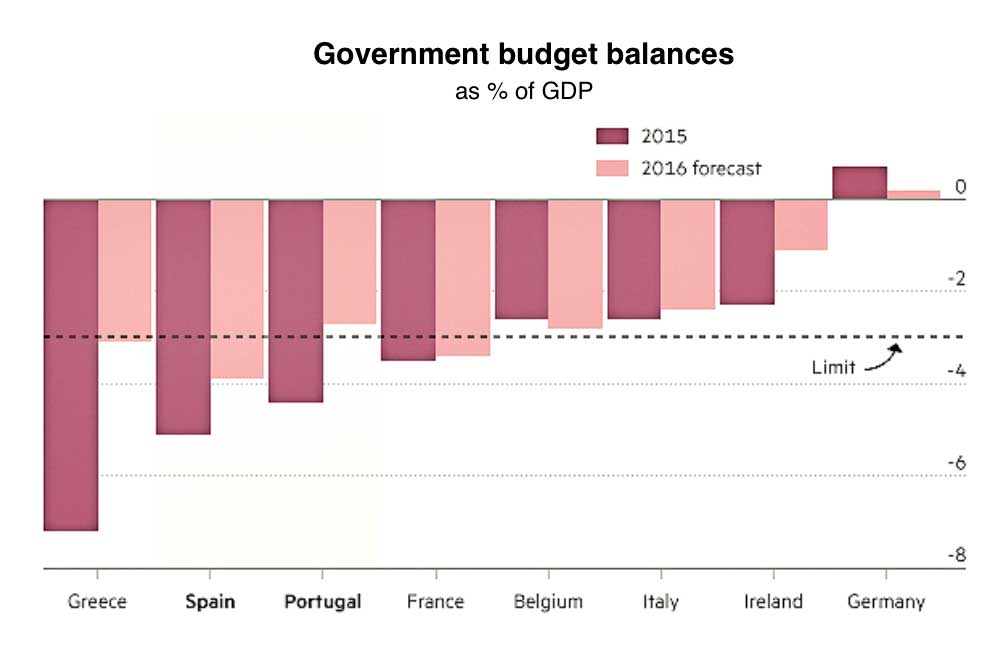

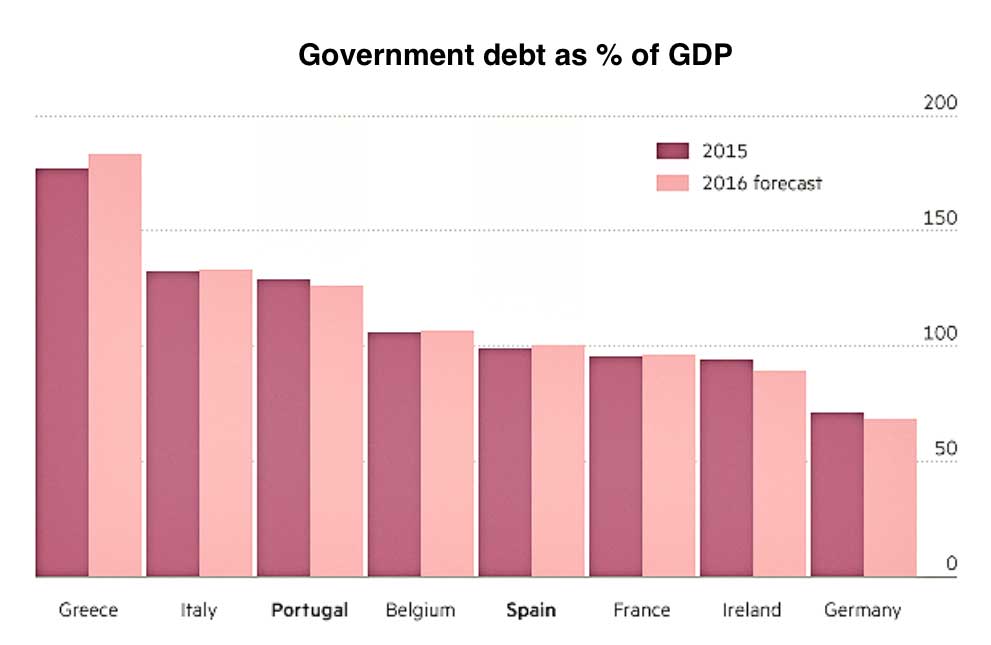

Most of the eurozone periphery, and even core members like France, are struggling to even get near the deficit reductions that under the eurozone system should in theory be mandatory. The current big worry is Italy because it is heavily in debt, still running a big deficit and has a very fragile banking system struggling with a mountain of bad debts. The concern is that if the financial markets were to decide that Italy was in real trouble it would push up yields in the Italian bond markets, making the management of Italian debt unsustainable and possibly triggering a wider crisis in the eurozone.

