In a recent article in the Independent Chuka Umunna, Labour’s spokesman on business, innovation and skills, had this to say:

“In 2007, before the crisis hit, the UK government was running a deficit. By historical standards, it was small and uncontroversial – it averaged 1.3 per cent from 1997 to 2007, compared with 3.2 per cent beforehand under 18 years of Tory rule. And yet to be running a deficit in 2007, after 15 years of economic growth, was still a mistake.“

and then he added this:

“Our goal now must be to show that we have learned the lessons from this past. We must now go about doing this ruthlessly if we are to regain trust. It starts by asserting again and again that reducing the deficit is a progressive endeavour – we seek to balance the books because it is the right thing to do. We will not stand by while the state spends more paying interest every year to City speculators and investors holding government debt, than we do on people’s housing, skills or transport.”

What Umunna is saying here is essentially the same as George Osborne’s proposed surplus rule, that in normal times when the economy is growing the government should always run surpluses. But Osborne is saying that in the context of the current debt to GDP ratio of 80% of GDP. Umunna is implying that policy still made sense back in 2007 when the debt to GDP ratio was below 40%, the output gap was thought to be small and no one was expecting a global financial crisis. I cannot remember anyone before 2008 suggesting Labour’s debt limit should fall over time. Yet Umunna is making the ridiculous claim that the mistake was so serious that it helped lose Labour two elections.

These remarks by Umunna reveal a profound lack of understanding about how the national economy works. It reveals that Umunna, and I fear most of the rest of the Labour leadership, have swallowed hook, line and sinker a deeply fallacious and superficial notion of how the UK national economy works, and that they believe, completely wrongly, that large national economies can be best understood using the ideas, concepts and metaphors taken from the management of household or business finances. This is a profound intellectual and strategic error, one that compounds the grave error made when the post Brown leadership decided not to defend the spending record of the last Labour Government.

The Tories talking bollocks about the deficit is understandable, they want to use the deficit as an excuse to shrink the state, but there is no justification for Labour to spout such nonsense and doing so merely incapacitates them politically.

George Osborne’s has proposed to legislate for a mandatory budget surplus during “normal” economic conditions and this has predictably provoked some in a Labour Party still reeling in a state of post defeat disorientation to blurt out daft ‘me too’ semi endorsements of Osborne’s silly proposal. The Labour Party remains dreadfully constrained by the long term consequences of the disastrous decision by all the candidates in the 2010 Labour leadership election to distant themselves from the New Labour legacy by refusing to defend the spending program of the previous Labour government.

In the period between the crash of 2007-2008 and into the period immediately after the election of 2010 the Labour party should have been totally focussed on getting across a simple message: Labour did not overspend, the banks behaved in a criminally reckless fashion and nearly bankrupted the country, we had to use a lot of public money to prevent a collapse of the financial system, it has costs us dearly.

If Labour could have won the battle about how to define the problem with that message it could have opened the way to win the argument on how the solution was constructed with another simple message: the result of the necessary, but very costly, bail out of the banks is that the government’s debts have gone up, but the UK has very good credit ratings so we don’t need to panic, we must fix the financial system, punish the bad bankers and start the economy growing again which will over time fix the deficit.

Tragically that message, placing the blame for the surge in government debt correctly on the financial crisis and the resulting recession, was not made and as a result the alternative discourse has triumphed: Labour overspent because they are too incompetent to run the economy and now the Tories have to clean up the mess by balancing the books and paying off the debts.

It can be argued that political parties have won and lost power for extended periods of time in the UK based almost solely on their reputation for economic competence whilst in government. Once a party in power loses its reputation for economic competency and is cast into opposition it finds it hard to recover trust in its abilities and to displace an incumbent party until the incumbent party in turn loses its reputation for economic competency. Labour lost its reputation for economic competency during the late 1970s and was out of power until the Tories in turn lost their reputation for economic competency as a result of Black Wednesday in 1992. After that shambolic disaster the Tory party could not recover, the administration of John Major were just dead men walking, and the Tories did not recover until Labour in turn lost its reputation for competency in the lead up to the 2010 election. As a result Labour may be out of power until this current Tory administration also loses its reputation for economic competency.

