The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear

Antonio Gramsci

Politics is going through an odd phase. Things seem to be changing in some profound ways and yet the old institutional configurations seem to linger on, weaker but not yet dead. The remark of Gramsci quoted above has never seemed more appropriate. In the UK it feels very much like all the old certainties are unravelling and that the broad consensus established by Thatcher, and which had replaced the preceding post war ‘Butskellist’ consensus, is finally cracking. While English politics now seems more polarised around a two party system than at any time since the early 1960s, with support for both the Tories and for Labour running at almost record high levels, at the same time there is a strong sense that the depth of support for Labour and the Tories is quite shallow and fickle, with much weaker tribal loyalties. There is also an all pervading sense of people being fed up that so much in public life seems so dysfunctional. At the same time Scottish politics seems to have sheered away completely from English politics with the SNP seemingly safely ensconced in power and, now that the possibility of actual independence has receded, happily ruling as a more or less competent, and non-corrupt, centrist coalition which whenever it wants to inject a bit of fizz into its supporters can wave the nationalist flag (a bit like the way ‘socialism’ functions on the Left).

Looming above everything in the UK is the issue of Brexit and the tortuous process of a minority government negotiating a deal. Given the very deep fractures in the Tory party over Brexit and given their weak parliamentary position as a minority administration it is curious and disappointing that Labour seem so incapable of making mischief on a bigger scale on the issue, and utterly incapable of even thinking about building a cross party parliamentary bloc to push through a good Brexit deal (let alone to stop Brexit).

So whats going on under the hood?

