The Italian banking crisis, and the emergency political manoeuvres to avoid a financial crisis, have escalated in the last few days. There is a lot at stake.

Two days ago Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Chairman of Societe Generale SA the French multinational banking and financial services company, said Italy’s banking crisis could spread to the rest of Europe, and that rules limiting state aid to lenders should be reconsidered to prevent greater upheaval. Germany has been leading a bloc in the EU that has been insisting that the Italian government cannot use public funds to recapitalise the insolvent Italian banks because such a move would break EU state aid rules.

“The whole banking market is under pressure,” the former European Central Bank executive board member said in an interview with Bloomberg Television on Wednesday. “We adopted rules on public money; these rules must be assessed in a market that has a potential crisis to decide whether some suspension needs to be applied.”

The statement from Smaghi was swiftly followed up by a statement from the Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi who said on Wednesday that the difficulties facing Italian banks over their bad loans are minuscule by comparison with the problems some European banks face over their derivative exposure.

Renzi’s comments appeared to be directed at Deutsche Bank, which has outstanding derivative positions running into trillions of euros, and marked an escalation in his war of words aimed at securing an EU deal over Italy’s troubled lenders. Speaking at a joint news conference with Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven, Renzi said other European banks had much bigger headaches than their Italian counterparts.

“If this non-performing loan problem is worth one, the question of derivatives at other banks, at big banks, is worth one hundred. This is the ratio: one to one hundred,” Renzi said. He did not directly name Deutsche Bank, but he has singled it out for criticism in the past, including last December, when he said he would not swap Italian banks for their German peers.

Rome is in talks with Brussels to devise a plan to recapitalise its lenders, including Italy’s third-largest lender, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (BMPS.MI), whose share price has dropped some 75 percent this year. Italian officials had argued that volatility caused by Britain’s vote to leave the European Union meant it should be given greater flexibility to prop up struggling banks.

However, German Chancellor Angela Merkel slapped down the suggestion, saying new rules for bank rescues, which reduce governments’ room for manoeuvre, had to be respected. Renzi told reporters that a solution was being found for Italy’s non-performing loan woes and said savers had nothing to worry about. But he said Europe had a wider credit problem that needed to be tackled.

“I am certain that the European authorities will think carefully about this in the coming days,” he said.

The Italian banking crisis and the eurozone

Italian banks have been in serious trouble for quite a while. Unlike the systemically important players in London, Paris, and Frankfurt, they weren’t exposed in a big way to the tightly coupled credit default swaps business, nor had they loaded up on US subprime exposures, both of which crashed in the 2008 crisis. As a result, the Italian crisis-related bailouts were modest: a mere €22.0 billion, versus €114.6 billion each for the UK and Germany, €174.3 billion for Spain, €39.8 billion for the Netherlands, and €23.3 billion for Belgium.

Italian banks got sick the old-fashioned way: on lending to businesses in their markets. As a direct result of the damage of the crisis to the Italian economy, many loans went bad; more got in trouble as austerity pushed more enterprises into distress. Italian lenders are regularly accused of cronyism and there no doubt were plenty of cases where sick borrowers were given more credit to make them look solvent. But that’s a common practice. Japan’s banks did that en masse in their post bubble years (a move the authorities later said was a big mistake) and in the US, home equity lines of credit were put into negative amortisation routinely (not only by not restricting access to the credit line when they were clearly having payment problems, but also encouraging borrowers to make token payments, like $5 a month, and declaring the account to be current).

The problem with the Italian banks therefore isn’t the complexity of the problem; it’s the scale, and the fact that Italy sits in the Eurozone, which has an absurd Heath Robinson bank resolution scheme that the authorities are unwilling to admit won’t work in practice (see my article ‘The EU’s banking union is a recipe for disaster’).

Italian banks have an estimated €360 billion of bad loans, which is roughly 20% of GDP. While the value of these loans is not zero, the losses that need to be taken to clean up the Italian banks are enough to threaten the stability and solvency of the several systematically important banks. The Italian banking system currently looks like a pack of cards wobbling in the wind and if one card falls it could bring down the lot.

