This is an extraordinary global and national crisis. I don’t think anything as big, complex or significant has happened since WWII. The collapse of the post war settlement and of the communist block in the 1980s and 1990s, and the rise of Chinese capitalism weren’t as big as this event. The next couple of years are going to be extraordinary and, assuming the epidemic fades after that (see below), the economic and social recovery is going to take years. Even when the epidemic is over and recovery is well underway the world will have been permanently changed, it will be very different but in ways we can’t fully foresee at this stage. The emergency measures now being deployed across the globe, which are on the same scale as the measures taken during WWII, will utterly change the way economies, international relations and political systems work. The world post epidemic will be a new sort of place. Unpicking what is happening now, let alone what it all means, is going to take years, so these are just a few very preliminary thoughts and pointers.

The epidemic

The best thing I have read about what to expect in the comings months, and how to understand the impact of government responses is this article: “Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance – What the Next 18 Months Can Look Like, if Leaders Buy Us Time” by Tomas Pueyo. The same author also wrote an earlier and equally informative article entitled “Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now”

There is also an interesting article entitled “The Doctor Who Helped Defeat Smallpox Explains What’s Coming” in Wired magazine

COVID-19 is now everywhere, spreading fast and the human race has no natural immunity. The epidemic will end when about 80% of humanity is immune, and that can come about either through the spread of the disease through the population or immunisation. Given that a vaccine is a year away in reality it will be a mixture of both, lots of people are going to get the virus and recover, and there will be a vaccination program eventually. This means that the lock down and social isolation that has brought the world’s economy to a juddering halt is probably going to go on for months, and if relaxed may have to be imposed again in a series of waves in response to the virus surging again. This means that in many countries, particularly in Europe, the USA and poor countries (especially Africa) health systems are going to be overwhelmed sometime over this summer.

