional wisdom as of early 2015: that oil prices would be low for the first half of 2015, and would recover to more or less their former level in the second half of the year. One has to think the Saudis allowed for some overshoot in terms of what then would have been seen as a dire scenario, say oil below $60 for nine months.

In other words, the Saudis simply did not anticipate that both governments and private producers had the same incentives: to keep pumping because they needed the revenues so badly. And the deterioration of the Chinese economy and lousy fundamentals in Europe mean that low oil prices haven’t led to an upswing in consumption to offset the surplus supply.

The Saudis also underestimated the staying power of some of their opponents. US shale players would kept going as long as they had access to funding (and they also got adept about cost reduction, in cutting back at higher cost sites and increasing output at ones with better economics). And even though oil is an important export for Russia, it is far more diverse an economy than the one-trick-pony Saudi Arabia. Plus Putin played the nationalist card with military adventures in the Ukraine and Syria helping to maintain domestic support even as the Russian economy shrank.

So the severity and probable extended duration of low oil prices has blown back on Saudi Arabia in a very nasty way, particularly since its government and society have become very dependent on a high level of oil revenues. Russia and Iran are thus able to exploit the fact that the Saudis are being damaged by their own strategy and they won’t do an oil deal unless they also get a deal on Syria. That is something the Saudis will find very hard to swallow. But all that Russia and Iran have to do is stand pat, because they believe that it is the Saudis who are most vulnerable to protracted budgetary haemorrhaging. OPEC is divided and paralysed in the face of the collapse in oil prices. OPEC appears to be divided into two main camps: One has nine members — ranging from Algeria to Venezuela , who want to scrap the Saudi-led price war with non-OPEC producers. The problem for them is that the four who want to continue the fight, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE, hold nearly all of OPEC’s spare capacity, so their votes inevitably carry more sway. Also often overlooked is that OPEC only works by unanimous decision making the effort to corral all members incredibly difficult at a time when their economies are hurting badly.

To make matters worse Iran is about to re-join the economic world, with sanctions just set to be lifted as part of its nuclear deal with the West and at a minimum, this will place an additional 500,000 barrels per day back on the global market. With the US Congress now allowing oil exports, recently doing away with the 40-year prohibition of such sales, there seem to be few signs that the Saudi economic agony is about to end.

The impact of cheap oil on Saudi finances

Saudi Arabia has very low cost per barrel of production, much lower than any shale producer in the U.S. But as a country, Saudi Arabia also has other significant obligations that it has to meet and oil revenues are effectively its only way of meeting these obligations. The same principle holds true for all other OPEC producers, though most are in worse shape than the Saudis. With oil at these prices, all of OPEC is bleeding fast. The oil revenues that the Saudis and others are bringing in are simply not enough to meet their on-going obligations. As a result, Saudi Arabia and others have been forced to turn to their savings – foreign currency reserves.

In 2015, the Saudi budget deficit amounted to $98 billion, or a whopping 15 per cent of its GDP. While Riyadh has mountainous reserves, it needs the price of oil – the sole motor of its economy – to fetch around $100 a barrel to adequately finance public spending, a figure absolutely no one sees as remotely being on the horizon.

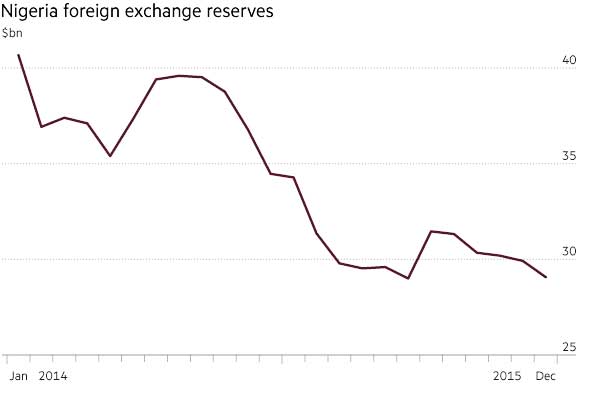

Saudi Arabia started 2015 with roughly $720B in reserves. By August it was down to $650B. As of December, Saudi Arabia has around $620B in reserves. If oil averages $20 a barrel going forward for the next couple of years, Saudi Arabia will be broke by mid-2018 even after accounting for its recent budget cuts that trimmed internal spending. $30 a barrel oil buys the country about 6 months, tiding it over to early 2019. Libya, Iraq, and Nigeria are all in much worse shape, as of course is Venezuela.

