Something odd and a bit worrying is happening in local government in the UK, and I don’t mean the huge cuts in central government funding. All across the UK local authorities are moving into large scale property development as a way to generate income to compensate for lost government funding. This could be a deeply problematic development.

The squeeze on local government spending which started inn 2010 has been unprecedented in its scale and impact on local budgets. The “formula grant” which is the main grant paid to councils by the government: under it, for every £1 received by councils in 2010/11, they got just 73.6p in 2013/14. This is before the effects of inflation are taken into account. In total the government plans to slash grants to councils by £11.3 billion by 2015/16. More than 500,000 council workers have lost their jobs since 2010.

In this context many local authorities are desperate to fund alternative sources of revenue and income, and it is this desperation that has driven so many of them to embark on a program of property development for profit. All across the UK, local councils have been moving aggressively into the commercial property market or embarking on residential property development, either for sale or for the private rental market. The driving force behind this is the same one that pushed local governments in Japan to buy property in the 1980s bubble and that now prompts China to encourage manic property development from its municipalities: the need to plug gaps in their budgets after years of funding cuts from the central government.

The reason that local authorities can make quick money in the property market is because there is an irresistible combination of cheap finance (cheaper than the finance the private sector can access) and a buoyant property market. If local authorities can outbid almost all other participants in the commercial property market, it is because they have access to cheap and flexible funding from the Public Works Loan Board, an arm of the Treasury that has been helping finance capital spending by local government since 1793. Its interest rates are linked to those in the gilt-edged market which have been at exceptionally low levels since the financial crisis of 2007-08. At the end of 2016, according to estate agents Colliers International, local councils were able to access a 45-year loan from this ancient body at a fixed rate of just 2.45 per cent. Money borrowed at 2.5 per cent or so is typically going into property yielding 6-8 per cent or more.

The spending spree has been at its fiercest for shopping centres. Surrey county council last year spent £86m on The Mall, Camberley; Canterbury city council bought half of the £79m Whitefriars centre in the cathedral city, Stockport borough council bought the Merseyway centre in the town for £75m, while Mid Sussex district council spent £23m on another in Haywards Heath. They have also been busy buying offices, retail warehouses, industrial parks, solar farms, hotels, garages and country clubs. Increasingly this speculative investment activity is taking place beyond council boundaries.

These mainly English public sector investors are now a force in the market. According to Mat Oakley of estate agents Savills, they bought £1.2billion worth of property in 2016 and had spent at least £221 million by late March this year. Agents talk of a pipeline of current deals running into several hundred million pounds.

Everywhere the motive is the same: to generate additional revenue to maintain services — housing for the elderly, children’s centres, libraries and the rest — that might otherwise fall victim to the Treasury’s remorseless squeeze on local government finance. Another motivating factor is a change in local government funding rules. From 2020 local authorities will be allowed to keep 100 per cent of their tax revenues from businesses, rather than the 50 per cent they can at the moment. This is intended to compensate them for the shrinkage of grants from central government. It gives them a strong incentive to promote growth in their local economies to expand their business tax base.

For some, this has alarming echoes of earlier financial fiascos in the UK, especially the financial crisis. Lord Oakeshott, chairman of Olim Property, investment manager of £650m of commercial property for pension funds, charities and investment trusts, says: “English councils punting on property is an accident waiting to happen.” He adds: “There are real echoes here of Northern Rock, where many punters were lent all the purchase price of a property, and the Icelandic bank scandals, where councils played a market they didn’t understand for short-term income gain.”

How a borough council became a property company with a sideline in providing local government services

The starkest example of what is happening is the biggest local authority bet in commercial property to date which is the purchase last September by Spelthorne borough council of BP’s office park at Sunbury-on-Thames for a reported £360m. Finance for the Surrey site, which consists of 11 office blocks, was provided by the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB) in the form of 50 separate loans with maturities running from one to 50 years, amounting in total to £377.5m. This, the council told the Financial Times, covers transaction costs such as stamp duty as well as the purchase price.

The interest rates on this so-called blended annuity loan from the PWLB run from 0.83 per cent on the shortest-dated loans to a maximum of 2.26 per cent for longer loans. Under the sale-and-leaseback scheme, the oil company will be a tenant of the council for a minimum period of 20 years. Spelthorne declined to reveal the initial yield on the investment.

In a press release explaining its purchase of the largest privately owned office park in the UK, the council said funding from central government would be withdrawn completely in 2017-18, so it had been forced to find innovative ways to fund services and create new revenue. It has also been encouraging economic development within the borough to help stimulate growth in business rates. These are the same factors behind the wider local government spending spree in property.

For Spelthorne borough council the £377.5 million borrowings are huge in relation to its gross assets of just £87.7 million and net assets of only £39.7 million and gross income last year of £73.9 million. This is a very, very highly leveraged deal.

The BP office park purchase transforms the nature of the council. In balance sheet terms, Spelthorne borough council is now a property company with a sideline in providing local government services.

What could possibly go wrong?

