The IMF formally announced on January 29th that it changed the policy of exceptional access criteria, in essence reversing a highly political decision of the Fund back in 2010, a decision that saved the euro and paved the way for half a decade of economic devastation that has impoverished the Greek people.

In the statement the IMF says:

“The broad objectives of the reform—which includes the removal of the “systemic exemption” that was created in 2010—is to help promote more efficient resolution of sovereign debt problems and avoid unnecessary costs for the member, its creditors, and the overall system.”

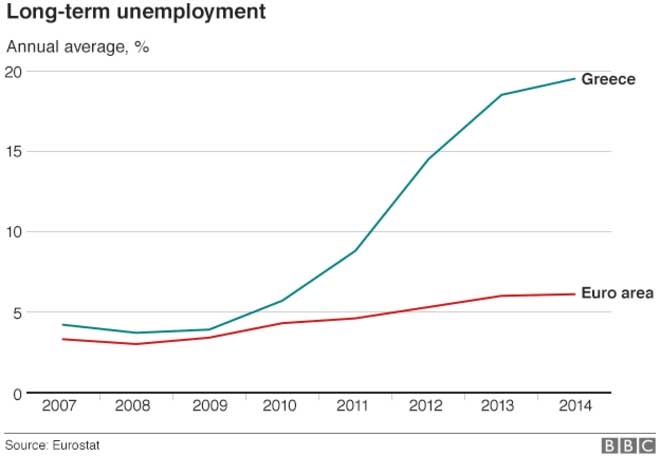

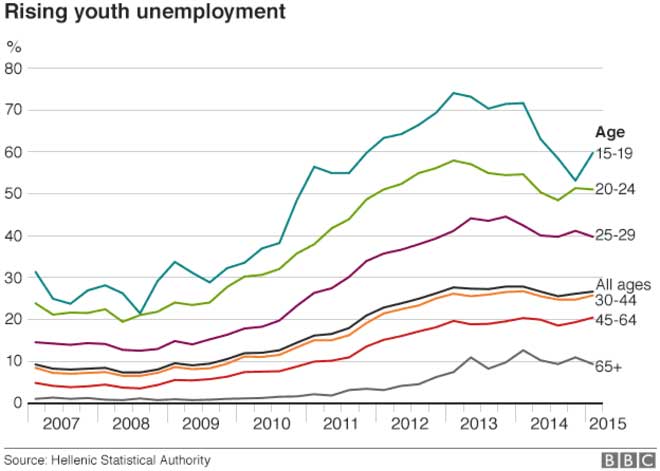

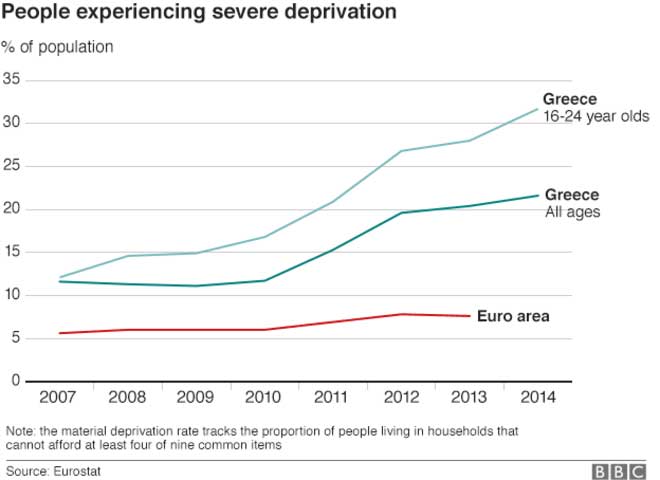

In the context of the Greek loan the ’unnecessary costs’ incurred by the Greek people resulting from the IMFs decision to ditch its own safeguards include:

IMF representatives have been upbeat about how positive the new policy is for the future performance of the IMF. The fact the Fund’s decision in 2010 to tear up its rule book has destroyed and ruined millions of lives in Greece is barely touched on.

“This latest reform to our lending framework is actually part of a broader reform agenda aimed at more efficiently resolving sovereign debt crises where they occur, as well as to prevent their occurrence in the first place,” said Sean Hagan, the IMF’s General Counsel.

“The reform is carefully designed to preserve the IMF’s ability to continue to provide financing to assist members in resolving their balance of payments problems, including in the presence of contagion risks,” said Hugh Bredenkamp, Deputy Director of the Strategy, Policy and Review Department of the IMF.

At the onset of the Greek crisis, many EU officials were insistent that the Eurozone take ownership of the issue. Analysts asserted that it was important for the Eurozone to demonstrate its strength and credibility by taking care of its own problems. The prospect of “outside” intervention from the IMF was viewed by many as a potential “humiliation” for the Eurozone, with officials at the ECB, among others, strongly opposed. In late March 2010, however, the debate in Europe appeared to shift, with the door slowly opening for possible IMF involvement as a number of member states came to favour a twin-track approach combining Eurozone and IMF financial assistance. In the end, IMF involvement was reportedly a key condition of German Chancellor Merkel’s willingness to provide financial assistance to Greece. The problem for the IMF, led at the time by the French socialist politician and French presidential hopeful Dominique Strauss-Kahn, was that without debt restructuring (i.e a write off of a significant part of the Greek debt) the proposed loans to Greece (the largest loan ever made in history) were clearly not sustainable. It was obvious that without debt relief the Greeks could never repay the giant loans being proposed and the proposed IMF contribution clearly breached its ‘quota’ guidelines for accessing financial viability.

