The current Greek debt repayment schedule is impossible to implement and it will never happen. That is basically the giant problem around which the entire dance of negotiations between the Greek government and the Troika has circled.

The Syriza government position is actually pretty simple:

Based on that strategic analysis the Greek government has now made public its own alternative restructuring plan that the government claims will cut its burgeoning debt load from the current 180 per cent of gross domestic product to just 93 per cent by 2020.

The plan is touched on in the 47-page counter-proposal Athens sent to its creditors Monday night (see page 44 in the document, posted by the German daily Tagesspiegel here). But it is given a full treatment in a new seven-page document authored by the government and entitled “Ending the Greek Crisis”. Brussels Blog got a copy and posted it here.

The restructuring plan is ambitious, offering ways to reduce the amount of debt held by all four of its public-sector creditors: the European Central Bank, which holds €27bn in Greek bonds purchased starting in 2010; the International Monetary Fund, which is owed about €20bn from bailout loans; individual eurozone member states, which banded together to make €53bn bilateral loans to Athens as part of its first bailout; and the eurozone’s bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, which funded the EU’s €144bn in the current programme.

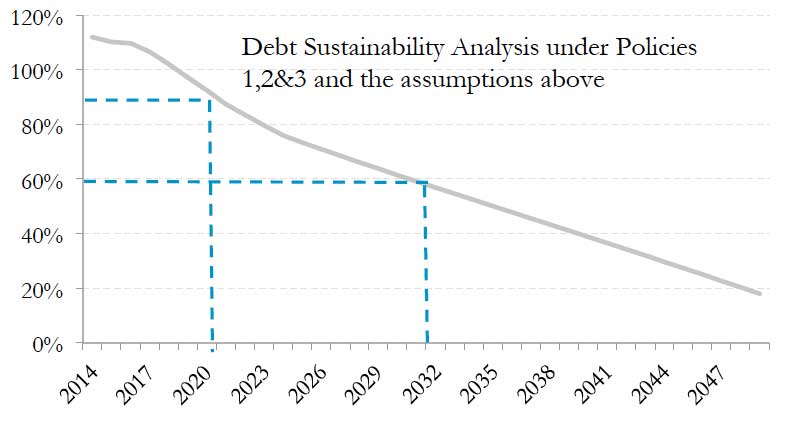

If all the elements of the new plan are adopted, the Greek government reckons its debt will be back under 60 per cent of GDP – the eurozone’s ceiling agreed under the 1992 Maastricht Treaty – by 2030, as this chart from the document shows:

Here is how the Syriza plan would restructure the Greek debt.

The European Central Bank

This part of the plan has already been publicly articulated by finance minister Yanis Varoufakis on several occasions, and is very straightforward: the eurozone’s €500bn rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) would loan Greece €27bn, which Athens would then use to pay off the European Central Bank (ECB) bonds.

The advantage to doing is is that the ESM’s loans are at longer maturities and lower interest rates than the Greek bonds held by the ECB, so it’s a debt restructuring without a real debt restructuring. Two of the ECB-held bonds come due in July and August, with payments totaling €6.7bn, so figuring out a way to deal with these is a matter of urgency.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF)

The proposal on dealing with the IMF involves the bonds held by the ECB covered in the previous section. These bonds should have been paying out interest – profits for the bondholders – just like all bonds, so the the €27bn owed to the ECB though its bond holdings includes €9bn in profits. If these bonds were to be purchased by the ESM as proposed the Greek government is asking that the ESM forgoes the payment of this owed profit. It would a bit bonkers for EU institutions to make a profit out of the Greeks under current circumstances so forgoing the profit seems a reasonable request should the ESM agree to buy the bonds.

The Greek plan would use this €9bn to pay off nearly half of what it owes the IMF early. The rest of the IMF debt would paid the old-fashioned way, by either raising funds on the market (which Greece currently can’t do but might be able to do if there is a comprehensive debt deal) or using new bailout loans.

The early payment of IMF loans would help lower Greece’s overall debt levels but is contingent on eurozone creditors agreeing to the ECB restructuring proposal outlined in the ECB section.

Paying back the first bailout

When Greece was first bailed out in May 2010 (a €110bn programme, of which only €73bn was actually disbursed), there were no eurozone-wide institutions to dole out rescue funds. So all eurozone governments agreed to together make bilateral loans to Athens, with the exception of Slovakia, which ultimately rejected the plan.

These loans, formally called the Greek Loan Facility, have been repeatedly restructured, with their interest rates lowered and their payment schedules extended for years. The new Greek plan would extend those payment schedules even further.

The first idea is a so-called “perpetual bond”, which is exactly what it sounds like: a loan to Athens that is never paid back in full, but has interest payments that go on forever. As odd as that sounds, these perpetual bonds are not new in the realm of government financing, and the Greek government proposes annual interest payments of 2-2.5 per cent of the value of the bond.

The problem with a perpetual bond is that it is essentially an admission that Greece will never pay back what it owes to eurozone governments, which would be hard to sell politically in capitals like Berlin. The Greek plan foresees that difficulty and offers as an alternative lengthening the payment period for the GLF bailout loans to 100 years. Again such long repayment periods are not unknown in the realms of government borrowing, last year the UK government paid of the last of the bonds it sold to finance the First World War.

Another possibility offered up by Athens are “GDP indexed bonds”. Again, they are what they sound like: Greece would only have to make payments to creditors if its economy starts growing again, and in amounts tied to the rate of growth. These sort of GDP growth linked bonds were used to restructure the German debts after the Second World War.

Eurozone governments have expressed a willingness to extend maturities of the Greek Loan Facility loans, so the most likely option to get any traction here is the 100-year maturities. But the general muddle amongst the overcrowded creditors side of the table means that actually getting such an agreement signed in time will be difficult.

Paying back the second bailout

Once the current bailout agreement is completed, the eurozone’s old bailout fund, the The European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), will be owed €144bn by Greece. Those loans are at already very low rates, with very favourable repayment schemes. But the new Greek plan offers something far more radical. It would break the EFSF loans in half, with one half of the outstanding debt being restructured into a loan paying 5 per cent interest (double the 2.5 per cent currently paid) and the rest essentially being written off. The write-off would occur in phases under the Greek plan. At first it would become a zero-coupon bond (jargon for an interest-free loan), which would gradually be cancelled.

The argument for this plan is that the annual interest payments made by Greece would remain the same (5 per cent of half the loans is the same as 2.5 per cent of all the loans). But by writing off half of the original loan total, Greece’s overall debt load is cut substantially. This makes reaching the target debt figure of 60% of GDP much easier and would help to rebuilt confidence in the Greek economy and thus create a more favourable investment environment which in turn will help restart growth in the Greek economy. And without growth no debts will be repaid

The Greek plan looks technically practical but politically very difficult. It should obvious to everyone, including the Greek creditors, that trying to squeeze a decade long surplus out of the Greek economy in order to repay unrestructured current debts is just simply never going to happen.

So there really are only two alternatives, restructure the debts or allow a disorderly default to occur with unknown (but probably bad) consequences for both the Greek people and the rest of the eurozone.

One attractions of the Greek plan is that it would mean that the profile of the creditors is simplified, the IMF and the ECB can fade into the background and whole thing can be managed via the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

If a successful deal was agreed the danger of Grexit would fade and this should put a stop to the current capital flight which has all but destroyed liquidity in the Greek banking system, capital would flow back into the country and the Greek banks could stabilise.

The problem for the EU side is that they have not prepared their respective electorates for such a deal and by constantly talking up the need for the Greeks to pay their debts in full the EU governments have boxed themselves in politically.