| Country | Estimated oil price required to balance 2015 budget |

|---|---|

| Norway | $40 |

| Kuwait | $54 |

| Abu Dhabi | $55 |

| Russia | $105 |

| Saudi Arabia | $106 |

| Nigeria | $122 |

| Iran | $131 |

| Algeria | $131 |

| Venezuela | $160 |

Even before Saudi Arabia gets to the point of bankruptcy though, panic may begin to set in for OPEC. Saudi Arabia is the most stable member of OPEC, and other than its rival Iran, who is used to budgetary pressure, the rest of OPEC is largely bloated and ill-prepared for a long period of low oil prices.

Saudi Arabia will likely end 2016 with around $450B in reserves, and other OPEC members will be in much worse shape. With reserves that low, many OPEC members may be forced to turn to the bond markets. Unfortunately for OPEC, the interest rate environment around the world is starting to tighten and bond rates will likely be higher by the end of this year. Add to that the continuing uncertainty around oil prices, and some countries may find bond market access very difficult. Even the Saudis may find that their financial strain is causing concern among bond investors.

There is reason to think that the price of oil will remain subdued for a long time to come if the Saudis have anything to say about the matter. In particular, the Kingdom is concerned about the rest of the world switching to other forms of energy sources, and sees low oil prices as a way to delay the adoption of substitute forms of energy.

But even the Saudis don’t want to see oil prices this low, nor can they afford a prolonged period of oil prices below $50 a barrel. To say that oil is crucial to Saudi Arabia is an understatement; oil is to Saudi Arabia what gambling is to Las Vegas. The Saudi’s cannot withstand low oil prices forever, and if drastic changes don’t happen, then within two years, the world’s largest oil producer maybe facing very hard times.

The broader impact of prolonged cheap oil

With the arrival of teams from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Azerbaijan this week, oil dependent economies across the developing world are facing the prospect of emergency bailouts after the collapse in the price of crude.

If Azerbaijan is the first to receive a bailout from the IMF and World Bank, as expected, the question analysts are asking is who comes next. Here are some of the countries that top their list of concerns.

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy and its biggest oil producer, is in a deepening crisis due to the fall in oil prices and to dwindling state coffers inherited from the previous government. Oil revenues account for more than 90 per cent of Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings and contingency planning is already under way as the Nigerian government and the World Bank have opened discussions on some $2bn-$3bn in budget support.

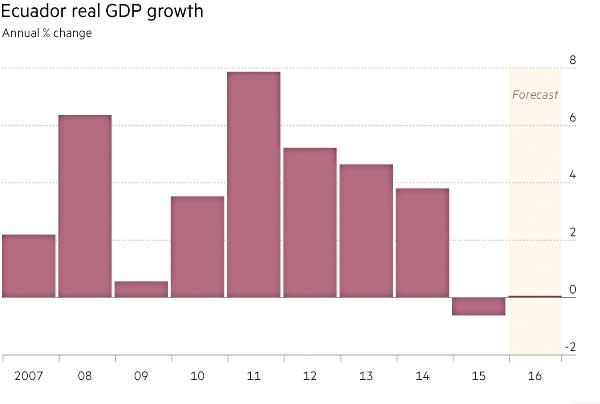

When Rafael Correa, Ecuador’s president, moved in December to pay off a bond falling due, he was eager to make the most of a landmark moment. For the first time since Ecuador first defaulted on a bond 183 years ago the oil-rich Andean nation was paying off a foreign debt. The move helped bolster investor confidence. But it also came against an ominous backdrop. As Mr Correa said at the time, the payment came “in a year when we have received zero in oil revenues”. Things have only gotten worse since then. Ecuador is among the countries cited most often by analysts when asked who might end up with an IMF programme this year. The reason is simple. As IMF staff laid out in an October paper, not only is Ecuador dependent on oil revenues but it also has a fully dollarised economy, meaning that its trade competitiveness is steadily being eroded as the dollar strengthens on the back of a recovery in the distant US.