Brussels has decided to blink on deficit reduction, at least for the time being, and has granted Italy “unprecedented” flexibility in meeting EU debt reduction targets, using its political leeway to the full as it cautiously polices the eurozone’s fiscal rule book. Valdis Dombrovskis and Pierre Moscovici, the two European commissioners responsible for eurozone budget issues, said in a letter to Rome that “no other member state has requested nor received anything close to this unprecedented amount of flexibility”.

Zsolt Darvas of the Bruegel think-tank said that “if the rules were taken literally” Italy would be placed under the excessive deficit procedure. Overall the EU fiscal rules “have very low credibility”, he added. “Many countries are violating the rules almost constantly from one year to the next.”

After months of heavy lobbying from Matteo Renzi, the Italian premier, Rome secured most of the “budgetary flexibility” it sought, helping it avoid so-called excessive deficit procedures for failing to bring down its debt levels fast enough. Italy will be allowed extra fiscal room equivalent to 0.85 per cent of gross domestic product (or about €14bn) this year compared with the target mandated under EU budget rules. Such “flexibility” approaches the 0.9 per cent of GDP Italy demanded in drawn-out negotiations with Brussels.

Mr Renzi’s government is not completely in the clear, however. In exchange for the flexibility, the commission demanded a “clear and credible commitment” that Italy would respect its budget targets in 2017 to reduce the country’s high debt-to-GDP ratio, which stood at 132.7 per cent of GDP last year. In its letter, the EU said Italy should implement a deficit reduction programme worth at least 0.5 per cent in 2017 and 2018 to meet its targets, which next year is 0.15-0.2 percentage points more than Mr Renzi had planned. The gap must be closed in Italy’s autumn budget.

On Tuesday, Mr Renzi said the outcome was still “less than I would have wanted” but noted he had nonetheless struck a “significant agreement” with Brussels. “It’s not the solution to all evils but it affirms a principle: Europe is there when it comes to [budget] flexibility,” he said.

The commission had less wriggle room in assessments of Spain and Portugal. Economists found both took insufficient action and missed deficit targets, failings that put them on course for the first fiscal policy related fines since the creation of the single currency. The decision to offer Italy flexibility in relation to its deficit has sparked an intense debate within the commission over what critics see as its record of tolerating fiscal lapses by countries such as France, Italy and Spain. Some officials were on Tuesday pushing to delay parts of the package to avoid punishing Spain and Portugal before Spain’s election on June 26.

The need for the debate on timing shows the commission under Jean-Claude Juncker has acted as a self-described political body, even at the risk of undermining the credibility of the eurozone’s strengthened fiscal regime. But Mr Juncker in particular has been alive to Madrid’s concerns. As well as unease over penalising countries that have recently emerged from condition-heavy bailout programmes, commission officials feared that unveiling sanctions now would backfire in Spain, disrupt the June election campaign and give a leg-up to anti-austerity parties.

On Tuesday evening, officials were debating the option of delaying the negative fiscal decisions until after the Spanish elections, according to senior EU officials. Even if the commission went ahead, it would potentially signal that any sanctions (which can be up to 0.2 per cent of GDP) would likely be set at a low level and could be close to zero. The process to set specific fines takes several months and requires approval of EU finance ministers. For Spain, the 2015 deficit is estimated to have missed its target of 4.2 per cent of GDP (which itself would be a breach of eurozone rules) and that its deficit is now running as high 5.1 per cent. Spain is also on course to miss its target to bring its deficit below 3 per cent in 2016. Revised recommendations to bring their deficits under control are expected to give both countries a year to take action rather than the two requested, according to EU officials.

Portugal is also in under threat of a fine for failing to control its deficit in 2015. Its headline deficit was 4.4 per cent last year, 1.7 percentage points higher than its target. While the deficit was pushed up by the cost of winding up the failed bank Banif, the commission estimates that Portugal got lucky with “cyclical factors” that prevented its numbers being worse.