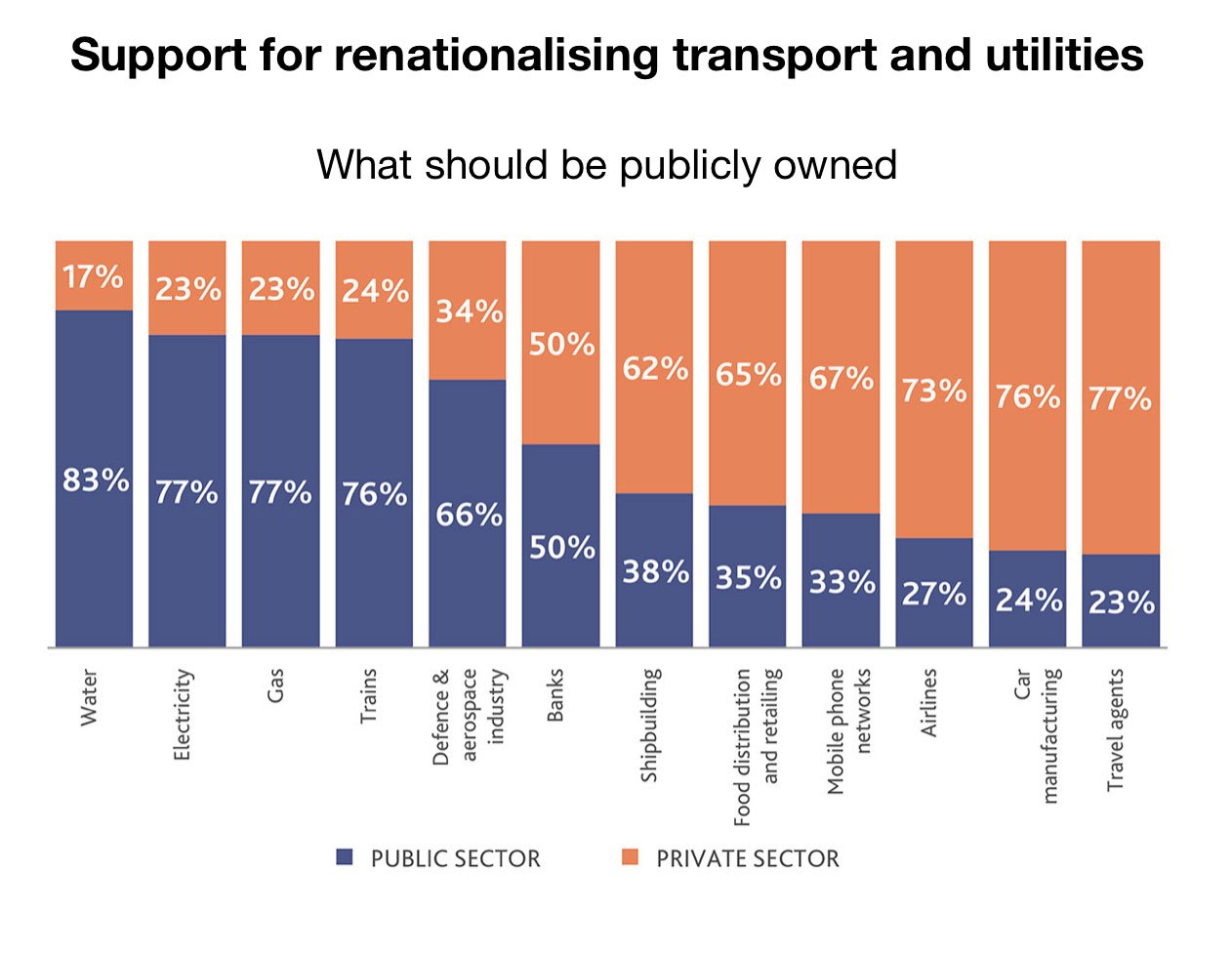

The ‘Overton window’—the range of ideas that the public will accept and which a politician can therefore voice—has clearly shifted. Brexit was considered inconceivable only a decade ago. So too was the prospect of a Labour leader advancing in the polls by advocating the nationalisation of railways, water and energy.

Matthew Elliott and James Kanagasooriam have written an interesting, and at times eye opening, analysis of the shifting base lines of public opinion in the UK entitled “Public opinion in the post-Brexit era: Economic attitudes in modern Britain”.