So what are the outlooks for the government deficit and the UK economy as a whole? Is the recent growth and recovery sustainable? What determines the size of the government deficit and how much can a government control it?

Thinking about the deficit the wrong way

It is critically important that the Labour Party restores a degree of economic credibility but it will be tough. The task will be harder if the party is seduced into supporting nonsensical and economically illiterate ideas about how the UK economy works, about how to reduce the deficit and about defining what the real economic issues are. The confusion of the Labour Party is not helped by a general confusion amongst almost all politicians and commentators about the right way to think about the UK economy, or indeed any economy.

The seductive and persistent error that many commentators fall into, including a lot of economists and almost all politicians, is to think that the way the UK economy works is pretty much like the way the finances of an individual, household or firm work. This mistaken view, that the economy of an entire country can be understood using the same principles as are used to understand and manage individual finances, is not helped by the fact that most economists now specialise in the branch of economics that analyses the market behaviour of individual consumers and firms, and that microeconomics is the dominant analytical framework within academia and amongst economic commentators. As a result, in discussing the economy as a whole, many economists tend to draw macroeconomic conclusions from microeconomic reasoning and like George Osborne they discuss the government’s finances as if the government can be compared to a household.

This has confused the electorate (not to mention politicians) which rightly believes that households should in general “live within their means”, “balance their budgets” and “eliminate their deficits” and that these same principle can just be scaled up to map out what is prudent or sensible policy for the entire national economy. This belief that the entire economy, just like individual households, must be balance its budget and not fall into debt has perversely not stopped the Tories from strongly promoting house ownership which involves individual households going massively into debt in order to make a long term investment in property.

One of the results of thinking about the national UK economy as if it were an individual household or firm is that there is a mistaken belief that what determines the budget balance of the government, the surplus or deficit, is actually under the control of the government. It is not. The government cannot simply reduce spending and as a consequence reduce the deficit because the budget balance is actually the outcome of the performance of the economy as a whole – which is something the government cannot control (although it can influence it).

The budget deficit is an outcome of decisions made by both the private and public sectors to expand or contract activity, of the resulting levels of both public and private employment, and of the amount collected in tax revenues. When economic activity expands tax revenues increase and spending on unemployment benefits and social welfare falls, so an expanding or growing economy working near capacity reduces the deficit and improves government finances. Conversely a weak economy, operating below capacity, weakens government finances because tax revenues fall and spending on social welfare increases.

While the Chancellor can’t “eliminate the deficit” he can cut government expenditure and investment, or increase government expenditure and investment, and this can effect the general level of activity in the economy as a whole. An expansionary fiscal policy can lead to growth in activity and employment so that, in a recession, public sector expenditure and investment creates employment, generates tax revenues, saves on benefits and welfare payments and thereby reduces the deficit. A policy of fiscal consolidation or contraction, at a time when the private sector is in a slump, suffering from an overhang of debt, weak productivity, a lack of confidence and is hoarding cash and withholding investment, will cause the deficit to rise. In other words, it is not possible to assess the stance of the Chancellor’s fiscal policy from estimates of the public sector deficit – the planned budget outcome – but must include the likely impact of government fiscal policy on the levels of activity in the economy as a whole which in turn greatly influence government income and expenditure.

So the debate is not between those who would “slash the deficit” and those who would “postpone” the reduction in the deficit. Instead the debate is between those who would cut expenditure and investment in a slump, as opposed to those who would stimulate public expenditure and investment at times of private sector weakness. Bear in mind that the cost of government borrowing is at the moment at almost record lows so this would be an ideal time for the government to undertake a sensible investment programme using borrowed funds.

The Tories want to cut public expenditure for idealogical reason, because they think a smaller state would be a good thing in general but they do, partially, understand how austerity contracts the economy which is why the austerity relaxed halfway through the last parliament and that is the reason why UK growth picked up. The government’s June 2010 projections forecast that the budget would be balanced by 2014/15, the fiscal year just gone. But that was not to be. Despite substantial cuts to government spending, the Office of Budget Responsibility’s March 2015 outlook put the 2014-15 deficit at 3.3% of GDP. That’s a lot of red ink. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects the deficit to be about £75 billion in 2015-16 in total, or £46 billion excluding investment borrowing.