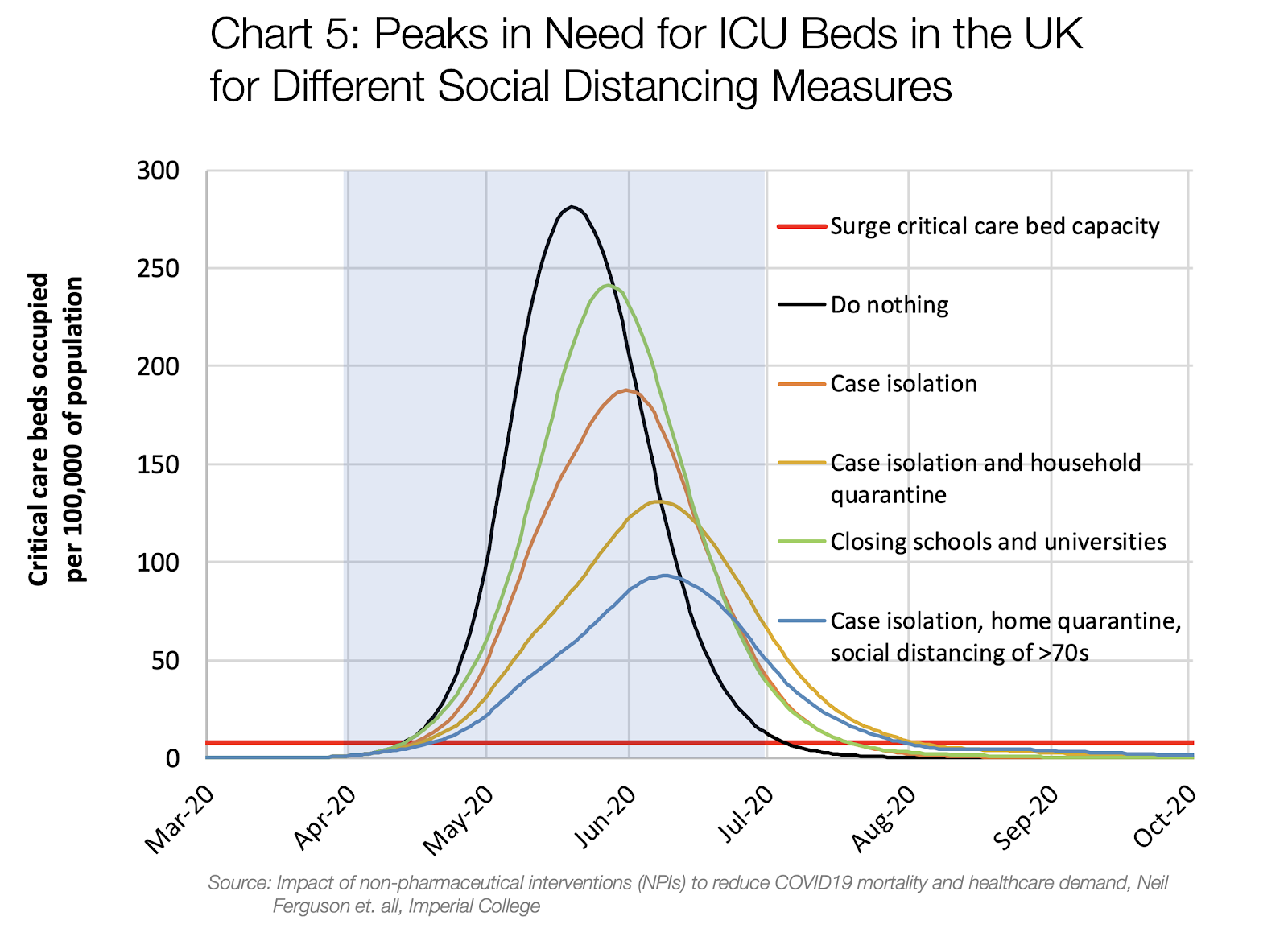

What to expect in the UK is shown in this rather frightening graph taken from the above article.

Economics

The global economy has just suffered a sudden stop on a massive scale. The economic impact of the epidemic is going to be as big as a major war, but on a global scale, everywhere, at the same time. The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) was caused by a sudden stop in the financial system that then rapidly led to a sharp contraction in parts of the global economy, although very important parts such as China helped to rapidly stabilise the real economy through a massive stimulas package.

This time, unlike GFC, the sudden stop has happened in demand (whole sectors such as cinemas, travel, car sales, restaurants, bars, hotels, etc have essentially collapsed), supply (many factories are closing, the entire European car industry has shut down), and there has been a sudden stop in the financial system (although different to the GFC it still involves a similar sudden drying up of dollar liquidity – see below). And it has happened everywhere.

The global economy in the decade since the GFC has seen slow growth, soaring debts levels and continuing weaknesses in some major banking sectors (in Europe in particular).The virus sudden stop came immediately on top of a global collapse in oil prices (unrelated to the virus) and hit a global system that had a series of acute weak spot.

These areas of pre-virus weakness included:

a) The looming end of the Chinese growth model. I have written before about the crisis of the Chinese growth model (see here and here) and why its investment led model was reaching the end of sustainability. Its limit of sustainability is expressed in debt levels growing faster than GDP growth and that gap was widening. Just prior to the virus emergency (in late 2019 and early 2020) an intense debate and political struggle was underway in the CCP leadership between those who wanted a new credit stimulus (and hence more debt and no restructuring of the growth model) and those who wanted to focus on debt management and reduction (and thus an acceptance of lower GDP growth rates). The virus means that debate is over and that there will now be a massive new credit stimulus (its already started) focussed on lots of new debt financed large scale infrastructural spending. This might work in the very short term but the need to move on, painfully, from an investment led model is even more pressing now, debt levels will surge to even higher levels, and the Chinese economy will find many of its external trading relationship disrupted by the global sudden stop. This time around it is far less likely that China can pull the global economy out of recession as it did in 2008. And the great unknown is how well will the rigidities of the Chinese political system, a system that has been made significantly more authoritarian under Xi Jinping in preparation for a growth model change, will cope with the political social stresses of slower growth.

b) After a brief reset after the GFC global debt levels have grown very significantly in the last decade. New problematic areas of debt have developed, in particular large scale corporate debt in the form of corporate bonds issued by companies that already could not redeem them even before the virus sudden stop. American Airlines have for example have issued tents of billions of bonds in order to fund stock buy-backs mostly to ensure the top management stock performance related bonus were paid and have now run out of cash and want a bail out from the US government. Many other big companies are already carrying large debts loads and have few cash reserves.

I was writing about global debt levels five years ago and it’s only got worse since then – see here

c) The continuing architectural weakness of the Euro system (no pooled fiscal system, incomplete banking resolution systems, no shared system of social spending), and it’s continuing institutional commitment to Ordoliberalism which blocked fiscal stimulus by the blocks strong economies, meant that the EU was already sliding from stagnation into recession even before the virus sudden stop. Italy pre-virus was already the main weak link in the Euro system, see here for more back ground).