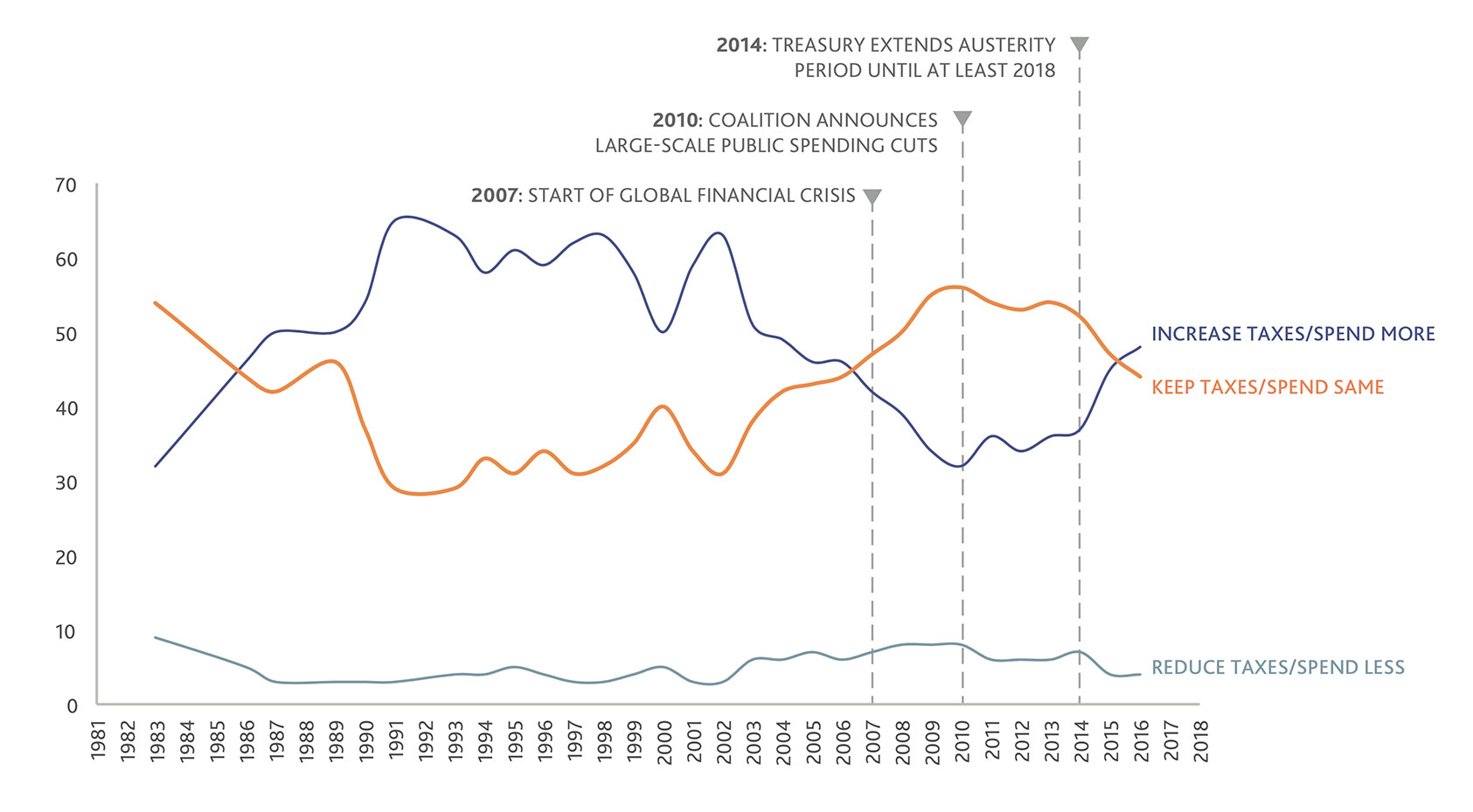

This chart from the report shows the key shifts. First in the immediate aftermath of the 2007-8 financial crisis there was a strong shift against public spending and then from 2014 a strong shift back to supporting increasing taxes and spending.

Even more startling is the dramatic shift in public opinion in favour of taking some key sectors back into public ownership. In particular there is now very strong support for reversing the privatisations of Water, Electricity, Gas and the Railways, essentially the sectors that were privatised in the late hubris phase of Thatcherism and where privatisation has clearly not led to a better deal for consumers (unlike say Telecoms).

And yet for all this apparent shift to the ‘Left’ in public opinion the Labour Party seems so far incapable of breaking out into a clear, large and commanding lead in the polls. One of the things that is happening is that the apparent return of the two party system is masking a much more complicated breakdown of public opinion into complex new patterns which do not fit comfortably into the old Left-Right party spectrum. As a result both parties, and politically engaged people on the Left rooted in the old political spectrum, find the contours of modern public opinion deeply confusing, and as a result policies and strategies misfire and we get seismic events like the Brexit vote.

Traditionally there was a simple single axis set of two-party positions; for the Conservative voters, right-wing on economic issues and socially conservative on cultural issues, for Labour voters, the opposite (although on the Labour side there was always greater social conservatism than was acknowledged). What is confusing both the major parties is that there is now also a significant chunk of voters, containing both Labour and Conservative voters, arranged on a new axis who are strongly left-wing on economic issues yet more conservative on cultural questions.

The table below shows an example of the new strange contours of politics in England. It seems that on traditional questions concerning the ‘old’ issues of economics, the sort of issues that used to define the political spectrum in the UK, that UKIP supporters are marginally to the left of Labour supporters.

| Attitudes to inequality by party identification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage who agree | UKIP Supporters | Conservative Supporters | Labour Supporters | All |

| There is one law for the rich and one for the poor | 76 | 39 | 71 | 59 |

| Ordinary people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth | 76 | 41 | 72 | 60 |

| Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance | 72 | 41 | 60 | 53 |

| Big business benefits owners at the expense of workers | 62 | 39 | 63 | 53 |

| Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well paid | 40 | 22 | 52 | 39 |