Worse still contrary to Mr Osborne’s fervent hopes and promises, the OBR expects UK public sector net debt to peak relative to the size of the economy in 2014-15 at 80.4% of national income, the highest ratio since the late 1960s. Its worth noting that the OBR calculates that net government debt prior to the slump that followed the financial crisis, a period which the Tories have succeeded in portraying as a period of huge and unsustainable Labour profligacy, the national debt was only 40 per cent of national income.

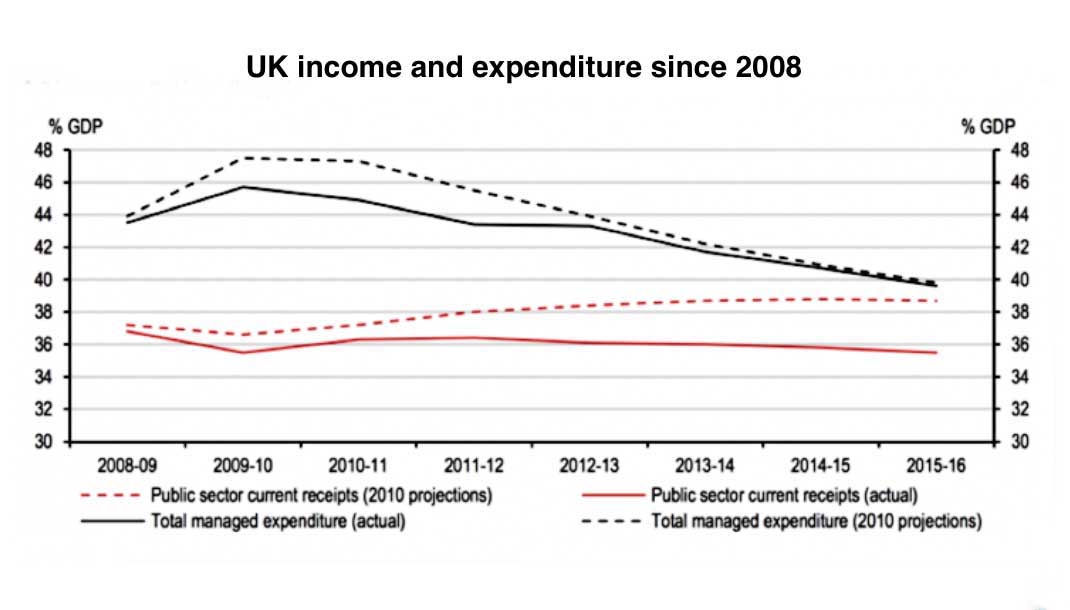

This chart shows why Osborne failed to “slash the deficit.” He cut spending and public investment, and the outcome was that tax revenues fell, and the deficit rose. The dotted red line shows what Mr Osborne expected would happen to tax receipts if he cut government spending. The red line shows what actually happened.

If Labour is to regain trust on economic policy it must do so on the basis of how the economy actually works and not allows itself to be drawn onto the terrain of fantasy economics where everything is explained as if the finances of the national economy behaves like the finances of a private household or individual firm. This will be difficult and will require great persistence and clarity because the common sense that the average voter applies to the issue of budgets and deficits is completely wrong and so a counter narrative is for most voters counter intuitive. That’s why Labour must reach out to and work with those economists who work within a correct macroeconomic framework, they may be in a minority within their profession but there are plenty of them and they can add considerable weight to the difficult arguments that Labour must put forward.

What is the real condition of the UK economy?

With GDP growth in the UK back above 2.5 per cent, economic recovery is widely regarded as being finally back on course. UK GDP growth is currently higher than that of any other large European nation. Last year, real GDP finally exceeded its pre-crisis peak. So are the problems of the UK economy over? The short answer is no. The recent upturn in GDP was the result initially of the relaxation in spending cuts by the government and now the impetus for the continuing growth is the recovery in consumption demand, which is in turn significantly underpinned by resurgence in the expansion of credit to households. Its the rising levels of personal debts that is fuelling growth and if the projections generated by the Cambridge Alphametrics macro-economic policy model (CAM) are correct this growth strategy cannot be sustained (see details below).

