On 1 January 2016 the EU’s banking union, which was planned to be an EU-level banking supervision and resolution system, officially came into force. The move to the banking union is the most significant regulatory outcome of the financial crisis of 2008, and the resulting Eurozone crisis of 2010, and it is claimed that even in its current incomplete form the banking union is the single biggest structural policy success of the EU since the start of the financial crisis. However a closer look reveals that, like so many other parts of the currency union architecture, it is deeply flawed, and that the banking union is the latest step in the EU’s post-crisis creditor-led path of austerity and asymmetric adjustment.

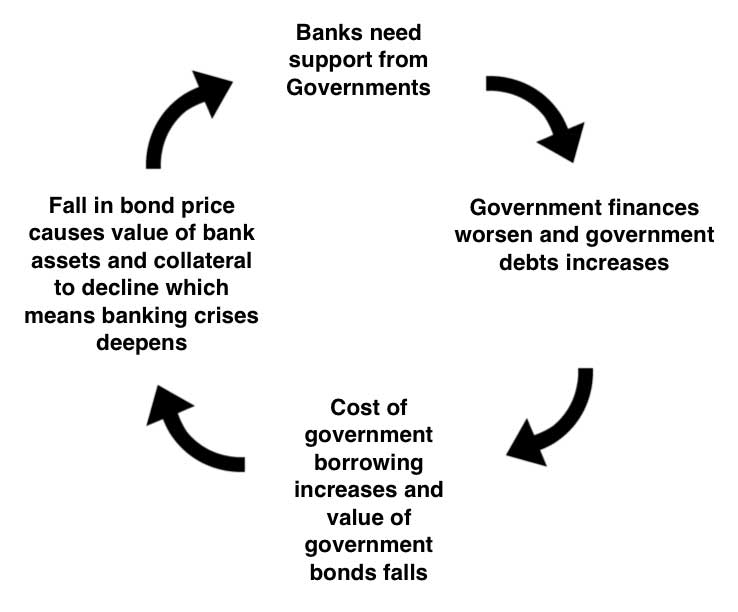

In its original intention, the banking union was supposed to break the vicious circle between banks and sovereign debt by mutualising the fiscal costs of bank bail outs. As explained in “Too big to bail – how the banks crashed the eurozone” the banking system had adapted to the strange new world of the single currency by building a huge speculative and dangerous credit bubble using eurozone government bonds as raw material for a credit based money machine. In the years between the creation of the euro in 2000 and the crises of 2010 the banks suffered from the delusion that all government debt in the eurozone was equally safe and therefore interest rates on these eurozone bonds had almost harmonised. The banks also believed that eurozone bonds were an ultra safe financial asset, and therefore the bonds of any country inside the eurozone could be accepted as equally rock solid collateral when making financial and credit deals. When the Greek debt crisis erupted in 2010 the banks suddenly realised that these eurozone bonds were not mutually guaranteed and the cost of borrowing for the riskier weaker economies of the eurozone suddenly started to shoot up threatening to drive a number of government into severe fiscal crisis. What made this crisis so deadly was that there was a powerful feedback loop in operation. Eurozone bonds had become the raw material for maintaining the risky but very popular European banking game of borrowing short to lend long. As the value of eurozone bonds from the periphery states fell and yields rose the banks began to run out of the essential raw material that kept their money machine running. And this came just as banks across the EU began to suffer big losses related to the sub-prime collapse in the US and the collapse of the property bubbles in Ireland and Spain. There was a real danger that a cascade of bank failures could bring down the European banking system and a number of governments had to bail out their national banking systems at great costs. This caused the fiscal condition of a number of eurozone governments to sharply deteriorate, this led a further devaluation in eurozone bonds and this in turn further weakened banks which meant they needed even more government support. It was a deadly loop.

Initially the European decision-makers viewed the eurozone crisis as being one primarily related to fiscal issues, and so the emphasis was all on reducing spending, reducing deficits and achieving ’sound’ public finances. Eventually there was a belated acknowledgement by eurozone leaders, years into the crisis, of the non-fiscal, namely banking and monetary, nature of the eurozone crisis. As the sovereign debt crisis, in 2012 engulfed Spain and Ireland, two countries that in the pre-crisis years had registered among the lowest deficit/debt ratios in the eurozone, European policy makers were forced to recognise that leaving the responsibility to deal with the post-crash banking crises in the hands of individual member states – essentially leaving national policy makers with no choice but to finance their bank-rescue operations (or bailouts) with national fiscal resources – had ended up saddling certain countries (especially those of the eurozone’s periphery, which had experienced massive speculative capital inflows from German and French banks and a huge build-up of private debt in the years leading up to the crisis) with unsustainable levels of public debt, leading to dangerous imbalances that now threatened the financial stability of the euro area as a whole.

