While we wait to see how the game of poker between Germany and Greece plays out here is some data to think about.

The Eurozone crisis has saved Germany a lot of money.

Ever since the creation of the Eurozone, and especially since the outbreak of the crisis in 2007, the interest rates that the German government has paid to borrow money has been steadily falling. Recently the banks have been so keen to buy German government bonds (Bunds) that the amount of interest that Germany has to offer in order to attract buyers has sometimes fallen below zero. People are willing to pay Germany to lend it money.

German officials are well aware of their stronger financing position, the result of a fall in borrowing costs, even as politicians continue to lament the risks being piled on German taxpayers.

When giving presentations in Germany, Klaus Regling, the German who heads the euro zone’s permanent bailout fund, often cites two studies that show that Berlin has reaped substantial savings as an unintended consequence of the crisis.

One study, by German insurance giant Allianz, has calculated that Berlin saved 10.2 billion euros in 2010-2012 because of lower borrowing costs, as yields on its 10-year bonds fell from 3.39 percent to 1.18 percent now.

The other study, by Jens Boysen-Hogrefe of the IfW economic institute, suggests that the German federal budget saved 8.6 billion euros in 2011 due to low ECB interest rates and the safe-haven impact of investors putting money into Germany.

Those savings rose to 9.6 billion in 2012 and the safe-haven effect will alone be worth 2 billion in 2013, IfW said.

“If we add up the interest rate advantages gained in the period 2010 to 2012 and those that Germany will benefit from in the years to come, we arrive at cumulative interest relief for the German budget of an estimated 67 billion euros,” Allianz said in a paper published last September.

“(That is) enough to slash around 3 percentage points off Germany’s government debt ratio,” which reaps further saving.

And it would cover any ‘losses’ from a Greek default.

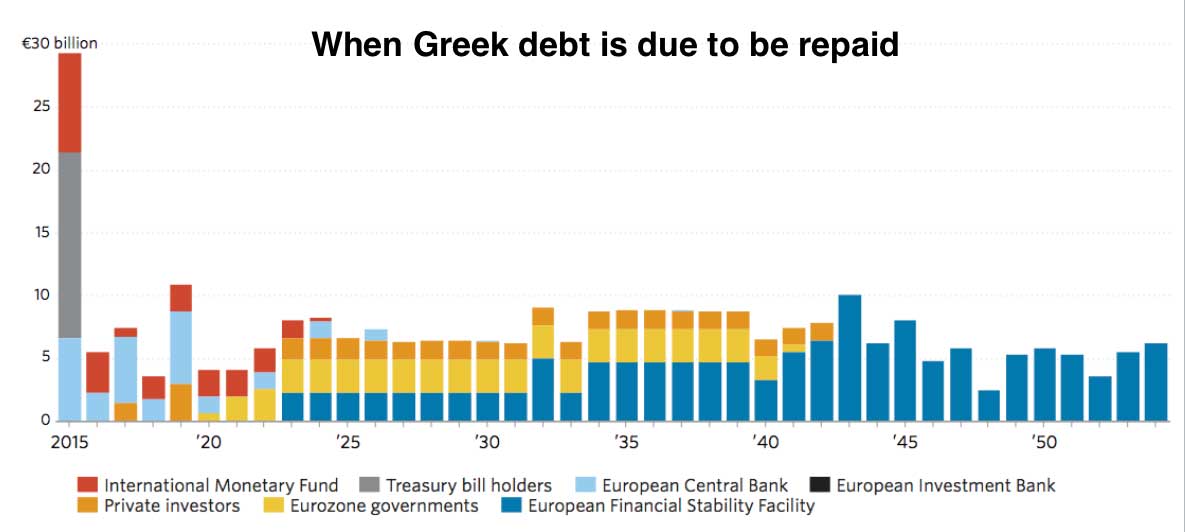

The Greek repayment schedule last until 2055

Here is a chart showing the current schedule of Greek debt repayments and which creditors will be repaid when. Notice how long this repayment schedule is, Greece is currently expected to generate a government surplus every year for the next forty years and then use it to repay its creditors.

Also note the really big payments coming due in 2015.

In a deep hole

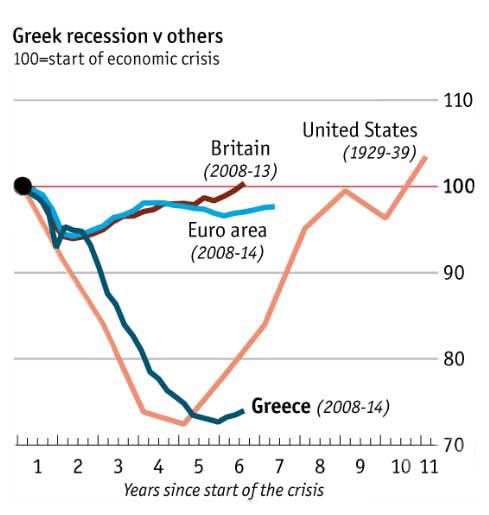

Since 2008, the Greek economy has shrunk by about a quarter which is almost as as deep a downturn as America’s Depression, however Greece’s recession is more more prolonged than the Great Depression and so far there has been no New Deal. Recent downturns in the euro area and Britain seem like minor hiccups in comparison.