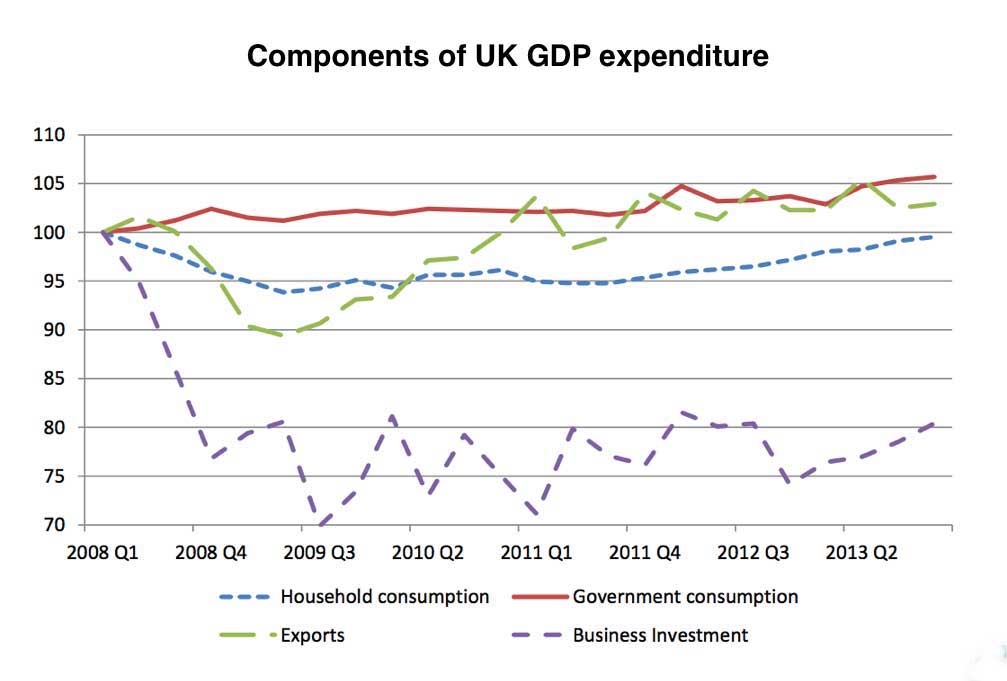

In UK Chancellor George Osborne’s 2014 budget speech, he claimed, “We’re putting Britain right.” It is hard to reconcile this claim with the macroeconomic data. In a more illuminating comment, he noted that the British “still don’t invest enough, export enough or save enough.” This is confirmed by the chart below, which shows the main expenditure components of UK GDP (rebased to a common index at the first quarter of 2008). By late 2009, the volume of business investment had fallen by nearly a third and, despite a recovery during 2013, is still twenty per cent below pre-crisis levels. Over the same period, household consumption fell by only around five per cent and has since recovered to almost pre-crisis levels. Exports are slightly up on 2008 levels, but this improvement is much weaker than might have been expected, given the substantial devaluation of the pound that has taken place. The spectacular collapse in investment since the start of the 2008 crisis is part of a longer-term trend of falling investment in the United Kingdom: private investment peaked at 19 per cent of GDP in 1989 before falling to a low of 12 percent of GDP in 2011.

When an economy contracts, as the UK economy did after the financial crash of 2008, it does so because it is rebalancing at below capacity. In a balanced economy consumption plus investment equals total production, and investment equals total savings. If production, consumption, investment and savings are all balanced at maximum capacity the economy will grow and unemployment will fall, and conversely if they are balanced at less than maximum capacity unemployment will rise and the economy will contract. Before examining in a bit more detail what this means for the economic outlook in the UK it would be useful for readers to have a look at the article here which explains how large-scale balances in a national economy work.