As the governor of the Bank of England Mervyn King had argued early in the crisis, ‘global banks are global in life but national in death’.

The focus on austerity as the main policy response remained unchanged for political rather than economic reasons but there was a recognition of the need for substantial changes in the European policy stance on bank resolution, aimed at relieving individual countries of the fiscal responsibility for bank-rescue operations and putting an end to the fragmentation along national lines of banking and monetary conditions. The establishment of a joint public funding mechanism, a so-called common ‘fiscal backstop’, for the whole euro area was considered essential for this purpose. The prerequisite for a mutualisation of bailout costs, however, was the centralisation of the responsibility for banking supervision and resolution in the euro area, so as to preclude the externalisation of the fiscal costs of regulatory failure by countries with lax regulatory regimes. Such were the considerations that drove European leaders on 29 June 2012 to explicitly affirm the need to break the ‘vicious circle between banks and sovereigns’, adding that ‘when an effective single supervisory mechanism is established, involving the European Central Bank (ECB), for banks in the euro area the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) could be used to recapitalise banks directly’.

In the course of constructing the banking union, however, something bad (but in the context of the real dynamics of the eurozone very predictable) happened, the centralisation of supervision was carried out decisively but in the meantime its core and essential component (that is, the centralisation of the fiscal backstop for bank resolution) was all but abandoned. The main driver for the watering down of fiscal mutualisation was Germany along with its allies in the eurozone. The aim of the German driven changes in the Banking Union system was, as always with German economic and eurozone policy, to enhance the power of centralised pan-zone regulation whilst reducing any financial exposure for German tax payers.

The key amendments forced through by the German led bloc were:

a) the exclusion from the banking union of any common deposit insurance scheme;

b) the retention of an effective national veto over the use of common financial resources;

c) the likely exclusion of so-called ‘legacy assets’ – that is, debts incurred prior to the effective establishment of the banking union – from any recapitalisation scheme, on the basis that this would amount to an ex post facto mutualisation of the costs from past national supervisory failures (though the issue remains open)

d) most importantly, a very strict and inflexible burden-sharing hierarchy aimed at ensuring that (a) the use of public funds in bank resolution would be avoided under all but the most pressing circumstances, and even then kept to a minimum, through an application of a strict bail-in approach; and that (b) the primary fiscal responsibility for resolution would remain at the national level, with the mutualised fiscal backstop serving as an absolutely last resort.

Only once the national sources of bail out funding has been exhausted, and even then under very strict conditions, can the banking union’s Single Resolution Mechanism’s (SRM) and the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) be called into action. In short, when a bank runs into trouble, existing stakeholders – namely, shareholders, junior creditors and, depending on the circumstances, even senior creditors and depositors with deposits in excess of the guaranteed amount of €100,000 – are required to contribute to the absorption of losses and recapitalisation of the bank through a write-down of their equity and debt claims and/or the conversion of debt claims into equity. This passes almost all the risk back to the national banking systems and to the national level, it means that the key pillar of banking union, that the entire eurozone stands collectively as guarantors behind the entire eurozone banking system has been weakened to such a degree as to make it meaningless.

Notwithstanding the banking union’s problematic burden-sharing cascade the Single Resolution Fund (SRF) presents numerous problems in itself. The fund is based on, or augmented by, contributions from the financial sector itself, to be built up gradually over a period of eight years, starting from 1 January 2016. The target level for the SRF’s pre-funded financial resource has been set at no less than 1 per cent of the deposit-guarantee-covered deposits of all banks authorised in the banking union, amounting to around €55 billion. If a bank gets into trouble and seeks support from the SRF all its unsecured, non-preferred liabilities must have been written down in full first (meaning the bank must first renege on its unsecured debts) and the SRF’s intervention will be capped at 5 per cent of total liabilities. Forcing a bank to renege of its own debts before it can seek external support from the RSF is an extreme measure that would in itself have serious spillover effects because it would spread bad debt and asset write downs throughout the banking system. This means that, in the event of a serious banking crisis, the SRF’s resources are unlikely to be sufficient (especially during the fund’s transitional period) and are designed to be deployed in such a way as to allow significant contagion and therefore of allowing the failure of a systemically important big bank to damage the entire the financial system.