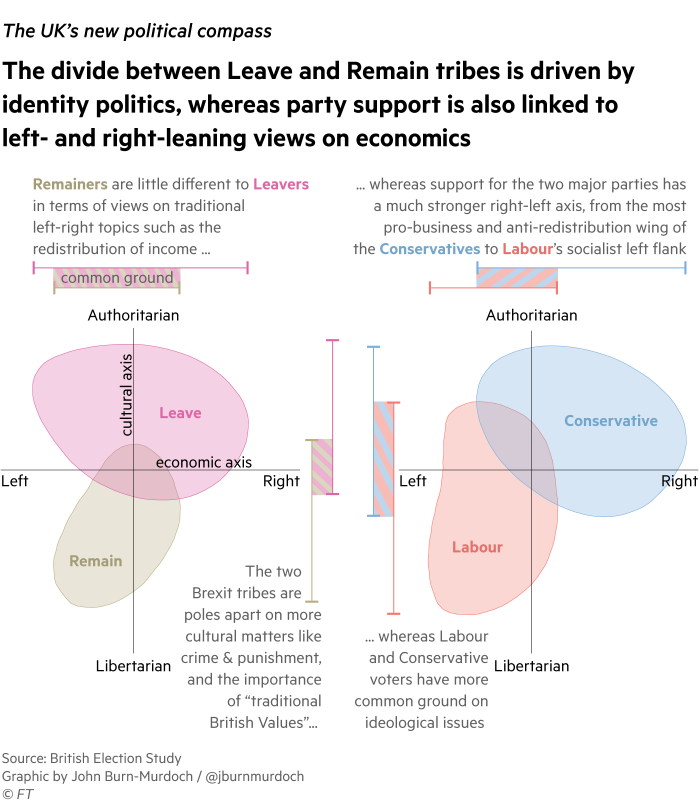

The FT recently published this interesting chart based on data from the British Election Study.

The interesting thing to note is the cluster of voters in the top left quadrant, to the ‘Left’ on economics but to the ‘Right’ on social issues, who are not really represented by anyone. These voters are predominantly working class.

Most parliamentary candidates from the major parties fit into the classic party positions. Plotted on a similar scale, their stated positions would show the Labour candidates falling into the bottom left quadrant, economically left and socially liberal, while the Conservative candidates clustered towards the top right quadrant, economically right and socially conservative,

In the last thirty years, the era of so called Neo-Liberalism, the range of policies that were deemed to be politically acceptable by pretty much the entire political and media elites, moved towards the bottom right. It almost amounted to a sort of trade off: tolerance for diversity, minority rights and discrimination laws balanced by privatisation, deregulation and tax cuts. This meant that policies that were still very popular with sizeable groups of voters, especially working class voters, were no longer on the political agenda of any party. Policies such as renationalisation and high taxes on the rich, the restoration of capital punishment and cuts to immigration were utterly marginalised along with the politicians who espoused them. The effect was to take a whole series of policies, that were actually quite popular, off the political agenda, and increasingly it meant that a sizeable constituency developed of people who felt essentially unrepresented by any mainstream party.

As American political scientist Alan Wolfe said:

“The right won the economic war, the left won the cultural war”

Or, as David Goodhart put it in his excellent recent book “The Road to Somewhere: The New Tribes Shaping British Politics”, the two liberalisms won, the economic liberalism of the right and the social liberalism of the left:

What if a lot of people feel that there’s no point in voting because whoever you vote for you get the same old mix of economic liberalism and social liberalism – Margaret Thatcher tempered by Roy Jenkins.

The two liberalisms – the 1960s (social) and 1980s (economic) – have dominated politics for a generation.

It’s true that during the early ‘Jacobin’ phase of the Thatcherite hegemony the Tories sent out lots of socially conservative messages (on law and order, rolling back tolerance of homosexuality, coded and occasionally explicit expressions of concern about race and immigration) but in reality the long rule of the Tories from 1979 to 1997 actually delivered very little. Tory politicians did very little about rolling back liberal policies initiated during the 1960s, and the social changes that went with them. There may have been a lot of angry denunciations by Conservative politicians of ‘political correctness’ but they didn’t do much about it. For example by the time of the John Major premiership racist and sexist language that would have passed unremarked in 1979 was considered unacceptable. Although there was a continuing embrace of public anxiety about immigration the Tories actually did very little to restrict it, and they didn’t even contemplate implementing socially conservative policies, such as the reintroduction of capital punishment, which would have been hugely popular with their voters and the public at large.

What the Tories really delivered of course was a very radical and right wing economic program.Voters might have thought they were voting for socially conservative policies but what they got was economic liberalism.

Meanwhile the left, having suffered a series of catastrophic defeats between1979 and 1987 pretty much abandoned economic leftism and instead became increasingly focussed on social issues, a terrain where seemingly battles could actually be won. New Labour was the Left’s project that enthusiastically embraced this apparent new political reality, made it it’s own and triumphantly broke the Tories hold on power by becoming electorally very successful. New Labour pumped money back into the public sector and tried to mitigate the rise in economic inequality by using redistributive taxes and benefits while advancing its socially liberal agenda but it also accepted accepted privatisation and de-regulation. Its Equality Act in 2010 said very little about economic equality.