When a country joins the IMF, it is assigned an initial ‘quota’ in the same range as the quotas of existing members of broadly comparable economic size and characteristics. IMF quotas are the financial commitment that IMF members make upon joining the Fund and are broadly based on the IMF member’s relative size in the world economy. The IMF uses a quota formula to help assess a member’s relative position when calculating how much it can prudently lend and how realistic loan repayments are. When an IMF member such as Greece requires financial support from the Fund the quota system results in an upper limit of what the IMF can lend to the country.

In “exceptional” situations, the IMF reserves the right to lend in excess of these limits, and has done so in the past. When a member is in need of financing that is far in excess of its quota, a certain set of criteria need to be satisfied before any fund resources are committed.

The four criteria for “exceptional access” are:

Greece had to meet all of those four criteria for the IMF to be part of the program. Given the nature and the volume of the problems that Greece faced back in 2010, the IMF could not asses the country’s debt as sustainable with high probability. Based on the framework that existed up to 2010 Greece would have definitely needed a debt restructuring and would need official financing on favourable terms so debt sustainability was not aggravated. The typical IMF package, based on its existing regulatory framework in place at the time would have required a substantial debt write down as part of the rescue package in order to make Greek recovery possible because the IMF did not assess Greece’s debt to be sustainable with high probability, and therefore the Fund’s own regulatory framework required an upfront debt reduction.

However, there were serious concerns at the time that this could lead to severe contagion both in the Eurozone and beyond. The contagion would have taken two forms. Government debt for eurozone members had harmonised at a low cost in the years between creation of the eurozone and the crisis of 2010. Financial institutions, mistakenly, believed that the debt of all eurozone members was collectively guaranteed which effectively meant the Germany was its guarantor, they thought the ECB was just the Bundersbank writ large. By 2010 the banks were waking up to the realities of the eurozone and as a result the cost of borrowing for the eurozone’s weaker member was beginning to soar threatening to make their debts unsustainable. If the Greek bonds took a haircut the market would begin to panic and government finances could collapse across the eurozone.

The second worry was that eurozone government bonds were a critical element of the financial ecosystem of the European banking system (see ‘Too big to bail – how the banks crashed the eurozone’). A Greek debt restructuring would imply that government bonds, which were considered risk free assets on banks’ balance sheets, would need to be risk adjusted and this would enforce additional capital requirements on banks that were barely recovering from the crisis of 2008-2009. If the value of these core assets were to be called into question, coming on top of the global and sub-prime financial crisis, many banks might fall into insolvency. This threat of insolvency was particularly acute for French and German banks with heavy exposure in the Greek government bond market.

So in order to save the European banks and prevent collapse of the flawed architecture of the eurozone the Greek people had to be sacrificed. Even though its internal functionaries urged a debt restructuring the management team of the Fund, led by Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the IMF did not insist on debt restructuring when it was called to Greece in the spring of 2010, instead it agreed to be part of a programme of 110 billion euros, with its contribution set at 30 billion euros. This translated into 3,200% of Greece’s quota and was the largest access of IMF quota resources ever granted to an IMF member country. The fact that Strauss-Kahn was intending to run for the French Presidency in 2012 and therefore did not want to be seen as being responsible for crashing French banks or the single currency project by insisting that the IMF stick to its rules almost certainly played a factor in the decision to overrule IMF staff concerns

The suffering caused to the Greek people by the insane logic of the eurozone, added and abetted by the IMF, can be shown in just three graphs.

Now the IMF admits that this policy is not working because:

Hindsight is not necessary to see that the Greek bailout was destined to fail from the start. An impossible task was compounded by the limited implementation capacity of the public sector and complex political and social dynamics. When the cracks in the program design were exposed as early as the beginning of 2011, Greece spun into a downward spiral of economic and social catastrophe of unprecedented proportions for a developed economy during peace time.

According to the reformed framework for exceptional access, Greece probably would have been given a debt reprofiling for all private claims in the three-year life of the programme, the IMF would have provided financing and the eurozone would have to give loans at favourable rates (unlike the 300 basis points over Euribor which Greece was charged in 2010 to ensure getting loans from one’s Eurozone partners would not be a particularly pleasant experience).

Greece’s debt was not addressed at the start when, by all admissions, it was necessary. Six years later it dominates the agenda, having climbed to just under 180 percent of GDP after three bailouts. The IMF has not confirmed its role in the latest programme partly because the issue of debt sustainability remains unresolved.

Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem recently suggested that one solution could be for the eurozone to promise that something will be done in 10 or 15 years, underlining the fact that there is little appetite within the single currency area for proper debt relief, just as was the case in 2010.

As if nothing has been learnt since then, Greece has to find an additional 3.5 percent of GDP in savings over the next three years to meet a primary surplus target that will give its debt an air of sustainability. The scale of fiscal interventions required is causing social tension, political instability, brings back country risk, halts investment, impacts on economic activity, hits the budget and so on and so forth. It is the same cycle that has been repeated over the last six years.

The IMF has been remarkably honest on the shortcomings associated with its involvement in Greece. This admission must now also be put in practice through a genuine change of course in the Greek programme.

Greece was denied the upfront debt restructuring that was needed and was forced into an austerity programme of such severe intensity and speed that it caused the economy to crash and impoverished the Greek nation. Since that fateful and flawed decision an intense austerity programme has continued to be imposed upon Greece meaning it cannot recover, it cannot grow, and its debt cannot be paid of. It is a pointless and perpetual circus of cruelty created by the insane logic of the eurozone but approved and supported at the time by the IMF.