If a bank remains undercapitalised even after all the aforementioned sources of resolution financing have been exhausted – and even then, under very strict conditions – countries may request the intervention of the existing European general and permanent bailout fund, the ESM, through its new direct recapitalisation instrument (DRI). The way in which the instrument has been implemented, however, raises doubts as to its practical significance. The DRI’s rules raise significant barriers to the activation of the DRI even in situations where recapitalisation with public funds appears justified. Most importantly the eligibility criterion for assesing whether DRI can be offered directly to the banks explicitly takes into account the alternative of indirect bank recapitalisation by the ESM, by way of a loan to the relevant national government. The new rules say that unless this form of assistance is bound to trigger by itself a drastic deterioration of the recipient country’s fiscal prospects, it should be preferred over the DRI. In other words, the DRI is only available in situations where a country is unable to finance the bailout from its own national budget without thereby undermining its fiscal prospects in a drastic fashion. This means if a national government were forced to bail out a large bank and in the process incure very high levels of new public debt the new direct recapitalisation instrument would not be deployed. Given that the whole thing is being managed by the very same people who thought, and continue to insist, that the Greek loans are sustainable, it is reasonable to assume that under the DRI system national government could still find themselves saddled with huge amounts of debt because of the need to finance a bank bailout. The new arrangements of the banking union does everything possible to prevent and preclude any direct bailout of banks by European entities and does everything it can to load the burden of the bailout back onto national governments. This paves the way once again for private banking debt being transformed in national public debt.

If a government cannot meet the costs of a bank bailout without getting into fiscal distress it can go to the ESM for a loan. This is reliant upon the approval of the Commission, in liaison with the ESM’s managing director, the ECB and, wherever appropriate, the IMF, in other words the Troika. If a country is forced to seek support from the ESM (and given the weakness of the DRI system that is quite likely to happen) member states requesting financial support to deal with a bank failure will be on the receiving end of the Troika’s dreaded conditionalities, including where appropriate those related to the general economic policies of the ESM member concerned. In other words, those states whose banks (not governments) run into trouble and thus require financial assistance by the ESM will likely be forced to implement the same kinds of austerity and structural adjustment programme – public-sector cuts, wage reductions and so on – as the other recipients of sovereign loans have been forced to implement in recent years.

These people still think the Greek program is going well and if there is another crisis somewhere else the same sort of toxic super deflationary policy can be rolled out once again.

Even in the unlikely event that a bank is granted access to the DRI before it can receive direct injections from the shared fund the requesting government must either provide the capital needed to raise the bank’s minimum capital ratio to 4.5 per cent of its assets, or if the institution already meets the capital ratio, make a contribution ranging between 10 and 20 per cent of the ESM contribution. What this means is that under the banking union arrangements, national governments will be saddled with the primary financial responsibility in relation to publicly assisted bank bailouts. Even where a eurozone government finds itself in the unenviable position of needing to finance the recapitalisation of systemically important banks, while being fiscally too weak to do so without external support, the recapitalisation will take place, as a rule, via the national government’s own budget and finances, with the ESM providing only indirect assistance, in the form of a loan to the national government. The new direct recapitalisation instrument (DRI) is unlikely to be used in other than wholly exceptional circumstances (not least, because of the need for unanimity in the ESM’s Board of Governors for its activation) and even then, the country hosting the failed bank will need to share a considerable portion of the financial burden even though the the troubled bank’s supervision will be taken out of its hands and run by the new centralised authorities of the banking union system.

“…the known features of the [banking union] instrument are such that it is hard to see how it could possibly sever the sovereign-banking link. While it requires important private sector participation as a precondition, the ESM direct recap instrument still puts considerable burden on the State.”

Silvia Merler: Comfortably numb: ESM direct recapitalisation

The cumbersome nature of the banking union arrangements, the need for unanimity in the ESM’s Board of Governors for its activation of emergency support, the numerous caveats aimed at avoiding any possible pooling of the fiscal costs of a bank bailout, should be viewed in the context of what actually happens when a big bank goes bust. When big banks go bust it happens very quickly, often in a matter of days. Although the result of a long preceding period of poor management, excessive risk taking and bad lending, an actual bank failure usually occurs very fast because banks try until the last minute to wriggle out of insolvency. Given the sudden nature and the large scale of a big bank failure, fast decision taking is essential to prevent dangerous contagion in the financial system. During the 2008 financial crisis events moved very fast and some decisions were made in a matter of hours or during overnight emergency planning sessions. Does anybody think that the new banking union system, with all its layers of complex bureaucratic decision making, is designed to be able to very quickly deploy large amounts of funding to a bank in an emergency? In reality the only agency capable of doing that will continue to be national governments which means the cost of preventing a systemically important bank from going bust will once again be funded via national governments. Once again the cost of bailing out banks could wreck the finances of a national government. Once again national governments will be bailed out by the Troika. Once again this will involve an imposed restructuring program founded upon austerity.

