Who has the UK been negotiating with? The Brexit ‘negotiating’ process since Article 50 was triggered has been described and analysed as a negotiation between the UK and something called the EU, but what is this EU? The EU does not have a political centre, or an explicitly hegemonic member state, it is not an empire and there is no imperial power centre. Ever since the Article 50 process was triggered the UK has been negotiating with no one.

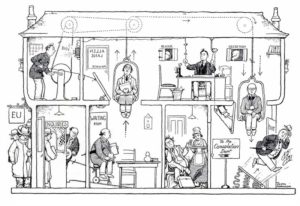

The EU is a complex layer of institutions, bureaucracies, technocrats and elites that have been built on top of a very complex and permanent system of (almost exclusively secret) diplomacy. The result of this institutionalised and permanent diplomatic engagement is a complex series of interlocking agreements and rules which have been accumulated over time and which are codified in a series of treaties and a very large number of regulations all written up in the form of ‘laws’ policed by a supranational legal system and a special purpose Supreme Court.

In many ways the EU is an entirely new, unusual and unique political system. It does not operate, and cannot operate, like a normal partner in an international negotiation. The EU can of course engage with external entities and negotiate arrangements, especially in relation to trade and commerce, but it can not do so quickly, adroitly or with agility. It’s own byzantine diplomatic foundations preclude this. All formalised external EU agreements and treaties have to be painstakingly crafted step by step with constant testing and referrals back to the EU’s own dense political system of internal treaties and it’s complex system of rules by which it functions and by which it governs itself. The default bottom line for external EU negotiations is that any external agreement must not disturb or undermine it’s own internal system of delicately codified and institutionalised diplomatic agreements.

Although the EU system can seem substantial and solid, especially when viewed from the outside, those functionaries that operate its systems are all too aware of how difficult it is to secure, maintain, implement and protect the raft of interlocking diplomatic clauses that make up it’s substance. Such a system does not respond well to external shocks or sudden crises. It is a system that is designed to work slowly in a protracted process of consensus building and diplomacy, a system that can – just about – move forward one plodding step at a time. Up until the Lisbon Treaty of 2007 the EU system had also managed to occasionally take bigger steps forward, always towards a loosely defined future of ‘ever greater union’, via sporadic large scale treaties. But Lisbon seems to have been the moment when that process, which had begun with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, came to an exhausted stop. No new treaties or big steps seem likely in the near future, there is nothing big in the diplomatic pipeline, and so what is left is a constant fine tuning of what has been achieved to date.

The problem for the EU is that the entire process, from Maastricht to Lisbon, has built a system that works but which is no longer capable of dynamism or continuing substantial evolution. That’s its current state, but it is possible of course that major political developments, crises and events might once again energise it and restart a more substantial evolutionary period but the need to protect and conserve what has already been achieved actually mitigates against such developments. The most powerful parts of the EU system, such as Coreper (see here for a detailed analysis of how the political system of the EU actually works), are precisely the parts least inclined to engage in any further major tinkering with the currently functioning, and momentarily stable, Heath Robinson construction lest it become destabilised. One only has to look at the abysmal, chaotic and absurdly counterproductive way in which the EU system responded to the first crises of the Euro in 2010 to see how ill-suited the current EU system is to dealing with fast moving internal crises and events.

So when the EU was confronted by the Brexit referendum result it absolutely could not respond as a hegemonic power should, or indeed with any sort of overarching strategic vision. It could not do so because it’s internal system has no centre and thus cannot construct a single vision backed with political power that would be needed to deal with an event such as Brexit. In addition the functionaries of the EU know that the deep fractures revealed in the UK by the referendum reflects similar tensions that have been building all across the Union. These tension are obviously a result of the weaknesses of the current EU architecture but because any further major architectural innovations are off the table the only response can be a defensive one which seeks to protect and preserve a status quo that has been painstakingly assembled over so many decades.

If there were an hegemonic centre to the EU, and if the system upon which it sat was robust enough (as robust as, say, a nation state) then clearly the response to the UK leaving would be a strategic one that would seek to negotiate a mutually beneficial new relationship, one that would seek to conserve as much economic, security, political and technical collaboration as possible. Given the UK’s status as the world’s sixth largest economy, one of the most important consumers of the EU’s trade surplus, one of the only two major military powers in Europe capable of actually fighting wars, a world leader in security and intelligence with privileged working arrangements with the US security system, and the location of by far the most important financial centre in Europe, any hegemonic political centre in the EU would be willing to be flexible in order to avoid a rupture. But no such centre exists. Only Angela Merkel could have masqueraded as a pale imitation of a hegemonic leader in this process and she suffered a terminal collapse of political authority just as the Brexit process started.

The response of the actual EU system is predictably to defend the inviolability of the current internal EU arrangements and rules, and to press the UK to fit into those rules in some way. Or live outside them. What can not be considered in any way, not least because there is no system or apparatus in the EU that could do such considering, is the possibility that the EU system itself might be adapted in order to accommodate a new sort of close working partnership with a big new independent neighbour and old friend. The EU system is not strong or stable enough to be tinkered with in order to accommodate a new sort of relationship with the UK and anyway who would do such tinkering?

So when Michel Barnier sits across the table from the UK he is not there to negotiate, he is there to communicate the needs of the EU system and to press for the UK’s compliance with that system. He has no power, no mandate and none of the institutional of political backing that would be required to negotiate a new relationship with the UK. If the UK were to make a proposal that would require a change in the way the EU does things who does Barnier call? The Commission, the heads and foreign ministries of 27 member states, the European Parliament? Before he could get an answer the Brexit timetable would have long run out of time.

The UK has consistently failed to recognise that no negotiations were actually taking place and as result the two sides have constantly talked past each other. As time has ran out (and who in their right mind would impose a timetable, least of all such a short timetable on such a process) the UK is finally confronting the choice its has always had since agreeing to the EU’s demands about the timetable of talks and the budget deal: either continued integration with the EU system with no rights of consultation or representation in its operation, or, hard ejection even though that would mean very high costs for both sides.