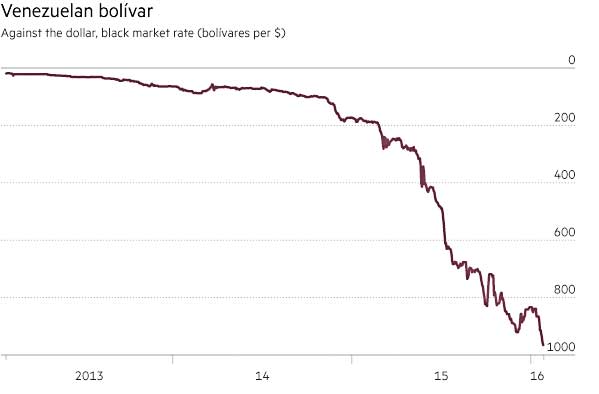

Venezuela is in a very difficult position because its oil dependent economy is essentially collapsing in free fall but Hugo Chávez built his rule on a narrative of socialist struggle against western imperialism and institutions like the IMF and World Bank. His successor, Nicolás Maduro, has done the same. But with a likely default on its debts looming Venezuela will almost certainly be forced to eventually turn to the IMF, a move that would be complicated by the fact the fund has not conducted a formal review of the Venezuelan economy since 2004. “Without a large IMF program [Venezuela would see] the largest output decline that you have seen in any country any time [recently],” says Ricardo Hausmann, a former Venezuelan planning minister who for months has been advocating an IMF program. “Venezuela is a catastrophe.”

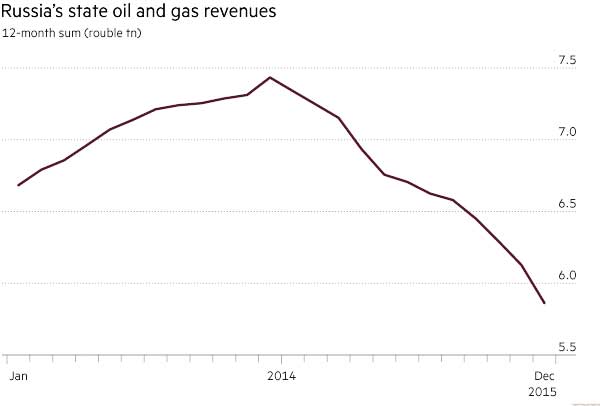

Russia and Kazakhstan the two largest former Soviet oil producers, have both been hit hard by the fall in prices. But both have substantial buffers that analysts say should protect them in the short term. However, their situation could become more uncomfortable if oil prices remain low. Russia is set to exhaust the rainy day fund designed to cover budget deficits within about 18 months. It also has limited access to external debt markets due to western sanctions against it. See my recent article looking in detail at the economic and political implications for Russia of low oil prices

In both Russia and Kazakhstan, currency falls mean the state is likely to be called in to provide further support to the banking sector and potentially other large companies with large US dollar external debts. However, while Russian oil producers are generally still profitable at current prices, Kazakh producers are under greater pressure. KazMunaiGas Exploration Production, the listed subsidiary of the state oil company, says its main production unit needs an oil price of $65 to break even.

