When the UK leaves the EU, the Union will face a new kind of challenge: the departure of one of its largest and most important member states.

The Brexit negotiations will rapidly lead to changes regarding both the status of UK representatives and nationals in Brussels, the EU’s institutional arrangements, its policy agenda and the balance of power.

What would happen to the British contingent in Brussels?

UK representatives and nationals are currently present in all of the EU’s core institutions:

The UK’s Commissioner, Jonathan Hill, is responsible for financial stability, financial services and Capital Markets Union.

1,126 British nationals are employed in the European Commission (3.8% of the total).

73 British MEPs sit in the Parliament (out of 751 in total). Three EP committees have British chairs: Development; Internal Market and Consumer Protection; and Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs.

The UK is due to hold the EU’s rotating presidency from July to December 2017 and although there is no legal reason why the UK cannot hold the EU presidency in 2017, if still a member, it is probably politically untenable. Article 50 disqualifies the UK ‘from chairing any Council meetings on the withdrawal negotiations – meetings that would no doubt form a significant part of the Council’s activities’. A re-allocation of the presidency could cause some practical difficulties for the EU, given that a plan set for 2007– 20 ensures each member state holding the presidency once, for six months.

The British presence in EU institutions, defined as the number of UK nationals working at the Commission, has declined by 24% in seven years between 2006 and 2013 (no more up to date data is available). Relative to its share of the population (12.76%), the UK is underrepresented. Only 3.8% of Commission staff are UK nationals. In comparison, 10.2% and 12.5% are French and Italian nationals respectively. A large cohort of British nationals went to work for the EU in the 1970s when Britain joined, but subsequent generations have not followed their lead. Two EU agencies are, however, located in the UK: the European Medicines Agency and the European Banking Authority. Brexit would be disruptive for these agencies – at the very least they would need to be relocated. The Danish and Swedish pharmaceutical industry bodies are both keen for their countries to house the European Medicines Agency.

In terms of British officials in EU institutions, most commentators agree that mid-level officials on permanent contracts would probably be able to continue in their roles. However, according to Pierre Bacri, president of the European Civil Service Federation, director- generals and UK officials in top management positions would likely have to leave (which may explain why some British officials are looking into Belgian citizenship).

That might well apply to Commissioner Hill as well. Article 50 says nothing on the matter.

A reshuffling of European Parliament committee chairs will have to occur during the withdrawal negotiations. It will be impossible for for British MEPs to chair committees as relevant to the withdrawal negotiations as those on the Internal Market (trade and access) and Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (free movement). By contrast, aside from the loss of British judges, Brexit will not significantly affect the Court of Justice.

Brexit and the European Parliament

The European Parliament has 751 MEPS. It is unclear whether the UK’s 73 seats would be lost or reallocated.

Brexit would weaken the European Conservatives and Reformists: of their 75 MEPs, 21 are UK MEPs (mainly Conservatives), and Syed Kamall is the chairman. Brexit would also weaken the Eurosceptic Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy group, which Nigel Farage co-chairs. Of its 46 MEPs, 22 are from UKIP.

The Social Democrats would lose 20 of their 190 MEPs, but the left overall would be strengthened.

Brexit would alter the European Parliament’s party landscape and ideological composition. Nearly 60 percent of the UK’s 73 MEPs currently sit with centre-right and Eurosceptic groups. Their loss would strengthen the left, for the first time in years, the left would be able to form majorities without the European People’s Party. Brexit could, therefore, lead to a more social democratic Union. Whether the left and the social democrats have a reform agenda that they can deliver with their new majority is at this stage unclear.

A recent VoteWatch Europe report, analysing countries and MEPs’ voting behaviour in the Council and Parliament, suggests that Brexit could have the following policy implications:

EU’s foreign policy after Brexit

It is probable that Brexit will significantly weaken the EU’s global role. Britain is the EU’s foremost military power and also brings to the EU its significant diplomatic network, intelligence capabilities and soft power. Diplomacy, soft power and international cooperation are cornerstones of the EU’s foreign policy, which would be less influential on the world stage without the UK. For instance it is far less likely that the EU could have imposed sanctions on Russia without the UK (hence Putin’s support of Brexit). After Brexit, France would be the only major military power in the EU. Brexit could therefore undermine any future development of serious EU military capabilities – though progress has already been slow in this respect.