Why digging deeper to get out of a hole is never a good idea.

Many Europeans are under the impression that their taxes have been funding Greeks’ pensions and salaries, when the truth is that only 11 percent of the 226.7 billion euros received by Athens has gone towards the government’s cash needs and covering the primary deficit, which no longer exists as of 2013. The Greek government is currently running a surplus, which given the scale of the collapse in the Greek economy is an astonishing achievement.

When Greece’s insolvency was clear, Kostas Karamanlis’s New Democracy government had left a public sector wage bill of 30.7 billion euros, almost 13 percent of GDP. In 2013, that same wage bill did not exceed 21.8 billion euros, representing a 29 percent reduction in just four years.

Social benefits in 2009 had risen to 49.1 billion euros from 36 billions in 2006. This was brought down to 38.4 billion in four years, a 27 percent reduction.

The task of balancing the Greek government budget was made much more difficult by the continuous reduction in revenues as people were losing jobs by the thousand each month. The Troika, in its wisdom, decided in 2012 to push down the Greek minimum wage by 22 percent as part of the internal devaluation process. This reduced wages in all collective agreements and enterprise level wage settlements which used the minimum wage as a benchmark. In turn, this sucked tax revenues and social insurance contributions out of the system. As a result social contributions dropped from 30.7 billion in 2008 to just 24.3 billion euros in 2013, down 21 percent. At the same time, taxes on income were reduced to 18.7 billions in 2013 from 20.2 in 2009 in spite of the repeated revenue-raising measures that the governments introduced.

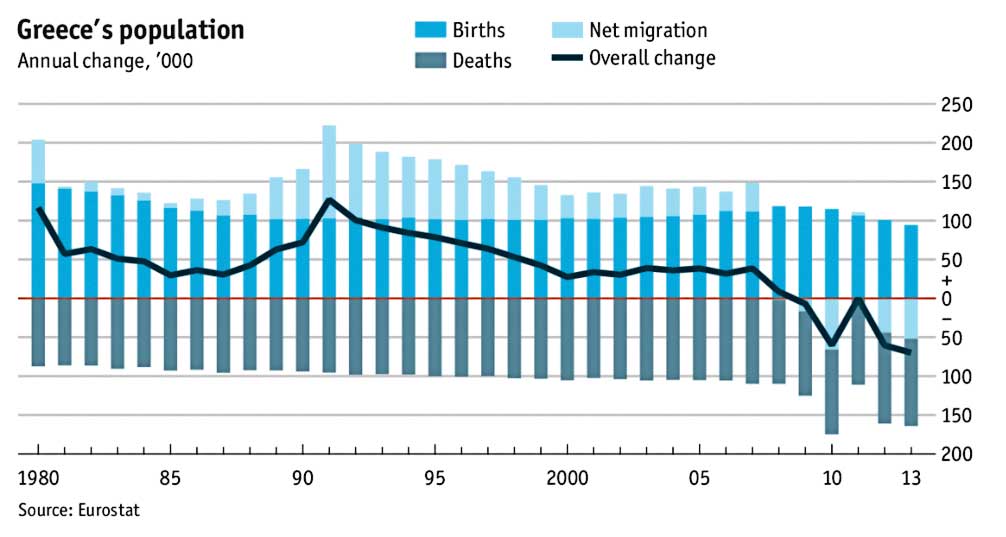

Depopulation is one possible solution to the ‘Greek problem’

In an amazingly prescient article in October 1992 in the London Review of Books the brilliant British economist Wynne Godley dissected the weaknesses of the proposed European Monetary Union system. He had this to say:

“What happens if a whole country – a potential ‘region’ in a fully integrated community – suffers a structural setback? So long as it is a sovereign state, it can devalue its currency. It can then trade successfully at full employment provided its people accept the necessary cut in their real incomes. With an economic and monetary union, this recourse is obviously barred, and its prospect is grave indeed unless federal budgeting arrangements are made which fulfil a redistributive role.

If a country or region has no power to devalue, and if it is not the beneficiary of a system of fiscal equalisation, then there is nothing to stop it suffering a process of cumulative and terminal decline leading, in the end, to emigration as the only alternative to poverty or starvation.”

This is what is happening to the Greek population. Its shrinking.