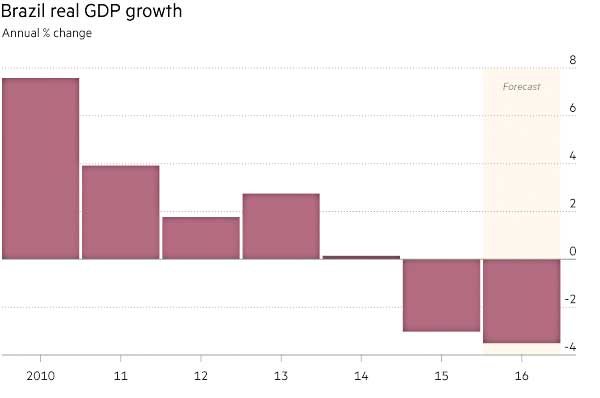

Brazil is facing a multitude of problems as its economy has fallen into a deep recession that is expected to drag on through this year, a political crisis over a corruption scandal in the oil industry that is fracturing the countries leadership and a currency that lost almost a third of its value against the US dollar in 2015. Brazil’s scandal-mired state oil producer, Petrobras, also has the ignominious honour of being the most indebted major oil company in the world. That has forced President Dilma Rousseff to start confronting publicly the possibility of her government having to bail out the oil company at what would be a huge cost to the public purse. Any IMF bailout of Brazil would be far larger than that offered to Greece, which is now by far the IMF’s biggest debtor. Moreover, the cost would likely have to be carried by the fund itself rather than shared, as has been the case with its recent rescue efforts in Europe.

Algeria’s economy is highly dependent on natural gas, and its foreign reserves dropped precipitously in 2015 because of lower oil export revenue, leading to a $10.8 billion deficit. A mild winter in Europe, a key market for Algerian natural gas, will not help the situation. Algeria has sought to boost foreign investment through tax reform and the introduction of import and export license authorisations. But the country is heading toward a precarious political moment: the eventual death of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who has held office since 1999. The nation’s elite are now jockeying for position ahead of this transition; although continued reform measures are necessary, many will be wary of any that may erode their power. This will limit the country’s options, compounding the current crisis

Iraq and Kurdistan

In Iraq, both Baghdad and the Kurdish capital of Arbil are already in serious financial trouble. At 143 billion barrels, plus an estimated undiscovered 215 billion barrels in oil reserves (excluding Kurdistan), Iraq is the 2nd biggest oil producer in OPEC after Saudi Arabia and has the 5th largest proven oil reserves. Oil exports contributed 47% of Iraqi GDP in 2013 alone, more than 90% of government revenue and over 99% of total exports. Overall, every single macroeconomic indicator has oil as its basis: both the current account and the foreign exchange reserves seem to track Brent crude prices. Nowhere will the collapse in prices hit Iraq harder than its budget revenues. With a budget so heavily dependent on oil (>90%) and with current spending representing 70% of total spending due to Iraq’s large public sector (5 million state employees, a third of the working population), the government does not have much flexibility. Government spending in Iraq has indeed been growing 14% on average every year since 2004. According to the International Energy Agency, the budget breakeven (the oil price that would be required for the budget to be balanced) is at around $105 per barrel.

Recognised as a federal entity by Baghdad, Kurdistan holds the world’s ninth-largest oil reserves and has many attributes of statehood, including effective control over its territory and its own armed forces. Kurdistan passed a law that allows it to raise funds through international borrowing and has mooted plans to raise $5 billion with an international bond issue this year. A deal struck in December under which Kurdistan is set to transfer crude to Iraqi state oil firm SOMO in exchange for Baghdad allocating Erbil budget payments has been in trouble from the start, with each side accusing the other of not sticking to the bargain. Proceeds from oil sales by SOMO are going through a U.S. account, which can only be drawn upon by the central government. Payments for Kurdish crude sold independently are collected in a Turkish state bank account, accessible to Erbil. In recent weeks, Kurdistan has ramped up sales through the Turkish port of Ceyhan, escalating tensions with Baghdad.

The national government and the Kurdistan Regional Government need to maintain high levels of spending to fund their battle against the Islamic State. With oil revenues dropping, this means they will need to reduce other expenditures.

The semi-autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq, an oil- producing region, has racked up $18 billion in debt, which has imperiled its ability to pay state workers and security forces. This is especially worrisome since Kurdish security forces have been instrumental in rolling back the Islamic State’s advances.