Prior to 2008 in the UK (and indeed across the economies of the USA and the eurozone periphery) the result of global imbalances meant that much of the growth and employment in the economy was the result of debt fuelled consumption and the inflation of debt fuelled asset bubbles. When the crisis came and the flow of credit contracted economies all across the globe including the UK economy contracted.

The recovery since the crash of 2008 has not been the result of recovery of investment levels but has been based upon the growth of credit fuelled consumption and the continuing inflation of the property market. That is not a sustainable basis for growth in the medium to long term. Under such circumstances, stagnation can only be avoided in one of three ways: by running a significant net export surplus; through government deficit spending; or through the extension of credit to the private sector in order to maintain consumption demand. Over the past few decades, the UK has repeatedly chosen the final option of reliance on private debt led aggregate demand and it was the sudden contraction in the credit that up until then had fuelled debt based consumption that largely caused the post 2008 contraction (despite the current government’s highly misleading yet endlessly repeated claims that excessive government spending was at fault).

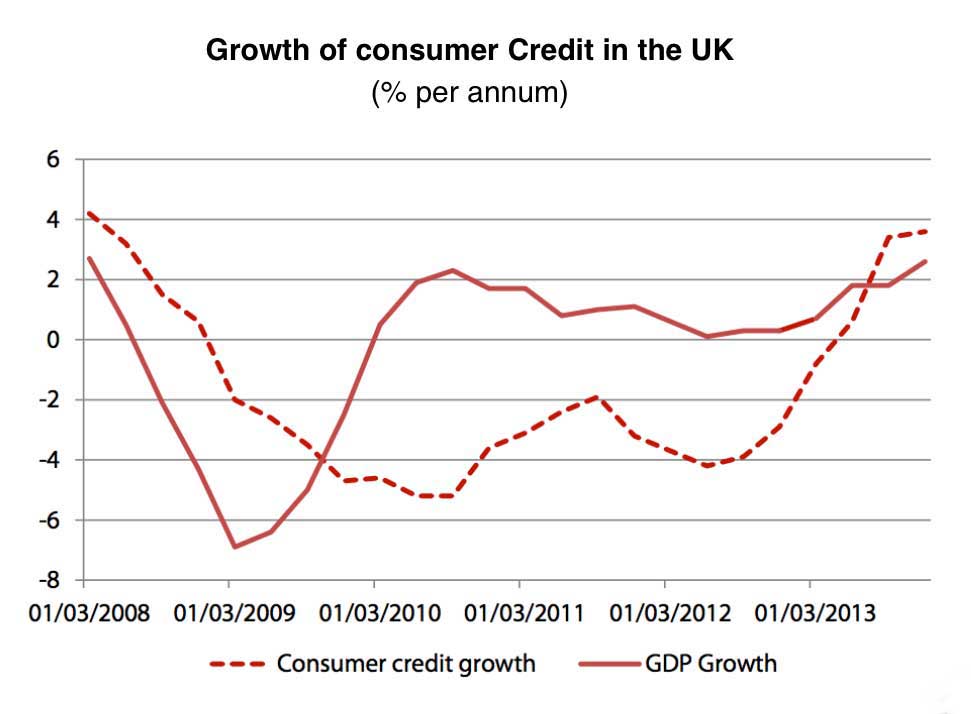

It is a return to the debt-led and consumption-driven growth path of the pre-crisis era that explains the recent improvement in UK GDP growth figures. This is illustrated in the chart below which shows annualised growth rates of real GDP and consumer credit. Alongside the return to growth that took place during 2013 was also a dramatic turnaround in the trend of the deleveraging of the household sector, that means that people stopped paying off personal debts and started accumulating more debt. While in the autumn of 2012, consumer credit was still contracting at a rate of around four per cent annually, only one year later credit expansion had resumed, with positive credit growth of close to four per cent per annum. The ratio of UK household debt to disposable income peaked at 164 per cent in 2010, and has since declined to just over 140 per cent but this trend towards a smaller personal debt level will soon go into reverse if the government continues to rely on debt-driven consumer spending in order to maintain growth rates.

