The troubles of the British steel industry, in fact the troubles of the entire global steel industry, are a direct result of the long term imbalances in the Chinese growth model. Those imbalances are now starting to unwind and the problems of the UK steel industry are just one of the many consequences of the Chinese economic adjustment that will be felt around the world and for many years to come.

The Chinese growth miracle was just a much larger and more persistent version of similar growth miracles that have occurred in the past (the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Brazil in the 1960s, etc). The sheer scale of the Chinese imbalances dwarfs previous similar episodes and it is plausible to expect that the consequent painful adjustment period that will follow once the growth model becomes exhausted might well be very large and very long lasting.

Like past growth miracle episodes the Chinese model involved the suppression of domestic consumption, high levels of investment (particularly investment in infrastructure), and high levels of debt, all orchestrated by the state. Essentially the Chinese model involved holding down domestic consumption, pegging the Yuan at a low level against the dollar in order to build a big trade surplus, and the flooding of the Chinese economy with very large quantities of very cheap capital to fund a very, very large investment program.

Not only was the Chinese scale of investment large but its rate of investment was also extraordinarily high, in fact the rate of investment in China as a proportion of GDP was the highest in history. It was the ramping up of this giant investment program after the crisis of 2008 that allowed China, and the emerging econiomies operating as part of its supply chain, to continue to grow after the crisis.

The Chinese growth model has reached its limits, in fact it reached its limits a while ago, and is now no longer sustainable. This is because during the early stages of an investment driven growth episode the investments being made are viable and can generate a return on capital (and on the debts incurred to fund them) but as the investment program continues there are fewer and fewer opportunities for viable healthy investment projects. Building a basic modern infrastructure using state sponsored cheap credit is probably a good idea that will pay off in terms of increased production and wealth, but once the essentials are in place what next? A six lane highway for every town and village? A giant airport in every small town? New cities built in the middle of nowhere where nobody wants (or can afford) to live?

The exhaustion of the growth model manifests itself as an ever increasing rate and quantity of bad debt inside the financial system, because more and more projects cannot generate a return that can be used to pay off the debts incurred to make the original investment, and as this debt grows, and is fed by ever more credit in a frantic attempt to sustain growth, it reaches the limits of what the system can absorb.

When the growth model ends there is a long period of painful adjustment. This adjustment takes many forms, including the painful deleveraging as the bad debt mountain is resolved, and it involves a very real change of production in the real economy. In order to move to an economy based much more on domestic consumption and much less on investment entire industries have to shrink and others have grow. This is not an easy transition and involves firms going bust (especially Chinese state owned enterprises), investors losing their money and tens of millions of people losing their jobs before there are new jobs available to them. And all this will have to happen in a non-democratic one-party society with all the rigidities that that implies, and of necessity will involve a significant loss of wealth for large parts of the Chinese elite.

The steel connection

The massive investment program means that China has been sucking in global commodities for its huge supply chain. That supply chain is now contracting, hence the unfolding economic crisis in many emerging economies. In order to implement its massive investment program China has been producing simply vast amounts of the key commodities required for its giant infrastructure program, that means staggering amounts of steel and cement for example. As the investment program starts to contract all that productive capacity for capital goods no longer has a market, and in the short term the only thing the Chinese capital goods sector can do is to try to export as much as possible, even if that means big price cuts and selling at a loss. The results are felt all over the world.