The Italian banking system has been stumbling along for a while not dead but not actually alive, living from day to day (see my article ‘Italian zombie banks’). Having Italy’s banks remain in a zombified state means they aren’t giving much in the way of credit to businesses that need it. Italy has a high proportion of small to medium-sized businesses. That makes it particularly dependent on bank lending, so the dodgy banks are a drag on the economy.

Normally, the approach for this sort of mess is the one used in the US savings and loan crisis and in Sweden in its early 1990s bank meltdown: spin out the bad loans into a “bad bank,” where they are worked out to recover as much value as possible. The shareholders of the original bank, now a “good bank” are wiped out as it is recapitalised by the government, and top management and the board are replaced. The good bank is eventually sold.

The reason this route is blocked in Italy is the new EU banking regulation system that came into effect in January 2016 described in my article ‘The EU’s banking union is a recipe for disaster’ . The new rules mean that there is a very strict and inflexible burden-sharing hierarchy aimed at ensuring that:

(i) the use of public funds in bank resolution would be avoided under all but the most pressing circumstances, and even then kept to a minimum, through a strict bail-in approach; this means that whenever a bank gets in to trouble the EUs’ obligatory rules require that the capital of shareholders is immediately confiscated, followed by the confiscation of proportions of depositors money. A “bail-in” means that rather than using new money to restore bank equity, shareholders are wiped out then junior creditors if needed, and enough of the remaining creditor funds are forcibly turned into shareholders for the bank to have a decent level of equity so that it can become solvent again.

The danger is that this approach is guaranteed to cause bank runs at the first sign of trouble. The first time shareholder and depositor bail-ins were used in the eurozone was in Cyprus. Those banks had little in the way of borrowed money, so it was depositors who took haircuts. In the case of Spanish banks, many depositors had been persuaded to invest in equity-like instruments that they were falsely told were the same as deposits. That puts them near the head of the line for taking losses in the event of recapitalisation. In Italy, some banks have apparently resorted to similar chicanery, but not on the scale that took place in Spain. However, many consumers are investors in bank bonds, so they would be hit in the event of a bail-in. And given the Cyprus precedent, a bail-in of any size should scare depositors, and will lead them to move deposits from weak banks to stronger ones, creating liquidity stress and even bank runs. Already since the EU bank resolution came into affect in January 2016 there has been a massive (75% plus) decline in bank shares as investors flee the sector rather than face having their investments seized if a bank gets into trouble.