So the story of UK politics from the late 1970s to the election of Jeremy Corbyn as party leader in 2015 was of the right quietly abandoning the culture war and the left doing something similar with the economic war.

All of which meant that politics began to drift away from some working class voters. Voters who were socially liberal or economically on the right got at least some of that they wanted. Those in the top left quadrant of the diagram above, strongly to the left on economic policy and strongly socially conservative, were quietly ignored.

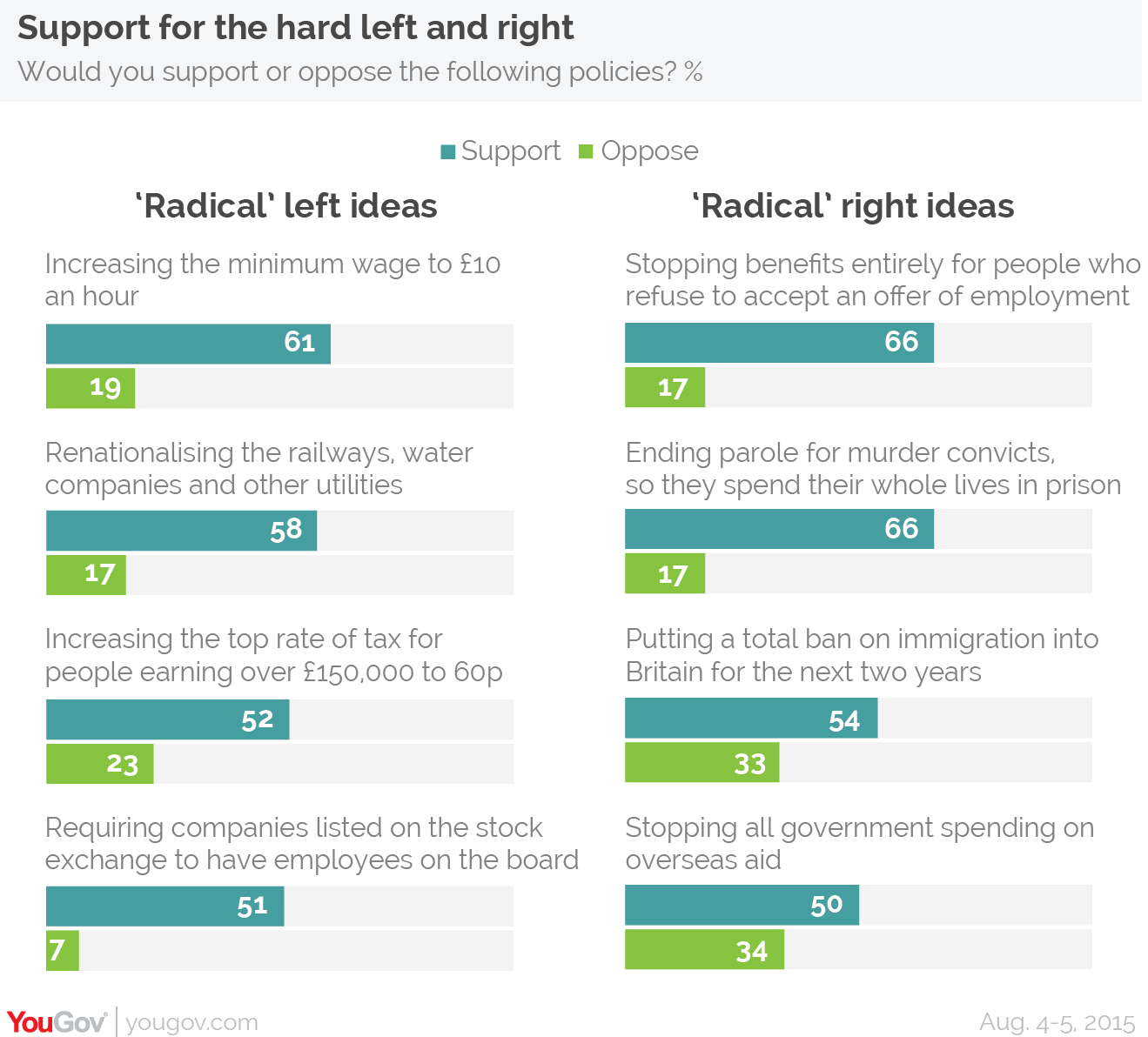

A YouGov poll in 2015 found majority support for both “radical left” and “radical right” policies. As the diagram below shows that support was quite strong for policies portrayed as bonkers by the mainstream parties and the political class. Part of the problem for the political class and the media is that this constituency of supporters of radical policies just don’t fit into the old Left-Right spectrum, they were both Left and Right at the same time. And they were pretty pissed off.

The YouGov survey also found that all policies except for workers on boards had majority support among UKIP voters. Perhaps more surprisingly, between 40 and 50 percent of Conservative voters backed the ‘radical left’ policies and a majority of Labour voters were in favour of the suggestions on benefit cuts and ending parole for murderers.

The accompanying commentary said:

All of this points to a contemporary mindset that defies traditional classification. It is possible for the same people to believe several things at the same time which come from opposite ends of the traditional ‘political spectrum’.

Most tellingly, although 63% of British people are at least fairly clear on what is meant by the left/right terms, the largest group (43%) say they don’t think of their views as being right or left wing.

I grew up in the London working class, a social group who have seen the entire social, ethnic, cultural and economic life of their home town completely and utterly transformed, a group that went from being the strongly majority culture to being a strongly minority culture, and yet who have on the whole responded with a surprising degree of tolerance and acceptance. The people I grew up with would not have found anything in the YouGov survey to be surprising. They strongly believed in nationalisation, workers’ rights and the welfare state, while also having a low opinion of ‘shirkers’ and a generalised disdain (mistrust even) of foreigners, they were relaxed about being strongly patriotic, proud of being English, and strong supporters of the monarchy. They may have thought that all coppers were bastards but they also thought that murderers should be hanged. Interestingly the late trade unionist Bob Crow came from this tradition, strongly and militantly to the left on economic issues but he was also a supporter of capital punishment.