The University of the West of England has produced a series of projections using the CAM model examining a scenario, based on current government policies, in which austerity measures are maintained, in a continued attempt to reduce the government deficit. At the same time, it is assumed that sustained growth of around 2 per cent per annum on average over the period 2014 to 2020 is achieved through rising consumption expenditures, while private investment remains at historically low levels of below 14 percent of GDP. The projected outcomes of such a scenario are shown in table below

| CAM Actuals and projections for the UK based on continued debt led growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption as % of GDP | Private Sector Net Lending | Current Account | |

| 2001-2004 | 66 | 1.2 | -0.9 |

| 2005-2008 | 64 | 1.7 | -1.8 |

| 2009-2012 | 64 | 6.6 | -2.7 |

| 2013-2016 | 67 | 0.9 | -6.3 |

| 2017-2020 | 69 | -4.2 | -7.5 |

According to this projection, in order to maintain average growth of around 2 per cent per annum over the next seven years under conditions of government austerity and weak private investment, the share of consumption in GDP would have to rise to a record 69 per cent by 2020. At the same time, the net financial deficit of the private sector would exceed four per cent of GDP and the current account deficit would exceed seven per cent.

When considering what the implications of maintaining personal debt based growth until 2020 might mean it is worth recalling the famous warning issued by Wynne Godley in 1999 regarding the then debt-led trajectory of the US economy:

“Moreover, if the growth in net lending … were to continue for another eight years, the implied indebtedness of the private sector would then be so extremely large that a sensational day of reckoning could then be at hand.” Source.

The financial crisis erupted eights years after these remarks by Wynne Godley

Godley concluded that “the present stance of policy is fundamentally out of kilter and will eventally have to be changed radically.” These words may well prove prescient in relation to the UK and current government strategy which is reproducing and reinforcing exactly the same sorts of imbalances which proved so deadly in 2008. The reliance of the Tory government on the indebtedness of the household sector to maintain GDP growth rates is fundamentally unsustainable. One way or another, the current growth trajectory will come to an end, the issue is what happens then.

It is impossible to know when the current Tory economic strategy will unravel or how deftly or how poorly the Tories will manage that process. What is crystal clear is that if the best the Labour Party can come up with is the aping of precisely the same economically illiterate posturing about deficit reduction that the Tories are peddling, and especially if the Labour Party does not develop its own robust economic analysis and set of policy propositions that address the real and deep seated problems of the UK economy, then Labour will not be able to take advantage of the economic failures of this government. Which means that even if economy shifts back into crisis mode and growth stagnates the Tories might be deft enough to survive if they are only faced with an enfeebled opposition which is intellectually incapable of proposing a clear and plausible alternative.

As you say, the Tories dont really have an interest in looking after all the people of Britain, only those that matter to them and so feel able to carry on austerity politics for ideological rather than economically sound reasons without any feelings of remorse. All those that suffer from the Tory ideology of shrinking government, the vulnerable, poor, low paid, homeless, unemployed, immigrants are instead demonised so that they wont be seen as proof of their broken economic policy and unfortunately people swallow the lie.

Margaret Thatcher perhaps encouraged this with her “no society” remarks: “I think we have gone through a period when too many children and people have been given to understand “I have a problem, it is the Government’s job to cope with it!” or “I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!” “I am homeless, the Government must house me!” and so they are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families and no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first… There is no such thing as society. There is living tapestry of men and women and people and the beauty of that tapestry and the quality of our lives will depend upon how much each of us is prepared to take responsibility for ourselves and each of us prepared to turn round and help by our own efforts those who are unfortunate.’

There could be truth in some small part of this which is why it is so dangerous and pernicious. It would be great if people were sensitised to live by the philosophy of helping others by their own will and effort as after all, all religions espouse this sentiment. Unfortunately Cameron’s version, the Big Society and Small Government which speaks of a society with much higher levels of personal, professional, civic and corporate responsibility; a society where people come together to solve problems and improve life for themselves and their communities; a society where the leading force for progress is social responsibility, not state control is really a con and some parts of society are allowed special dispensation to run amok like bankers, speculators and developers.

Comments on this entry are closed.