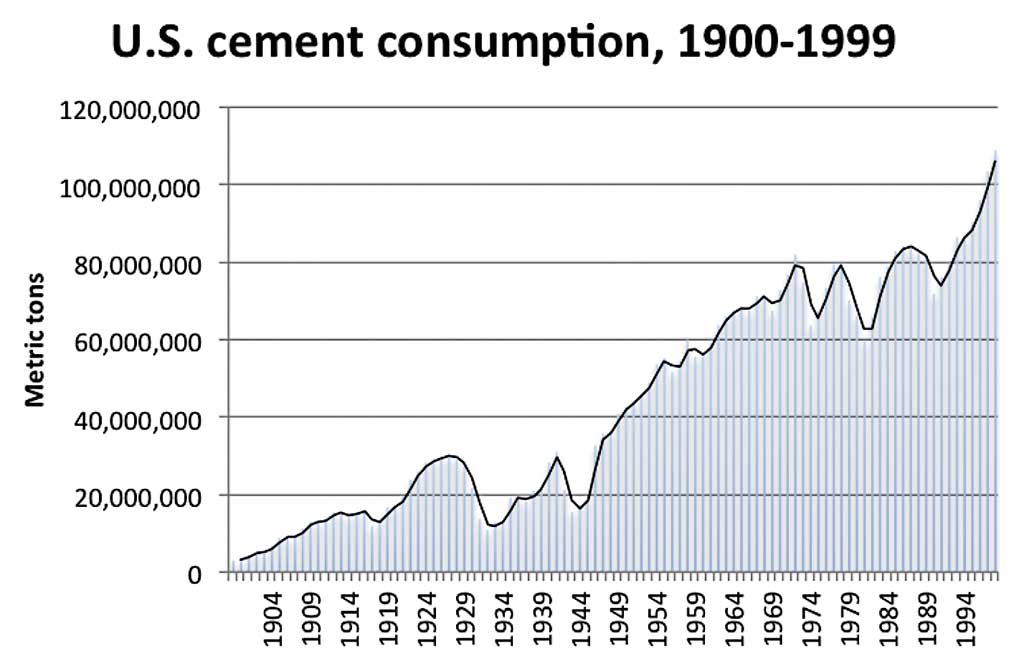

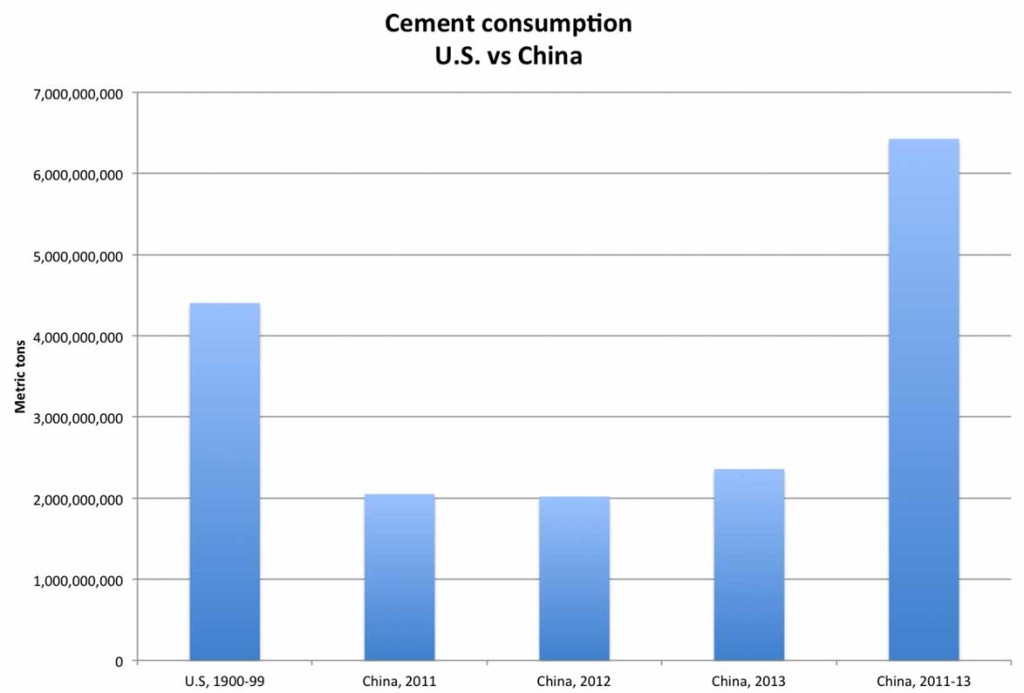

To get a sense of the scale involved consider that just between 2011 and 2013 China used more cement than the U.S. used in the entire 20th Century! This chart of US cement consumption shows how it tracks economic activity, including dips in construction during the Great Depression, World War II and the recession of the early 1980s. All of America’s cement consumption during the century adds up to around 4.4 gigatons (1 gigaton is roughly 1 billion metric tons).

In comparison, China used around 6.4 gigatons of cement in the three years of 2011, 2012 and 2013, as data in the chart below show. According to Hendrik van Oss, a mineral commodity specialist at the U.S. Geological Survey, China’s cement consumption between 2010–12 was about 140 percent of U.S. consumption for 1900–99.

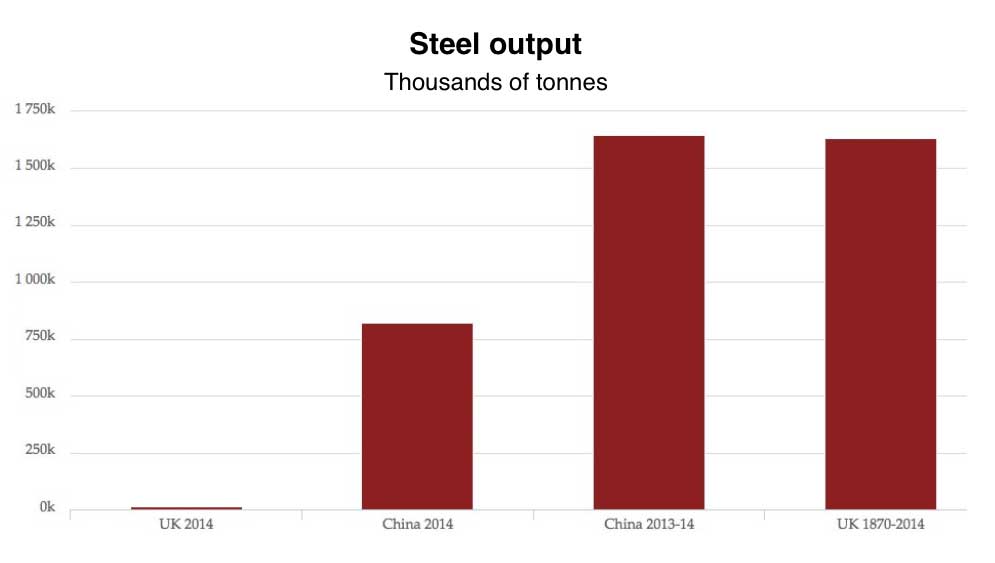

It is the same extraordinary story with steel. In the past two years alone China has produced more steel than the total cumulative output of the UK since the industrial revolution. At today’s rate of production, it would take 68 years for Britain to generate the steel China churns out of its mills in a single year.