The term used by local government officials for financing from the PWLB as “prudential borrowing” (or Pru-Bo), but given the dangers implicit in the big property bets being taken that may be an unfortunate label. The history of local governments dabbling in the markets is not reassuring. Most of the property investments made by Japanese cities in the 1980s generated huge losses in the 1990s, doing considerable damage to the public purse. In the US financial speculation has led to bankruptcy, most notably at Orange County in California, which was forced to declare itself bankrupt in 1994 after losing $1.6 billion on derivatives trading.

The difficulty for financially stretched councils in the UK, as Jennifer Wong, a vice-president at the Moody’s rating agency in London points out, is that this is “quite different territory for local government in terms of risk profile”. The revenues from the properties are inherently uncertain and the local authorities also face the same early-stage construction risks as private developers which is that on completion, the value of the properties are exposed to market fluctuations. The greatest risk arises in commercial property, relating to financial gearing, or leverage, whereby borrowing magnifies the potential profits or losses that result from changes in the market value of the asset. Many PWLB loans are for much longer periods than the leases the authorities have bought, so they could face an exit penalty on early repayment.

Local authorities are finding that borrowing on the full value of the property is especially tempting because borrowing at less than 100 per cent means the investment in property could squeeze spending on social priorities, as any initial downpayment would come out of the current budget. At the full 100 per cent a property can immediately make a positive contribution to the local authority budget as it pockets the margin between the borrowing cost and the higher initial yield on the property. The question then is whether it will stay positive. Tenants can, after all, go bust or the value of the property may turn out to have fallen when the lease expires.

In the worst-case scenario the local authority buys properties that are very large in relation to its revenue-raising potential and which turn out to be dud and illiquid investments. With the council’s finances dented by property losses, the rise in revenue or cuts in services required to meet its statutory commitment to balance the budget might be so extreme that a central government bailout would be unavoidable.

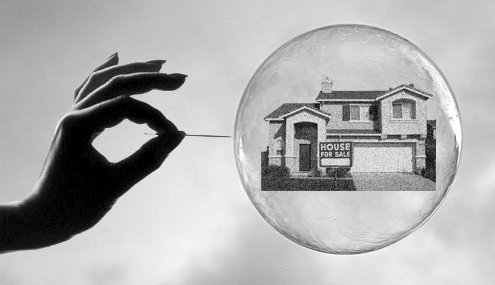

This incentive to borrow to excess indicates that the Treasury is helping to create an incipient public sector credit bubble while entrenching a culture of incautious risk-taking in local governments. As well as requiring much less due diligence than a commercial bank, the PWLB does not apply a loan-to-value discipline, whereby borrowings are capped at a given percentage of the purchase price. And it has plenty more funds to distribute because its outstanding loans, which stood at £65.3 billion in March 2016, are permitted under its current remit to rise to £95 billion which means the program of local authority property investments could continue to grow in scale for quite a while. The larger local authorities are also now turning to the capital markets where, as sovereign borrowers with low risk ratings, they can take on debt on terms even more favourable than those available from the PWLB.

There will in due course be a reckoning. Since the Brexit referendum a conspicuous casualty in property has been the shopping centre market, which has also been badly hit by the rise of online retail. Mike Prew, managing director and head of real estate at investment bank Jefferies International, calls it “a slow-motion train wreck”. Since local authorities revalue their properties annually and their auditors are required to report on whether their investments represent value for money, any damage will become public knowledge.

There is a larger irony in the role of the Treasury: under George Osborne and now Philip Hammond, it has caused local authorities to bear the brunt of its commitment to austerity. Yet via the PWLB it is simultaneously encouraging lowly paid local authority bureaucrats to behave like entrepreneurial risk takers on cheap public money.

The verdict of Olim’s Lord Oakeshott is telling: “As with Northern Rock and Icelandic banks, there’s a serious systemic risk to the property market and financial stability developing here, but the Treasury and Bank of England are fast asleep to it yet again.” The public accounts committee of the House of Commons produced a damning report in November that accused the Department for Communities and Local Government, which oversees local government finance, of complacency — especially in relation to the huge increase in property investment.

At a parliamentary hearing departmental officials argued that commercial investments were no more risky than managing social care demand pressures and appeared to have little grasp of the scale of local government activity in property or any understanding of the risk inherent in highly geared deals. Committee members worried that the commercial skills required in the property market “were not a good fit with local authority pay scales” and concluded that it “appears complacent about the risks to local authority finances, council tax payers and local service users arising from the increasing scale and changing character of commercial activities across the sector” (the summary of the report is here and the full report can be found here)

This concern was echoed in March in a speech by Baroness Wheatcroft, a member of the economic affairs committee of the House of Lords. Referring to Portsmouth city council’s purchase of shops in Redditch, a Mercedes showroom near Southampton and a warehouse near Gloucestershire as well as a deal on a local ferry terminal, she remarked: “I am prepared to believe that local authorities know a lot about social housing, but I am not convinced of their knowledge about Mercedes showrooms or ferry terminals.”