As the Labour Party conferences winds down and the left is confirmed securely in control of the party it is worth taking a moment to consider the task ahead. And it’s a very big task. A new Fabian report, ‘The Mountain to Climb‘, reveals that victory for the Labour party will be more than twice as difficult to achieve as in 2015.

The report looks at the likely effects of scheduled boundary changes and concludes that Labour will need to win 106 seats to secure a majority, reaching deep into middle England. It lists the ‘target’ seats Labour will need to win (prior to boundary changes) and suggests that the ‘victory line’ could be Harlow in England and Kirkcaldy and Cowdenbeath in Scotland.

Key points:

The decline of the UK Labour Party mirrors the general decline of support for social democratic parties across the western democracies but the impasse for the left has special characteristics in the UK. The UK’s electoral system means that in order to win power political parties have to be broad based internal coalitions because true external multi-party coalitions are very rare and usually fleeting. The big arc of UK politics, at least since the end of the 19th century and right through the 20th, has been the story of the Tory attempts, mostly successful, to build a centre right coalition bloc in order to secure power, and at the same time their attempts to prevent the formation of a centre left coalition bloc.

As suffrage was incrementally extended to working class men in the 19th century Labour emerged as a distinctive and separate political force, initially inside the Liberal Party. The crisis of WW1 and the massive (by historical standards) extension of state activity and state social programs, and the simultaneous emergence of a separate Labour Party terrified the Tories. Their fear was that a Labour-Liberal coalition would be unstoppable. In fact such a centre left party coalition never emerged and for most of its history the left of the Labour party has fought against and tried to undermine the creation of a centre left coalition electoral base for the party, thus offering the Tories an open goal.

Internal party coalitions are trying and difficult for party members. People want the political party they join to reflect their priorities and values, and resent the fact that in the UK system they have to share their party with peopler with very different priorities and values. In other political systems, ones that that regularly generate external multi-party coalitions, political parties can have a narrower idealogical and cultural focus, they can be ‘purer’, and as such can feel easier places to live for their members. In such systems the requirement of building a coalition in order to govern is conducted through difficult but mostly external negotiations where the trade offs and comprises are clear and explicit, and are an obvious cost of achieving participation in government. In the UK the system pushes all the messy business of coalition building inside the parties themselves. This means that in both parties, but especially in the Labour Party, members are always falling out of tune with their party leadership. The Tory members are always to right of the Tory leadership and the Labour members are always to the left of the Labour leadership.

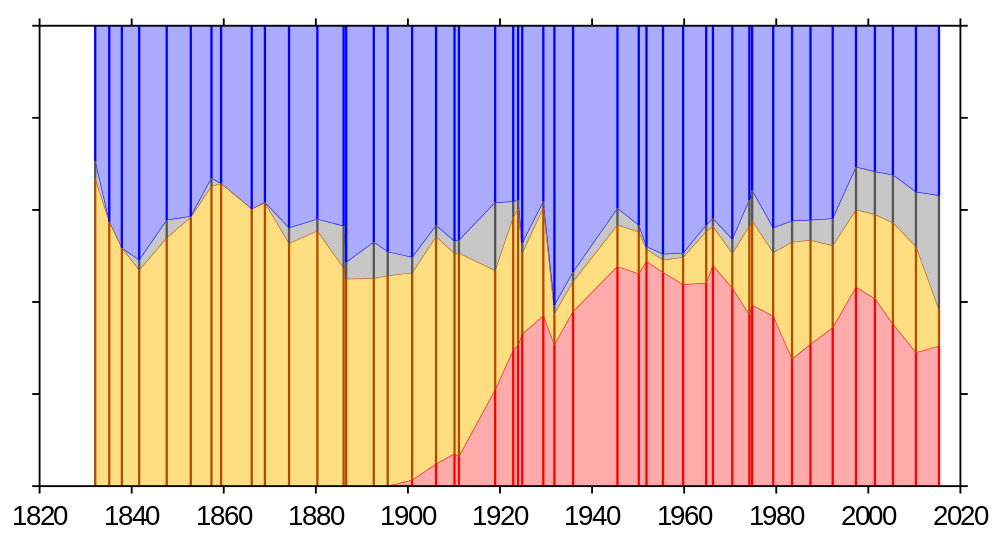

Historically in the UK the Right has always dealt with the tensions of a building a broad base party better than the Left. That is why the right has been in power for most of the last hundred years. Other than in 1945 (when the wholly unique social and political effects of five years of total national war mobilisation – partially administered by Labour politicians – had built up a massive base of support for Labour policies) the Labour Party has only ever managed to build a stable centre left bloc with a large majority in the house of commons twice: once in 1966-1970, and once from 1997 to 2010. Although it was in power between 1974 and 1979 Labour only ever had a precarious and paper thin majority in the Commons. The New Labour period was completely unique in that Labour managed to win large majorities for three consecutive elections. All the rest of the time it has been the right that has built, maintained and defended its centre right bloc and thus dominated the governance of the UK. And we all know what that feels like.

Yesterday I watched Tom Watson being heckled by Labour members at their conference as he tried to whip up pride in the achievements of the last Labour government. A significant proportion of the hall did not applaud his list of reforms delivered under New Labour. It didn’t look like a party that really wanted power.

My granddaughter will be born in the next month and given the scale of the mountain that Labour has to climb I expect that she wont see a Labour government until she is in secondary school, maybe even until she is ready for her gap year, maybe she will never see a Labour Government. Of course the Tories could melt down or be blamed for a Brexit fiasco, the global economy could tank in a second financial crisis causing a surge of support for the Left. But I am not holding my breath.

Good; thanks. Diagram vivid and instructive: where is it from?

Thanks for observations on internal coalitions and the specific UK experience. I wonder if there is also a relationship between what you write about the UK and Western European systems (countries) with or without a strong communist party? Where there was a strong CP, the so called “normal” configuration of parties might run (right-left) as Rightists/ fascists > centre rightists/ Christian Democrats> centrist Liberals > social democrats/ socialists > communists and/or other leftists. So with a minimum 5-element configuration, the external coalition combinations are numerous. What about countries with no strong CP? eg the old West Germany: where there is/was only a 3-element configuration (CD > Free Democrats >SPD). The internal coalition process within the SPD was painful and erratic, yet there was also the FD continually holding the balance of power, this being an external coalition partner, which itself changed the nature of the internal coalitions (within both CD and SPD presumably).

All this blurb applying to post WW2 and pre unification of course.

Not sure how all this is useful in the so called new configurations, for example the new right is not the same as the Old Right in all European countries, though Greece, Hungary and Poland all seem to be showing elements of interwar politics developing: I haven’t read much about the Baltics but I believe some of this has been observed there too.

Comments on this entry are closed.