Although the Brexit vote has been met with a wave of despair and panic what will actually happen is still very unclear and will remain unclear for several months, and possibly years. The referendum vote was an advisory vote. All that has happened is that the the electorate has by a small but clear majority said it wants the UK to leave the EU. It is now up to the UK government to decide how best to act upon that referendum outcome. In other words it is now all a matter of politics.

Its look like the referendum has been the final straw for the Labour Party and it appears to be spiralling towards disintegration. It is very likely that it will be unable to act as a coherent opposition in the next few months, or contribute much to constructing a post referendum deal. The rest of the EU, the other governments (particularly the big players) and the various EU institutions can huff and puff all they want but the initiative is now with the UK. Only the UK can trigger Article 50 and start the formal divorce proceedings. There have been many statements from the EU saying no to informal negotiations prior to an Article 50 declaration but this is a game of bluff and counter bluff with a great deal at stake. No German or French leader is going to not answer the phone when the new UK prime minister calls, neither will they refuse to meet them, and when they talk the issue of Brexit is inevitably going to be discussed. There will be informal negotiations in all but name.

All we need now is a functioning UK government.

The harsh realities of Brexit

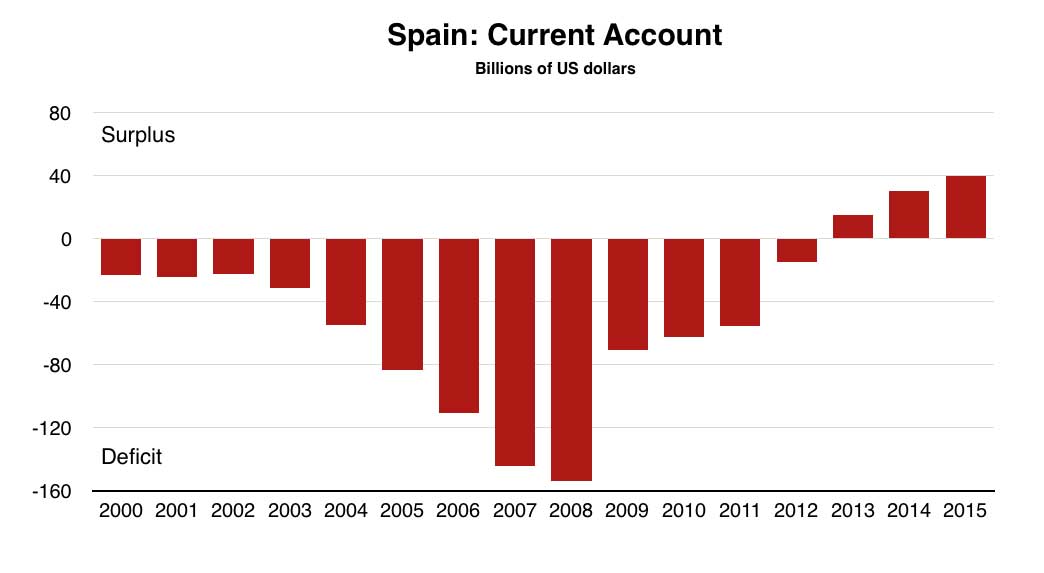

Much has been said in recent days about the cost of Brexit for the UK but there is a huge amount at stake for the EU. Remember that the eurozone is suffering from a chronic lack of demand, hence its stagnation and high unemployment. The flawed architecture of the eurozone means that some countries can continue to run massive trade surpluses while deficit countries are punished and ‘adjusted’ by having their internal economies deflated. It is the German model that is being imposed on the rest of the eurozone and that model is built on suppressing internal demand (by suppressing wages, domestic consumption, and domestic investment) and importing demand from abroad by running a huge trade surplus. The only source of growth of demand in the EU now is external demand, the only way eurozone countries can maintain their economies is by suppressing internal demand and running trade surpluses. But the imported demand is not enough to run the eurozone at full capacity and the result is stagnant growth and high unemployment. So the last thing the eurozone needs is to lose a significant source of external demand and that is exactly what it will do if a Brexit deal severely disrupts trade with the UK.

The UK has been supporting the US in playing the role of consumers of last resort. It is the huge trade deficits of the US and the UK that have balanced the huge trade surpluses of China, Germany (and now the rest of eurozone as a whole) and Japan. Without the trade deficits of the US and the UK the global economy would sharply deflate and contract.

These sorts of global imbalances, some countries running persistent big surpluses others running persistent large deficits, are not healthy, they lead to destabilising capital flows and, inevitably, to asset bubbles and debt crisis. But while they are running they do keep the show on the road. It is clear from previous episodes of global imbalance that it is only the surplus countries that can safely make adjustments and reduce the imbalances, if the deficit countries do most of the adjusting the result is depression, disruption and slump as demand is sucked out of the global economy.

The UK is a very significant trade partner for the eurozone (see the table below) and, by running a large trade deficit, the UK is exporting a considerable amount of demand to the eurozone, and it is this injection of UK demand that is helping to keep the eurozone from falling into another recession and crisis. Note that it was the Italian banking system and not the British banks that needed emergency liquidity support over the weekend after the referendum. Economic conditions are poor in much of the eurozone, unemployment, even in core countries such as France is very high, and the eurozone banking system remains extremely fragile. The last thing the eurozone needs is to lose access to UK customers.

| The signficance of trade with UK for leading EU member states | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| The ranked importance of the UK as export partner | Percentage of exports sold to UK | Trade surplus with the UK in billions of dollars | |

| Germany | Third largest | 7% | 54 |

| France | Fifth largest | 7% | 14 |

| Netherlands | Third largest | 6% | 15 |

| Italy | Fifth largest | 5% | 14 |

| Spain | Fifth largest | 5% | 10 |

A political solution

Any long-term observer of the EU should be familiar with the shock referendum result. In 1992 the Danes voted to reject the Maastricht treaty. The Irish voted to reject both the Nice treaty in 2001 and the Lisbon treaty in 2008.