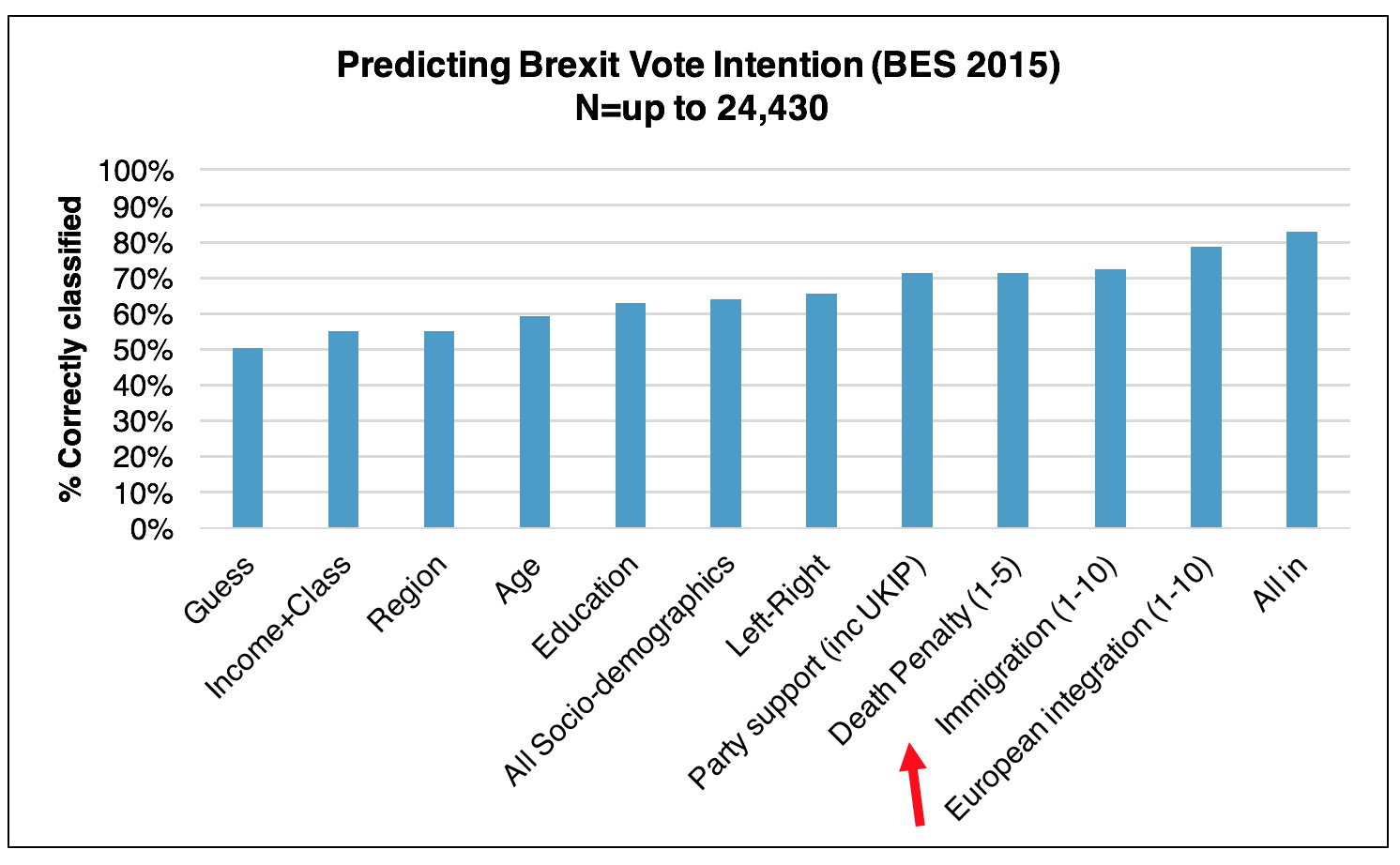

Eric Kaufmann wrote an interesting article entitled “It’s NOT the economy, stupid: Brexit as a story of personal values” which included this interesting chart:

Kaufmann wrote this commentary on the data in the chart above:

“Let’s therefore look at individuals: what the survey data tell us about why people voted Brexit. Imagine you have a thousand British voters and must determine which way they voted. Figure 2 shows that if you guess, knowing nothing about them, you’ll get 50 percent right on average. Armed with information on region or their economic situation – income and social grade – your hit rate improves to about 54 percent, not much better than chance. In other words, the big stories about haves versus have-nots, or London versus the regions, are less important.

Age or education, which are tied more strongly to identity, get you over 60 percent. Ethnicity is important but tricky: minorities are much less likely to have voted Leave, but this tells us nothing about the White British majority so doesn’t improve our overall predictive power much.

Invisible attitudes are more powerful than group categories. If we know whether someone supports UKIP, Labour or some other party, we increase our score to over 70 percent. The same is true for a person’s immigration attitudes. Knowing whether someone thinks European unification has gone too far takes us close to 80 percent accuracy. But then, this is pretty much the same as asking about Brexit, minus a bit of risk appetite.