Even the IMF has openly expressed doubts about the planned backstop, noting that ‘centralised resolution resources may not be sufficient to handle stress in large banks’. The overall amount that the ESM will be allowed to disburse for all bank recapitalisation has been capped at a relatively puny €60 billion (though the limit is allegedly flexible), more or less the same amount expected to be raised through the privately funded SRM. Though a large sum, it is a drop in the ocean compared with the balance sheets of Europe’s massive banks. The euro area is home to a very large banking sector, with total assets amounting to more than three times the region’s GDP, concentrated for the most part in the hands of large systemic banks, including a number of global systemically important banks, whose recapitalisation could conceivably require huge resources. To get an idea, the average balance sheets of the European Union’s 30 and 15 largest banks (€800 billion and €1.3 trillion respectively) are 13 and 21 times larger than the proposed recapitalisation limit. Not only are these banks too big to fail – they are too big to bail. The failure of any of them – even assuming that it would take place in isolation, rather than as part of a wider systemic crisis – would require the mobilisation of huge financial resources. This is also proven by the recent crisis, with certain large banks each individually receiving public assistance in excess of €100 billion.

One could still argue that the bail-in mechanism represents a step forwards vis-à-vis the bailouts of recent years, by limiting to some extent the burden placed on national governments and thus it can be claimed that the banking union does indeed address the need for ‘socialisation’ of the costs of banking crises. The crucial point to understand here is that the bail-in of creditors is indeed a great tool to have at one’s disposal, as there are undoubtedly numerous cases where saving a bank by making the private sector creditors carry the costs through a bail-in might be preferable to a publicly funded bailout. But this has to be decided on a case-by-case basis. The problems arise when member states are forced by the new regulatory and mandatory structures and rules of the banking union to automatically resort to the bail-in as the primary method of saving a bank, regardless of the potential consequences of such a move, of the nature of the bank’s problems, or of the wider macroeconomic context. This is especially true in light of the extreme disequilibrium between banking systems in the EU, itself a reflections of the wider social and macroeconomic imbalances between core and periphery countries. As the ECB’s recent stress tests have revealed, the banks with the largest capital shortfalls are all located in the countries of the periphery, which have been hit the hardest by the crisis: Italy, Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus. This is not surprising: various studies have shown that there is a clear link between a country’s negative macroeconomic performance and the capital adequacy of its banks. This is evident from the dizzying and rapidly-growing volume of non-performing loans (NPLs) in these countries which are a direct result of the austerity policies pursued in recent years and, of course, the main reason why periphery banks failed the ECB’s stress tests.

All these concerns about the weaknesses of the new banking union arrangements would be relatively academic if the European banking system was in robust good health. Unfortunately it is not, European banking is actually very sick and the condition of the banking system, after years of austerity induced stagnation, is getting worse.

The deep malaise of the Eurozone banks

Eurozone banks have seen their shares plummet by nearly 30 percent and yields on their bonds surge since the start of the year, as investors already worried about thinning profits and uncomfortably high levels of bad loans in some countries, were spooked by the mandatory bail-in of private investors included in the banking union. The selloff makes it more expensive for banks to raise capital on the market by selling shares or bonds. If this situation were to last, it would dent banks’ capacity to grow their balance sheets by extending new loans to companies and households. This would jeopardise a tentative rebound in lending driven by the ECB’s ultra-easy monetary policy. Bank lending in the euro zone started growing again in 2015 after shrinking for three years, but data for December data pointed to a loss of momentum. Adjusted loans to euro area residents excluding governments rose a meagre 0.4 percent in the last month of 2015, the slowest pace in three months.