And what happened in each case? The EU rolled ever onwards. The Danes and the Irish were granted some concessions by their EU partners. They staged a second referendum. And the second time around they voted to accept the treaty. So why, knowing this history, should anyone believe that Britain’s referendum decision is definitive?

It is true that the British case has some novel elements. The UK has voted to leave the EU altogether. It is also a bigger economy than Ireland or Denmark, which changes the psychology of the relationship. But still – the EU has been built on deals and compromise, fudge and living to fight another day. Why should it change now.

Some time in September it looks like we will get a new Tory government and new prime minister. The new PM can meet his main EU counterparts with the Leave vote safely banked in his (or her) pocket. The referendum result should now act to focus the minds of the rest of the EU on solving Britain’s problems, the primary one being immigration. Although the Leave campaign has stirred up racism and xenophobia the problem with immigration is not primarily an issue of race (the incoming EU migrants are after all white) but it is to do with what happens if you create a free market in Labour, unrestricted travel and a Union which has a big permanently depressed economic zone with high unemployment, and another (the UK) with a growing demand for labour and very relaxed labour laws. The result has been a destabilising flow of migrant workers, and as the tensions over those massive migrant worker flows have built up the UK political system has been institutionally and structurally deaf to the voices of those who really don’t want mass migration on this scale. The communities that rebelled in the Leave vote are full of people and communities that the Tories don’t care about, and which most of the Labour Party membership is happy to right off as ill-educated, provincial bigots.

So a deal to significantly restrict the flow of migrant labour from the EU is key to winning back support from the Leave camp. Cameron couldn’t get a deal on the free flow issue because a commitment to the free movement of people has been totemic for the EU establishment and because they didn’t believe that there would be a Leave vote. The strains of prolonged economic stagnation and mass unemployment, combined with the mass refugee flows into the EU, have already eroded popular support for open borders, so there is a popular case for changing the blanket free flow position. The UK Leave vote, in the context of the surge of support for nationalist parties across the Union, should now make the EU leadership realise just how close to breaking the entire EU system has become. The terrible economic consequences of reducing UK demand for eurozone exports should full Brexit occur should focus their minds. A deal should be doable.

There are already signs that Britain might be heading towards a second referendum rather than the door marked exit. Boris Johnson, a leader of the Leave campaign and Britain’s probable next prime minister, hinted at his real thinking back in February, when he said: “There is only one way to get the change we need — and that is to vote to go; because all EU history shows that they only really listen to a population when it says No.”

Johnson’s main goal was almost certainly to become prime minister; campaigning to leave the EU was merely the means to that end. Once Mr Johnson has entered 10 Downing Street, he can reverse his position on the EU.

But would our European partners really be willing to play along? Quite possibly. You could see that in the talk by Wolfgang Schäuble’s finance ministry in Germany of negotiating an “associate” membership status for Britain. In reality, the UK already enjoys a form of associate membership since it is not a participant in the EU’s single currency or the Schengen passport-free zone. Negotiating some further ways in which the country could distance itself from the hard core of the bloc, while keeping its access to the single market, would merely elaborate on a model that already exists.

And what kind of new concession should be offered? That is easy. What Mr Johnson would need to win a second referendum is an emergency brake on free movement of people, allowing the UK to limit the number of EU nationals moving to Britain if it has surged beyond a certain level. Agreeing to an emergency brake on free movement of people might mean some modest limits to future migration. But that would surely be better than the much harsher restrictions that could follow a complete British withdrawal from the EU.

In retrospect, it was a big mistake on the part of the EU not to give Mr Cameron exactly this concession in his renegotiation of the UK’s terms of membership early this year. It was the prime minister’s inability to promise that Britain could set an upper limit on immigration that probably ultimately lost him the vote. Even so, with 48 per cent of voters opting to stay in the union, the result was extremely close. If the Remain campaign could fight a second referendum with a proper answer to the question of immigration it should be able to win fairly easily.

An alternative and attractive option for the Tories would be a snap election. It looks like the Labour party might be in a terrible condition so there is a chance for the Tories to boost their majority, perhaps by a lot. UKIP would be howling with pain at anything short of a clear Brexit, but this will be good for the Tories, it will allow them to unpick the uneasy Leave alliance with UKIP and at the same time a still strong UKIP will be sucking votes from a prostrate Labour Party.

The Tories need a two third majority in Parliament to bypass the fixed term act, that means they have to get the support of another 103 MPs on top of all the Tory votes. Assuming that the SNP, the Lib Dems, Plaid Cymru and Northern Irish parties would all vote to dissolves parliament if it meant avoiding a full Brexit, that would mean it would require the support of 27 Labour MPs for a dissolution. The question will be if in the conditions of chaos in the Labour Party is it possible to get 27 Labour MPs to support an election instead of a second referendum?

For this scenario of no Brexit or Brexit Lite to successful unfold just requires for our politicians, as well as the politicians in the EU, to behave, well, politically. There is still much to play for. The referendum wasn’t the end, its was the beginning.

It would be dangerous mistake if Remainers come to believe that the Leave vote was all about immigration, it was about a lot more than that, but that’s a topic for another post.