For me, what really stands out about figure 2 is the importance of support for the death penalty. Nobody has been out campaigning on this issue, yet it strongly correlates with Brexit voting intention. This speaks to a deeper personality dimension which social psychologists like Bob Altemeyer – unfortunately in my view – dub Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA). A less judgmental way of thinking about RWA is order versus openness. The order-openness divide is emerging as the key political cleavage, overshadowing the left-right economic dimension. This was noticed as early as the mid-1970s by Daniel Bell, but has become more pronounced as the aging West’s ethnic transformation has accelerated.”

Putting it all together

So what seems to be happening is that the old Left-Right divide has broken down in ways that surprise and perplex the old political parties. The people have become awkward, they just won’t fit into those nice neat political pigeon holes anymore. What is happening in the UK is to a significant degree part of what is happening across the EU (and in Trump’s USA) which is a rebellion against the way things are but a rebellion that does not fit comfortably into the old political categories. Yes it is a rebellion against the economic costs of ’Neo-Liberalism’, against the insecurity of zero hours contracts and stagnant wages, so it is a rebellion that wants the government to do more. But is also a rebellion that wants the government to do more about immigration and crime. The common theme emerging here is that people want the government to do more. Whether it’s about crime and immigration or stopping profiteering and ensuring greater economic equality, the underlying theme in all of this is a desire for more government action.