See my article on the role of Ordoliberalism in the European Project

See my recent article about the eurozone Italian problem

d) A global economic system built around some very dangerous imbalances. In particular its dependence on the USA as both issuer of dollars which are the essential financial lubricant of the global economy, and via its trade deficit which means it acts as the world’s ‘consumer of last resort’. Now dollar liquidity is suffering a similar collapse as in 2008 and also as in 2008 the US Federal Reserve is scrambling to shore up global dollar liquidity via massive dollar swap lines. If as is likely the US economy suffers a significant contraction it will starve the world of demand just as the world economy enters a severe depression.

Adam Tooze has a very clear article about the financial situation the importance of dollar swap arrangements here

This Is the One Thing That Might Save the World From Financial Collapse

Note that the virus epidemic has hit, and is hitting, Europe, the US and China very hard so it’s economic impact is precisely on the weak spots outlined above

The shape of things to come

It’s impossible to know how exactly things will unfold in relation to the world economy and longer term political impacts, but it is most likely result will be not a just a global recession but a global depression. I have seen various projections for GDP loss in the coming year in the USA, the best was 10% (which under normal circumstances would be considered a catastrophe) and the worst was 25% which is simply apocalyptic. Yikes!!

The developed economy least well positioned to deal with the epidemic is the USA. Not only does it have an aggressively incompetent president but it’s entire (dysfunctional) system of federal government is poorly positioned to deal with this type of emergency and it’s ridiculous health system is acutely unsuitable for dealing with the medical impacts of the coming epidemic. Plus of course this is an election year and the only alternative too Trump seems to be an ageing Biden. Not a great choice. The US will eventually get on top of the epidemic but it will do so late, initially incompetently and it will probably trigger a national political and governance crisis, and many tens of thousands will die needlessly.

Meanwhile the global economy will violently contract unleashing unknown political tensions. At national levels there will be a war-time like massive extension of state intervention and control in the economy and in society in general, and a truly gigantic spending increase by most governments, much bigger than anything since WWII. How well the world coordinates the global economic response is nor clear yet but yet again this devilishly timed epidemic is occurring at a time when global economic coordination was already faltering.

How long the vastly increased role of the government will be required for is unclear but even if at a minimum it lasts a few months to a year, and it could go on longer than that, then when the epidemic abates the terrain of politics and governance will have been transformed. Just like the huge extension in state intervention that took place during WWII it won’t be possible to simply undo and roll back everything the government now takes on. In the post epidemic world I expect the UK government to be far more proactively involved in managing the welfare of lots of people, particularly groups that had been more or less abandoned previously.

When the epidemic abates governments everywhere will be carrying huge amounts of debt. How they deal with that will shape the post epidemic political terrain. The ex-the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury from 2005 to 2016 Nick Macpherson summed it up very well in a recent article “Our great institutions will help get Britain through this battle”

“There will be more intervention and more regulation in the weeks ahead. We are now in a war time economy where socialist dirigisme has a role unthinkable in peace time. Debate will be underway about increasing social security benefits – a way of better targeting “helicopter money”.

At times like this, it is easy to believe that the world is coming to an end. It isn’t. Britain has been through much worse. Britain has extraordinarily deep capital markets. It hasn’t defaulted since 1672.

The Treasury will already have one eye on the recovery: how to unwind the interventions and how to curtail the consequences of ever increasing government debt. Here, there are two models: the century of Gladstonian orthodoxy which followed the Napoleonic Wars, or the forty years of Keynesian inflation which paid for two world wars. The sensible Mr Sunak will seek to chart a middle way.”

One thing this crisis will do is eclipse climate alarm, certainly for a few years. Movements promoting acute climate alarm like Extinction Rebellion were building quite a lot of momentum before the epidemic but like so much else that has all shut down now. I cannot see that Cop26, the Glasgow climate change conference planned for the autumn, can take place and the days of assembling tens of thousands of delegates to conferences like that may be over. When the world enters its post epidemic economic recovery phase it will not be prioritising expensive Green New Deals no matter how much green activists campaign for them, the priority is going to be restarting fast economic growth, ensuring cheap energy supplies and restarting world trade. In my opinion pausing the rush towards radical decarbonisation is no bad thing. How best to adjust to climate change in a way that delivers maximum human welfare, which should surely be the goal of any progressive rational humanist, is a complex issue. Rapid and deep decarbonisation always seemed to me probably undeliverable and certainly undesirable. We need a complex mix of policies around climate change and the years ahead, when climate change recedes to a background issue, will give us the space to work out more sophisticated responses than the simplicities of green slogans.