Steel is, of course the critical ingredient in modern manufacturing and construction. If you are making something – anything – the chances you will need steel to make it with, whether that’s a car, a rail line, a can of food or a skyscraper.

And to start with, China was a positive story for Britain’s steel industry. As it expanded over recent decades it initially didn’t produce enough steel of its own to satisfy its seemingly limitless domestic appetite for steel and so it became an important destination for UK exports.

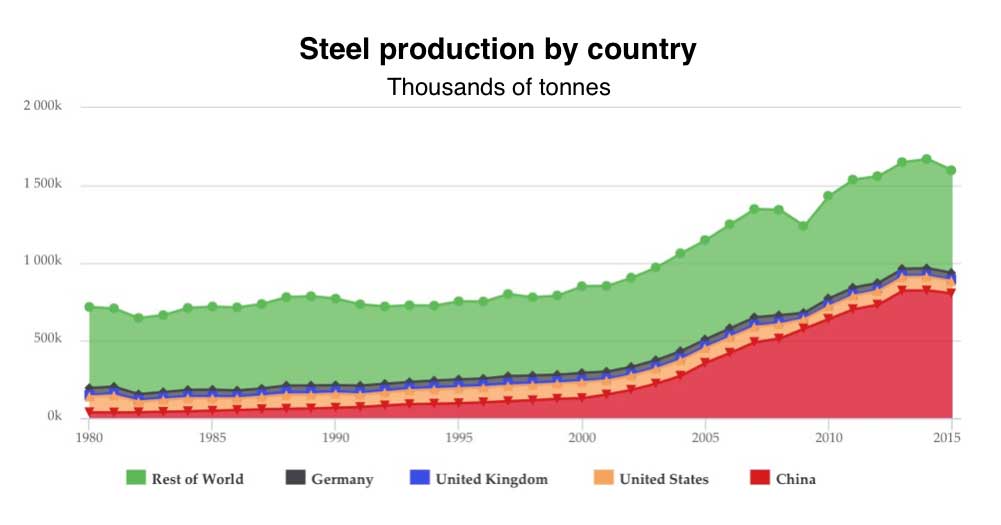

However, gradually the country has built its own steel industry, and because it was part of the biggest investment program in history the Chinese steel industry has also become enormous. Since 1980 China has gone from producing 5% of the world’s steel to making more than half of it – just over 800m tonnes.

Now, with Chinese demand tailing off as a result of its investment led growth model reaching exhaustion, that steel needs somewhere to go, and where it’s going is everywhere. The Chinese has been “dumping” that excess steel on global markets, selling it for less than it costs to make. As a result, the global steel price has collapsed in recent years, wiping out margins for UK steel manufacturers and contributing to the industry’s recent problems. Making matters worse is the fact that thanks to the ridiculous EU emission rules, UK steelmakers face punitive energy costs. For an industry which cannot compete on price (even if some of the UK’s steel products are of a higher quality than many other producers) the inevitable result is closure.

Like all other examples of over production, mal-investment, credit bubbles and other imbalances, the Chinese imbalances will eventually unwind, and individual problems resulting from the imbalance and its rectification, such as a global steel glut, will be resolved. China is already starting to cut back its steel production. Last year Chinese steel output fell for the first time in a quarter of a century. Indeed, hopes that this reversal could continue have pushed the steel price higher in recent months, helping to repair margins. The EU is also pushing ahead with anti-dumping measures, increasing tariffs on steel imports from China although, say critics, nowhere near enough to offset the impact of China’s influx.

Whether a rebalancing of the global steel production and markets will come in time to save the UK steel industry is not clear, and probably unlikely. Over the past half century the industry has become a kind of economic football, nationalised by Labour in 1949, privatised by the Conservatives in 1952, nationalised by Labour in 1967, privatised by the Conservatives in 1987. So what happens next is anyone’s guess – though one would presume the Tories would be reluctant to do what Labour have done repeatedly and plough on with a nationalisation, temporary or otherwise.

The Chinese steel industry will shrink and the global steel markets will rebalance, albeit after some very painful adjustment. Its worth remembering that a few decades ago the world’s steel market like today was comfortably dominated by one giant which produced about double what the US, the next biggest contender, did. That giant was the Soviet Union. After the collapse of communism, so did its steel output, leaving more room for everyone else to compete. Nevertheless the economic future for steel production is unpredictable, not least because the capital goods sector always experiences exaggerated version of business cycles, recessions and adjustments. So with the world economy still experiencing structural problems nearly ten years after the finical crisis the global steel markets will probably not stabilise for some time.