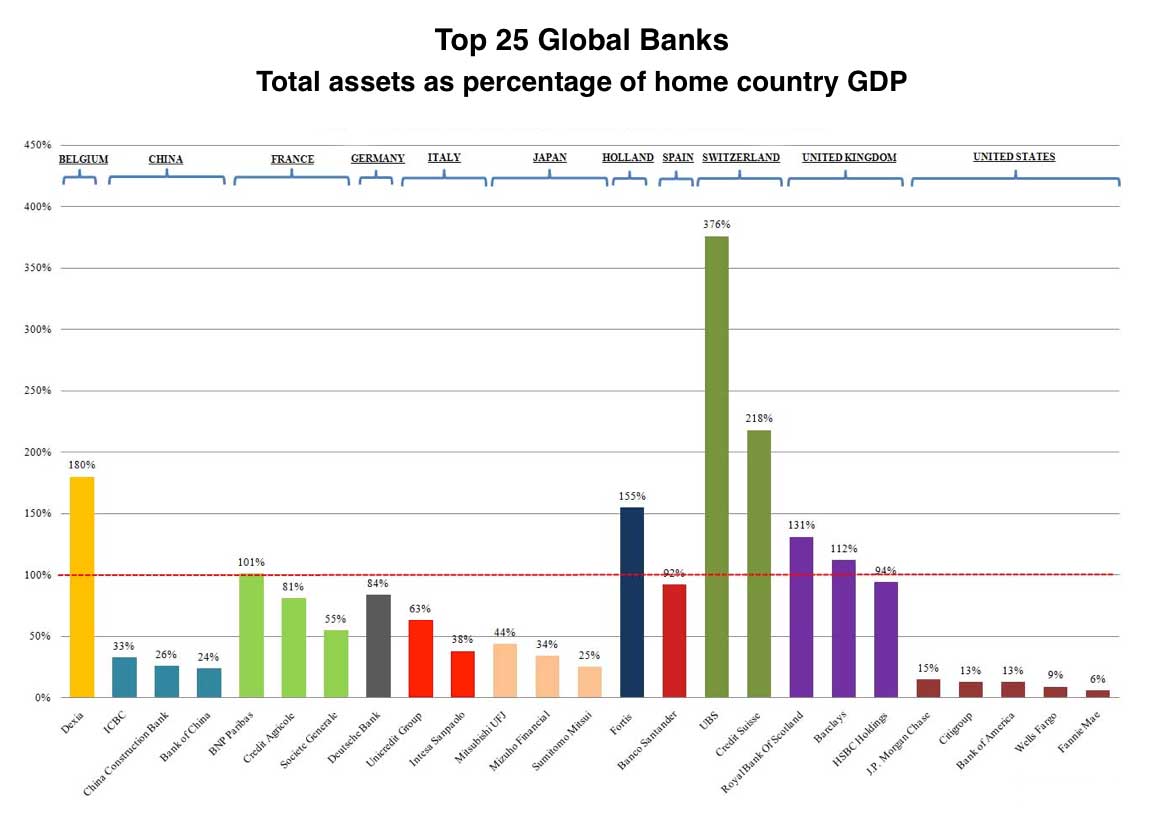

(ii) the primary fiscal responsibility for resolution would remain at the national level, with the mutualised fiscal backstop serving as an absolutely last resort. This means that if a very large systematically important bank gets into trouble the onus for bailing it out still falls on the host national government. As I explained in “Bank bailouts: Why the US made a profit and the UK won’t” many European banks are huge in relation to their host economies (see the chart below). Italy has individual banks that have assets that are 60% plus of Italian GDP. Bank failures and government rescues on that scale would completely wreck Italian government finances and send the Italian economy, already anaemic, into a deep recession. All of which would have severe knock on impacts across the eurozone.

It’s not as if Italian officials are ignoring this risk; they’ve proposed implementing a good bank/bad bank structure, and sought emergency relief so they can exceed Maastrict deficit limits to assist their banks. They were told in effect that their problem was not an emergency and they need to follow the unworkable bail-in regime. Renzi was rebuffed by Merkel when Italy tried again in the wake of the Brexit vote, arguing that the situation had become more dire. Merkel insisted that Italy needed to follow the new rules.

The Italian banking crisis has the potential to break up the Eurozone. It’s bizarre to see European officials taking a hard line with the UK, motivated by the perceived need to beat back threats like Marine Le Pen and Belgian and Spanish separatists, yet ignore the fact that Italy is as big a risk to the EU. That should imply they need to weigh political considerations along with the economic ones. But that doesn’t seem to be happening.