A key transmission channel is the market for Additional Tier 1 (AT1) notes – bonds that can be converted into equity under certain conditions and on which the issuer can decide whether or not to make coupon payments. Banks have relied on issuing these notes over the past few years to shore up their balance sheets and build buffers to absorb future losses. European banks have been issuing around €30-40 billion worth of AT1 bonds in each of the past two years. But after a sharp selloff since the beginning of the year, the supply of new issues has dried up, with Italy’s Intesa Sanpaolo and France’s Credit Agricole the only two European banks to have sold new bonds this year. If this key market were to remain shut for a long time, banks would be faced with an uncomfortable choice between issuing AT1 bonds at prohibitive yields, selling equity at deep discounts, or shrinking their balance sheet by lending less. Deutsche Bank, which posted its largest ever annual loss last month, saw yields on its AT1 notes go up by a quarter or more since the start of the year. They now yield between 12.6 percent and 15.7 percent. The bank sought to calm investors this week by saying it had “sufficient” reserves to make due AT1 payments. Similar or higher yields are bid on AT1 bonds issued by Italy’s biggest bank, UniCredit and Spain’s No.3 lender Banco Popular after a sharp rise since the start of the year.This means that, if these banks were to issue AT1 bonds now, they would need to pay a yield higher than current market prices in order to attract buyers.

The eurozone banking system is in a very weak and fragile state, reflecting the financial costs of the long years of stagnation and austerity. Italy is an example of the the problems of eurozone banks. Italian banks own €400bn of Italian government debt and have effectively used cheap funds from the European Central Bank to prop up the Italian treasury.

The Italian banks fared relatively well during the financial crisis and therefore didn’t require almost any government aid at the time; since then, as a result of the country’s prolonged economic stagnation, itself the result of EU-sanctioned austerity, the balance sheets of Italian banks have severely deteriorated, and today, after a seven year long build-up of non-performing loans, are facing a system-wide crisis. A number of small and medium-size Italian banks are technically insolvent due to desperately high levels of non-performing loans. Now that depositor bail-in is on the horizon, the Bank of Italy has woken up. It has broken up four distressed Italian banks, creating four “bridge banks” and four “bad banks”, and bailed in subordinated debt holders. The Italian government has been in talks with the Commission for months over its plan to create a ‘bad bank’ to help offload some of the banks’ bad debt; at the time of writing, though, the Commission (the same Commission that by mid-2009 had approved €3 trillion in guarantee umbrellas, risk shields and recapitalisation measures to bail out Europe’s banks) continues to block the government’s plan, on grounds that it would amount to a violation of state aid and banking union rules. Even if the Italian government finally has its way, it would still amount to little more than a Band-Aid, and one that the Commission is unlikely to grant to other countries.

The banking union bail in of creditors regulations also threatnes to capsize the very fragile Greek banking system. The Greek economy is deeply depressed, and large amounts of money have left the country. There isn’t much in the way of senior unsecured debt and uninsured deposits to bail in, and just about all of it is the working capital of Greek businesses. The consequences for the Greek economy of wiping out the working capital of Greek businesses overnight don’t bear thinking about. Understandably, the ECB ruled out depositor bail-in for Greece.

This caused a huge problem. To avoid depositor bail-in, the four large Greek banks had to build up their capital buffers – fast. So they did some of the silliest rights issues ever seen, issuing large amounts of shares at deep discounts and causing their stock prices to collapse. The share price of the National Bank of Greece fell so low the NASDAQ suspended trading in its shares. However, all four banks did manage to raise a reasonable amount of capital, though they also needed to tap the €10 billion set aside for bank recapitalisation in the first phase of the current Greek bailout deal. But they desperately need the asset side of their balance sheets to improve if they are to avoid future bail-ins and that will only happen if the Greek economy begins to recover and grow quickly.

As a result of the new banking union system, Italy, Greece, and any other country that faces a similar situation, will have little choice in dealing with its ailing banks than to (a) force losses on the banks’ bondholders (often including large numbers of small savers/taxpayers, pensions funds, etc) or (b) accept a take-over oftheir national banks by foreign capital (given the limited availability of national capital). This will almost certainly lead to an increased ‘centralisation’ of capital, characterised by a gradual concentration of capital in Germany and the other core countries of the monetary union, through mergers, acquisitions and liquidations, and to the relative ‘mezzogiornification’ of the weaker countries of the union. In this sense, the banking union is likely to exacerbate, rather than reduce, the core-periphery imbalances.

