China is struggling to rebalance its economy, to move from the exhausted super high investment low consumption model of the ‘economic miracle’ to a more balanced economy based much more on domestic consumption. That is a lot harder to do than it sounds, especially if you are a deeply corrupt elite ruling through a rigid and authoritarian political system that leaves you with few political shock absorbers. The consequences of the Chinese slow down have already been felt around the world, especially in the shape of collapsing commodity prices (most notably oil prices) and falling growth and economic crises in the Chinese international supply chain amongst the emerging economies.

In recent weeks there has been much talk of the Chinese slow down stabilising, that the old high growth model could and would continue to deliver growth above 6% and that China was avoiding the feared ‘hard landing’. The world’s financial leaders met recently in Washington and having started this year worried about China’s decelerating economy dragging the world into another major crisis, they suddenly started to ooze optimism about China

The gathering of the IMF, World Bank, Finance ministers, central bankers and other top officials gathered in Washington seemed to agree that Beijing’s moves to stabilise its economy had temporarily eased global fears tied to the world’s No. 2 economy.

“There was not the same level of anxiety,” said International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde.

“There’s a lot more comfort now in the ability of China to keep demand at a certain level that would foster growth,” Mexico’s Finance Minister Luis Videgaray said in an interview.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew said a new set of policies unveiled by China’s National People’s Congress last month “addressed some of the core issues, including the very significant challenge of dealing with excess capacity in their economy. There was a broad sense that the policies announced are important, and there’s a broad hope that those policies will be implemented effectively and quickly”.

The IMF remains cautiously optimistic about China’s economic outlook. It recently upgraded China’s growth forecast for this year by 0.2 percentage point to 6.5% but said Beijing’s plans to boost output and overhaul its economy aren’t sufficient to address long-term growth concerns. IMF officials acknowledged much of Beijing’s stimulus would likely take the form of more credit growth, particularly support for inefficient sectors.

In an interview, Chinese Finance Minister Lou Jiwei defended China’s efforts, saying the country had made progress in correcting “big distortions” in its economic system. He pointed to measures aimed at reining in off-budget borrowing by local governments, attempts to cut red tape for businesses, and steps to give the market a bigger say in pricing agricultural and other products.

“When the outside world looks at China, they often think reforms are not proceeding as fast as expected,” Mr. Lou said. “But they don’t know that distortions are entrenched in our economic system.”

Whats really going on?

“Sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Chinese state statistics about the economy are notoriously inaccurate as they are massaged and altered in order to sustain the public line which is that the high growth is continuing and everything is under control. In order to try to understand what is really happening inside the Chinese economy it is better to look at data that appears more robust and reliable than the state announced GDP figures.

Rail freight volumes are a very good indicator of China’s goods-producing and goods consuming economy, not just manufacturing, construction, agriculture, and the like, but also consumer goods. Thus they’re also an indication of consumer spending on goods. What has been happening is that rail freight volume is collapsing: the first quarter this year puts volume for the whole year on track to revisit levels not seen since 2007.

While China’s economy was strong, rail freight volumes were soaring. For example, in 2010, when China was pump-priming its economy with its stupendous investment program, rail freight volume jumped 10.8% from a year earlier. In 2011, it rose 6.9%. It had soared 44% from 2005 to 2011! But 2011 was the peak.

In 2012, volume in trillion ton-kilometers declined one notch and in 2013 stagnated. But in 2014, volume dropped 5.8%. And in 2015, volume plunged 10.5% to 3.4 billion tons, according to Caixin, citing figures from the National Railway Administration. It was the largest annual decline ever booked in China.

The People’s Daily, the official paper of the Communist Party, described the 2015 economic situation thus: “Dragged by a housing slowdown, softening domestic demand, and unsteady exports, China’s economy expanded 6.9% year on year in 2015, the weakest reading in around a quarter of a century.”

How does this make sense? Rail freight volume plunges 10.5% in 2015, and the economy still increases 6.9%? Is that plausible?

At the time China’s central planners aimed to increase rail freight volumes to 4.2 billion tons by 2020. This would assume an average annual rail freight growth rate of 4.3%. So these real world declines are not part of the planned transition to a consumption based economy. They’re totally against that plan or any other plan.

But then in the first quarter of 2016 things got a whole lot worse. Rail freight volume plunged 9.4% year-over-year to 788 million tons, according to data from China Railway Corporation, cited by the People’s Daily. At this rate, rail freight volume for 2016 will be down 20% from 2014, which had already been a down year, and the volume in 2016 will end up where it had been in 2007.

The World Bank says that China’s economy would grow 6.7% in 2016, the IMF pegs it at 6.5%, both estimates are based on the dubious GDP statistics issued by the Chinese government. This literally does not make sense, and could only be true if in 2016, after falling 10% in 2015, rail freight plunges by another 10% or so while economic growth soars to nearly 7% – a rate that would make China one of the fastest growing economies in the world. So something doesn’t add up here.

The Chinese debt bubble continues to inflate

The Chinese growth miracle has been founded upon flooding the economy with state sponsored super cheap and super abundant capital in order to promote an investment level never before seen in history. As a result China has changed in a truly spectacular fashion as infrastructure of all sorts, high speed rail lines, highways, airports and numerous entire cities, have sprouted across the country. Meanwhile the share of Chinese GDP going to personal consumption has been one of the lowest percentages seen in any economy ever. The problem with these sort of investment heavy ‘growth miracles’, and there have several such ‘miracles’ in the last century, is that eventually the opportunity for further productive investment (i.e investments that at a minimum can generate returns that will enable the repayment of the money borrowed to implement them) simply runs out. A point is reached when a large, and growing, proportion of the investments are unproductive. During the latter stages of a growth miracle, investment and credit creation can power along seemingly as strong as ever but the ever increasing proportion of unproductive investments manifests as a growing quantity of bad debt inside the financial system. At some point the limits of the system are reached and the investment programs and credit creation that have fed the growth miracle shudders to a close, often in the shape of a financial and economic crisis, and is most typically followed by years, or even decades, of much slower growth.