The drop in world oil prices and the strains of the war against the Islamic State have reversed the economic boom that had made the self-ruled Kurdish region of Iraq a rare success story in the troubled Middle East, threatening the Kurds’ role in the campaign to defeat the Islamist extremists. Two years ago, the three provinces of Iraqi Kurdistan were looking prosperous, with high rises transforming the skyline of its capital of Irbil and foreign investors jamming the city’s hotels. Now, grey concrete skeletons of half-built skyscrapers loom over unfinished roadways that cannot be completed until the regional government gets its finances in order. Foreigners are leaving and government employees haven’t been paid for months.

The Kurdish economy, struggling to cope with an influx of almost 1.8 million people fleeing the Islamic State, has been hit hard by a sharp drop in the price of oil, which has been trading at below $50 a barrel since mid-summer. The economic slowdown could eventually affect the Kurds’ ability to sustain a long military offensive against the jihadists. The Kurdish regional government is exporting more than 600,000 barrels of oil a day independent of Iraq’s federal government, angering the authorities in Baghdad. That’s helping offset funding shortfalls from Baghdad, which is supposed to forward 17 percent of the national budget to Kurdistan, according to the Kurdish Ministry of Natural Resources. But, according to The Associated Press, the Kurdish regional government has received only $2 billion of the roughly $18 billion to which it is entitled.

Scotland

When the SNP narrowly lost the independence referendum in in 2014, the price of a barrel of Brent oil was still over $100. AS the SNP has demolished the Scottish Labour Party there were some broad hints from the SNP that there could be a second referendum, sooner rather than later, especially if there was a vote for Brexit in the EU referendum.

The problem that the pro-independence camp now face is that the collapse in oil prices has fundamentally changed the economic arithmetic of independence. North Sea oil revenues, which have fluctuated over the last decade between £4-9.7 billion annually, or roughly between 7-17 per cent of total Scottish fiscal revenues. The negative consequences of low oil prices manifest themselves through lower petroleum revenue tax receipts, higher rebates claimed by North Sea oil companies, and of course lower revenues, profits and jobs in the industry, all of which, in turn, feed back into public tax revenues and outlays.

In the Scottish government’s last (June 2015) oil and gas bulletin, expected revenues were scaled back substantially. At the time of the referendum, and based on an oil price of $113 per barrel, oil revenues were expected to be almost £8 billion in 2016/17, and between $31-57 billion in the five years to 2017/18. These estimates were lowered to £500m-£2.8 billion, and £2.4 billion-£10.8 billion, respectively, the latter still based on oil prices rising back to $100.

Even these estimates look to have been overtaken by events. The Office for Budget Responsibility and the Institute of Fiscal Studies both reckoned in April last year that North Sea revenues would come in at around £600m-700m a year. The IFS estimated as a result that Scotland would run a budget deficit in 2015-16 of 8.6 per cent of GDP: the equivalent of a financing black hole of £7.6 billion, or a rise of roughly 23p on the basic rate of income tax. It predicted this chasm could rise to almost £10 billion by 2019/20. The OBR argued last November that North Sea revenues could even be as low as £130m in 2015/16 and £100m a year over the longer term.

Useful and informative as ever, Tony but one small query.

I get that Saudi lowered prices to see off competition via fracking and alternative energy sources but presumably if they had not, they would have had to reduce production or sales at least and so even with a higher price, their income from oil would have fallen to the benefit among others of the US? Thus the effect on their reserves would be similar

, no?(Of course, I care not for the fate of the horrendous Saudi government but trying to check the logic!)

Am I missing something?

Thats right, fracked oil coming online would through supply and demand tend to push oil prices down. I think the Saudis thought they could push up supply and thus push down oil prices even further, kill a lot of fracking investment, hit their geopolitical enemies economies, and then cut production to ease prices back up. But they lost control of the process. Fracking was far more price resilient than they thought, Iran did a a nuclear deal and returned to the global market, China slowed reducing demand and the China slow down also knocked commodity supplier economies into recession reducing their oil demand. So now the Saudis are stuck with a painfully low price for oil. Personally if I hope it bankrupts them as Saudi Arabia is both a ghastly country and also it plays a terribly reactionary role in spreading ghastly Wahhbabite ideology.

Comments on this entry are closed.