The new bail-in rules also make countries susceptible to bank-run-style self-fulfilling panics. There is reason to believe that this process is already underway: by looking at the ECB’s TARGET balances, an excellent measure of intra-EMU capital flows, it would appear that periphery countries are experiencing massive capital flight towards core countries, almost on par with 2012 levels. It wouldn’t be far-fetched to imagine that this is due to depositors in periphery countries fleeing their banks for fear of looming bail-ins, confiscations, capital controls and bank failures of the kind that we have seen in Greece and Cyprus.

Germany escalates

Not satisfied with successfully building a banking union that creates a rigid and austere system regulating the way banks are rescued whilst preventing any meaningful mutualisation of risk or costs, the German Council of Economic Experts has proposed a new plan to impose “haircuts” on holders of eurozone sovereign debt. The plan has the backing of the Bundesbank and most recently the German finance minister, Wolfgang Schauble, who usually succeeds in imposing his will in the eurozone. This is a very dangerous move because the last crisis of the eurozone in 2010, which was an existential threat to the entire eurozone system, was only resolved when the ECB stepped in with the famous ‘Draghi put’ when it promised to do whatever it took to save the euro. This was interpreted by the markets as the ECB effectively guaranteeing eurozone sovereign debt and this in turn meant the yields on the bonds of the weaker heavily indebted countries could fall which made their debts manageable.

Under the scheme, proposed by the German Council, holders of eurozone government bonds would suffer losses in any future sovereign debt crisis before there can be any rescue by the eurozone bail-out fund (ESM). This sovereign “bail-in” matches the contentious “bail-in” rule for bank bondholders, which came into force in January as part of the new banking union. The banking union bail-in clause led to a drastic sell-off in eurozone bank assets this year, and the new German plan could become self-fulfilling all too quickly, setting off a “bond run” as investors dump their holdings of eurozone government bonds to avoid a haircut.

Countries such as Italy, Portugal and Spain would be powerless to defend themselves since they no longer have their own monetary instruments. The German Council says the first step would be a higher “risk-weighting” for sovereign debt held by banks, and a limit on how much they can buy, with the explicit aim of forcing banks to divest €604bn of eurozone bonds. They would have to raise €35bn in fresh capital, deemed “manageable”. The German Council says the “regulatory privileges” of sovereign debt held on bank books should be phased out. It should no longer be treated as “entirely safe and liquid” under the banks’ liquidity coverage ratios, or be exempt from capital requirements. “The greatest risks are for banks in Greece, Portugal, Spain, Ireland and Italy,” it said.

The announcement of the German plan is courting fate at a time when there are signs that the yields on eurozone bonds are once again beginning to diverge just as they did in the 2010 crisis. Portugal is already in the eye of the storm, facing a slowing economy and a clash with Brussels over austerity. The risk spread on Portugal’s 10-year debt surged to 410 basis points over German Bunds last week, pushing borrowing costs back to unsustainable levels in real terms. Portugal’s public debt is 132% of GDP. Total debt is 341%, the highest in Europe. The country is in a debt-deflation trap and requires years of high growth to escape. If the crisis endures, worries about a fresh Troika rescue for Portugal – and what the terms for debt-holders might be – could take hold quickly. There was no haircut on sovereign bonds when Portugal was bailed out in 2010, threatening one now could spook a stampede out of eurozone bonds and very quickly precipitate a repeat of the 2010 crisis. The only thing currently buoying up price of peripheral eurozone bonds is the extensive quantitative easing programs by the ECB which means the ECB is active in the financial markets buying billions of euro worth of eurozone bonds every month thus holding their prices up and yields down. The German bloc on the ECB council want to reduce or even stop this QE program but for the time being are being outvoted.

In theory the new banking union system and the proposed German plan are designed to “reduce the sovereign-bank nexus” by partially separating the two, preventing government debt crises spreading and taking down national banking systems. But the real problem, and why the German plan and the banking union could both make matters worse rather than better, is that so long as Germany and the EMU creditor states still refuse to accept the implications of monetary union (which is that some level of debt-pooling and fiscal union is imperative to hold the experiment together) all such measures merely further destabilise what is already a deeply flawed and inherently unstable system of monetary union. The German Council refuses to countenance any talk of an EU treasury or shared fiscal authority. The German consensus is that the only way to uphold monetary union is to impose strict control and reinforce existing rules with no transfers from the core to the periphery. If sustained this system can only impoverish the periphery countries leading to an eventual economic and political rupture in the single currency system

Almost eight years on, the eurozone nightmare continues. The flawed architecture of the currency union has delivered eight years of stagnation, mass unemployment and relentless austerity, and has failed to deliver stability.