Italy’s deep economic malaise

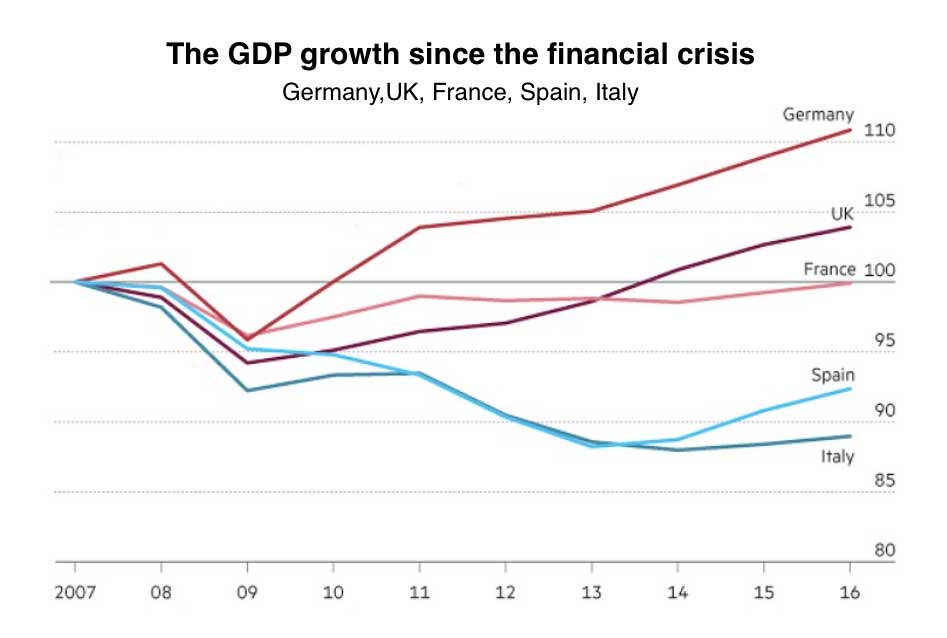

At the root of Italian banking crisis is the terrible performance of the Italian economy since the financial crisis of 2008. There essentially hasn’t been any recovery in the Italian economy since 2008. In fact, real GDP is today nearly 10% lower than it was at the start of 2008 and even worse – real GDP today is at the same level as 15 years ago! 15 years of no growth – that is the reality of the Italy economy.

In the decade prior to 2008 Italian NGDP grew more or less at a straight line. However, since 2008 actual nominal GDP level has fallen massively short of the pre-crisis trend.

There are numerous reasons for Italy’s lack of (both real and nominal) growth. One thing is the fact that Italy is in a currency union – the euro area – in which it should never had become a member. Italy’s deep crisis warrants massive monetary easing – in other words Italy needs a much weaker ‘lira’, but Italy no longer has the lira and as a consequence monetary conditions remains too tight for Italy. With no growth is it hard to see both private and public debt levels coming down in any substantial way and as a consequence we are very likely to see continuing stress in both the Italian banking sector and Italian public finances.

The political implications – Renzi rocked as Five Star surges in polls

The populist Five Star Movement has emerged as Italy’s leading political party, overtaking Matteo Renzi’s ruling Democratic party (PD) in four separate opinion polls that have exposed the growing vulnerability of the country’s centre-left prime minister.

According to polls released on Wednesday by Ipsos, the Five Star Movement is supported by 30.6 per cent of Italians, compared with 29.8 per cent for the PD. Similar polls in January had Mr Renzi’s party leading the Five Star Movement by nearly six percentage points. Three other surveys taken after the Brexit vote also showed the Five Star Movement ahead, with the next national elections due in early 2018. One by Demos released on July 1 showed the party ahead by a margin of 32.3 per cent to 30.2 per cent over Mr Renzi’s PD. Others by Euromedia and EMG showed the Five Star Movement with narrower leads of 0.5 and 0.4 percentage points. Another poll showed the Democratic party hanging on to a narrow lead.

In the 2014 European elections, shortly after Mr Renzi took office, the PD defeated the Five Star Movement by nearly 20 percentage points. The recent rise in the popularity of the Five Star Movement was shown when it won important mayoral elections across some of Italy’s largest cities last month, with the populist party’s candidates Virginia Raggi and Chiara Appendino respectively winning in Rome and Turin, Italy’s largest and fourth-largest city. Both positioned themselves as youthful voices promising to deliver practical change to disaffected citizens.

The Five Star Movement has called for a referendum on ditching the euro, and its growing popularity reflects a shift in public opinion against Mr Renzi and increases the chance that there will be a return to political instability. It will also raise alarm bells about the fate of an autumn referendum on constitutional reform on which Mr Renzi has staked his political career. He has threatened to resign should it be defeated.

The polls look even darker for Mr Renzi if the likelihood of a run-off between the two largest parties — which is called for under Italy’s new electoral law if no party exceeds 40 per cent — is taken into account. In those scenarios, the Five Star Movement would defeat the PD by as much as ten percentage points, as right-wing voters would coalesce around the protest party.

Prime Minister Renzi this week challenged PD members to stick with him, and called for aggressive campaigning in support of the October vote. “The referendum is not crucial for the destiny of an individual, but for the future credibility of the Italian political class,” he said on Monday.

Quite.