This desire for the government to do something is, in my opinion, strongly tangled up with the issue of the the erosion of the national state, of national government and of national identity, in a modern globalised world. The unrepresented people of the upper left quadrant of the earlier diagram, those on the left economically but who also crave socially conservative order, think about all this through ideas and values about place, belonging, and entitlement. About what belongs to them and what their rights should be, about their country, their government, about who is on the inside and who is coming from the outside.

In Europe the decision to push the European project down the path of ‘ever deeper union’ starting with monetary union has dangerously exacerbated all these currents of tension and discontent. In the EU people are told they cannot control their borders, they cannot determine who to let into their national community and who to shut out. In the EU there is less and less chance for any single national government (who longer issue its own currency) to make its own economic policy or regulate its own national markets. For those who feel less and less represented by the old parties, because none offer a program for a strong activist government delivering economic leftism with a socially conservative agenda, the EU often seems just another way to reduce the power of ‘their’ national government, another way to stop the government of ‘their’ country from doing what they want. For many the EU seems to be a big reason, maybe the main reason, their government can do so little. Hence the rise of of the populist nationalists and Brexit, which are all about the desire to ‘take back control’, to get a national government who will actually act strongly in the interests of the nation. Hence also the decline of social democratic parties who won’t offer social conservatism and refuse to offer economic leftism, and who generally embrace the EU and the deliberate erosion of the power of nation states and national governments as a good thing.

In the UK this all leaves the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn in a bit of a quandary. Its strong commitment to an activist economic leftism, which is so easy and comfortable for traditional leftists, means it did quite well in the last election because as the data in the surveys mentioned above shows there is actually strong support for policies like renationalising the privatised utilities and the railways. But Labour didn’t win the election, and in order to really remake the country Labour needs to win and win well. And that means Labour needs to reach out to the people of the upper left quadrant, the socially conservative voters who support economic leftism but who also voted for Brexit, who want the government to reassert control over the borders and to reduce immigration. Voters who actually want quite a lot of things that most Labour Party members would feel uncomfortable about and sometimes view as downright repellant. Labour has do this whilst still adjusting to having been driven back by the rise of the SNP (yet another movement articulating popular discontents via the discourse of empowering the nation) into being for the first time in its history an English as opposed to a British party. That means that Labour needs a vision of what being English is all about, it needs to start thinking about what England is and should become.

Labour’s most pressing problem is what to do about Brexit. Its leadership is aware, I think, of some of the new contours of politics I have been writing about, at least in so far as it affects the tactical calculations around its policy on Brexit. But mostly I sense the calculations of the leadership are about not losing its existing electoral support from Brexit supporters by endorsing things like membership of the Single Market. This has led to what might be called Labour’s ‘quietist’ approach on Brexit, of not saying too much or anything too specific, playing for time, and leaving the Tories to fight it out amongst themselves. This does mean abandoning the opportunity to take the leadership of a House of Commons which almost certainly has a clear majority for the softest sort of Brexit, and it means not supporting a second referendum. As the reality of Brexit approaches, an event likely to lead to some sort of generalised political crisis, Labour will be forced off the fence and it should be doing more to prepare its constituency of voters for the compromises to come.

In terms of Labour’s longer term ability to win an election, I don’t get a sense that the leadership has really begun to think through how it can square its deep commitment to socially progressive positions with policies that can attract the socially conservative voters its needs in order to win a big majority. Labour’s response has been to strongly push its program of economic leftism which it knows has already helped it to increase its popularity but I am not sure that more of the same on the economic front is going to help it win over the new voters it needs. The danger is that some force on the right, perhaps a rejuvenated post-Brexit Tory Party recovered from the Brexit trauma, could find a way to package some lefty economic populism with a whole lot of social conservatism (especially around immigration) and thus cut the ground from under Labour. I think that’s partly what May wanted to do with her embryonic ideas about what might have been the ‘New Tory Party’, but a horribly bodged campaign in an unnecessary election, and the surprising surge of support for Labours economic leftism, produced a crucial electoral setback and the collapse of May’s project to remake the Tory party. That doesn’t mean that once the Brexit dust has settled someone else won’t remake the Tory party along similar lines.

There is still a lot of unoccupied ground on the new political terrain. It won’t stay unoccupied forever.