In order for China to reshape its economy on a new and more sustainable footing it needs to drastically reduce investment levels, drastically reduce the credit creation that was supplying the cheap capital for the investment program, drastically increase the rate of personal consumption as a proportion of GDP. This means among other things that insolvent enterprises (especially the giant state owned enterprises which are particularly dependent on continuous inflows of more or less free capital) must be allowed to go bust, entire industries that are dependent on the giant investment program (such as construction, steel, cement etc) must shrink drastically and the personal consumption goods sector must increase significantly. And of course this needs to be done in a way that minimises social disruption, avoids a surge in unemployment (which would in itself undermine the transition to a consumption based economy) and somehow prevent a rebellion of those sections of the elite whose interests are tied to the old system. Tricky.

What seems to have happened in the last few months in China is that the leadership has taken fright at the prospect of a hard landing for the economy and rather than tightening the cheap credit pipeline to slow the rate of investment has actually opened the taps and unleashed yet another wave of credit and debt creation. That means they have done exactly the opposite to what is required in order to engineered the economic transition. And it is this new round of almost frantic credit creation that has been (mistakenly) interpreted as good news by many commentators. In fact this new round of credit creation can only make matters worse and make the coming adjustment even more wrenching.

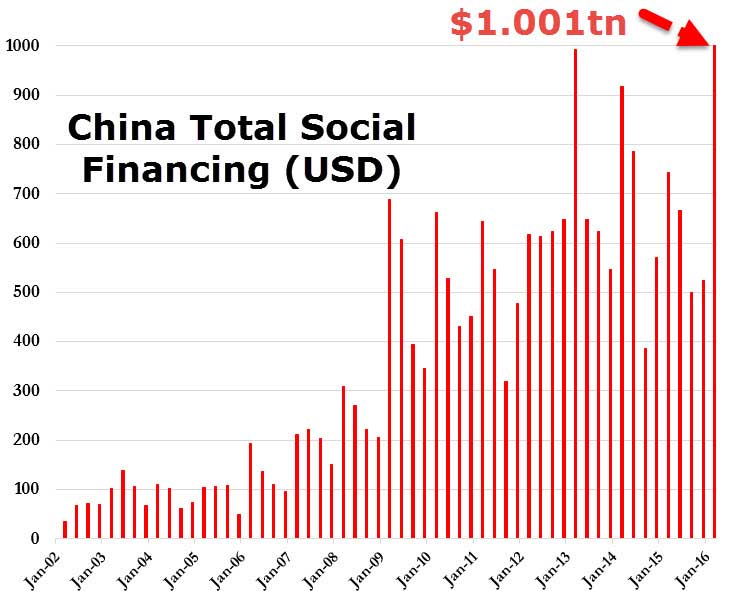

A good measure for estimating the amount of credit (and debt) being created in the system in China is the so called “total social financing” (TSF) which is a liquidity measurement tool invented by Beijing in 2011, as is viewed as being a better indicator of monetary policy than traditional measures of money supply. It was created to help Chinese leaders keep tabs on fundraising as the financial system diversified away from state-controlled policy lending. The TSF is an economic barometer that sums up total fundraising by Chinese non-state entities, including individuals and non-financial corporates. The TSF measures money offered by domestic suppliers, mainly by financial institutions, but also by Chinese households and non-financial entities. As such, it offers a view of both borrowers and lenders.

The first quarter of 2016 witnessed record Chinese credit expansion and in January there was an incredible increase of $520 billion in social financing, and then after a lull in February in March there was another expansion of $360 billion. This means that in the first quarter of 2016 there was a staggering one trillion dollars in overall the total credit expansion. Not long ago Chinese officials had set their sights on reining in rampant credit growth. Having clearly reversed course, credit expanded during the quarter at a blistering almost 20%. This compares to its recent official target of 13% and China’s GDP target of 6.5-7.0%. Keep in mind that Chinese system credit (“total social financing”) surged 12.4% in 2015, or almost $2.4 trillion, a massive amount of credit but it was still insufficient to levitate global energy and commodity prices. If the total debt in the credit system in China is added up, including the shadow banking sector, it looks as if the the total debt/ to GDP ratio could be as high as 350%.

The Peoples Bank of China also reported that the broad M2 money supply measure grew 13.4% in March from a year earlier, or precisely double the rate of growth of GDP. This means that even if the reported high rate of GDP is accurate it still took two dollars in new loans to create one dollar of GDP growth. That is clearly not sustainable and sometime in the near future the credit expansion will come to an and then growth will crash just as debt peaks.

Billionaire investor George Soros has warned that a surge in China’s debt is bringing the world’s second-largest economy on the brink of a financial crisis similar to one the U.S. faced in 2008.

“There is an eerie resemblance to what’s happening in China to what’s happened here leading up to the financial crisis in 2007-2008 and it is similarly fueled by credit growth,” Soros said at a round table hosted by Asia Society last week. “It’s eventually unsustainable. But it feeds on itself and it has a lot to do with real estate,” he said.

Soros earlier this year attracted Beijing’s ire by predicting that a hard landing in China is inevitable. The government responded to the famed investor’s dire forecast by attacking him in a newspaper editorial, “Declaring war on China’s currency”.

When you borrow too much money it always goes the same way: good times while you’re spending the proceeds and a nightmare when your creditors demand repayment. For 40 years the world has been repeating the same cycle and for all that time the markets have been enthused by the first stage, only to be crushed by the second.