The EU balance of power after Brexit

Decision-making in the EU is complex, with EU’s main institutions, the Commission, the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament each having distinct roles. Of these, the Council – formerly called the Council of Ministers – is the body that is meant to represent national interests. In the Council, each member state is represented by an individual, but it operates with a complicated weighted voting method that ensures that larger countries have a bigger say in European matters. The Treaty of Lisbon introduced a system of qualified majority voting (QMV) which meant that unanimous decisions were longer mandatory in almost all areas of EU administration. This means that countries can be out voted and EU decisions approved by a qualified majority. The chart below shows the weight that the various EU member states had before Brexit, and that the UK had the third largest bloc of votes in the Council.

Under the Council’s current QMV system, both the Southern protectionist bloc (including France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal and Cyprus) and the Northern liberal bloc (including the UK, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland and the Baltics) hold a blocking minority. Without the UK, the collective weight of the liberal bloc would decline, whereas the protectionist bloc would strengthen.

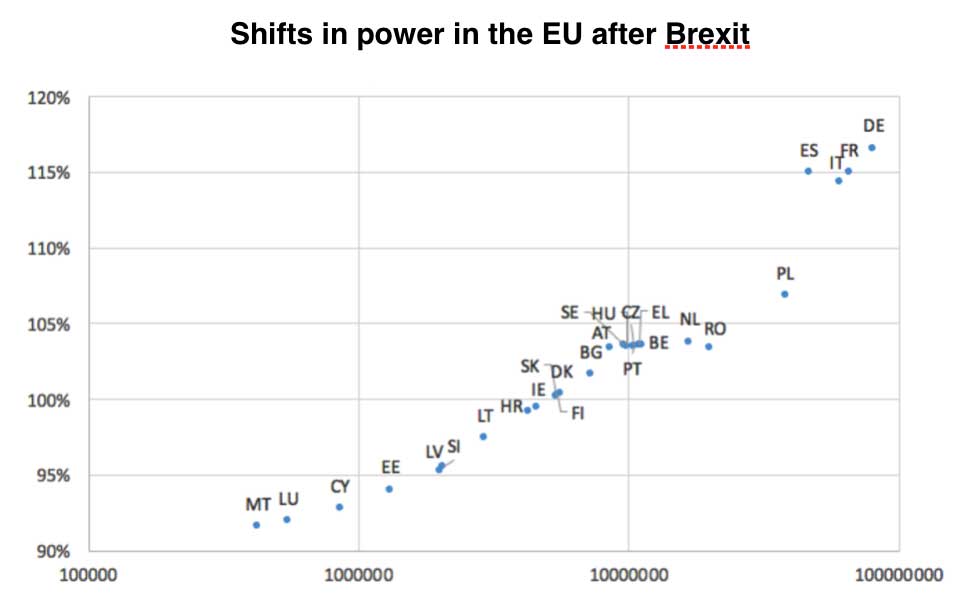

László Kóczy writing at the VoxEU.org, the Centre for Economic Policy Research’s policy portal, has calculated how the balance of power in the EU will shift following Brexit. The analysis used the latest available population data and population projections (Eurostat 2014) and software that can compute power indices of the main EU players). It is hardly surprising that after Brexit some of the remaining members would get a larger share of the ‘cake’, but some smaller countries are actually harmed. The UK is a net contributor, so the budget (the ‘cake’ at hand) is smaller, further harming these small member states. Interestingly, the gain of the larger members is larger than the loss of the budget. The chart below (taken from the Kóczy analysis) charts the way the power of all remaining EU member states will shift after Brexit, those below 100% will see their power decline and those above will see it increase.

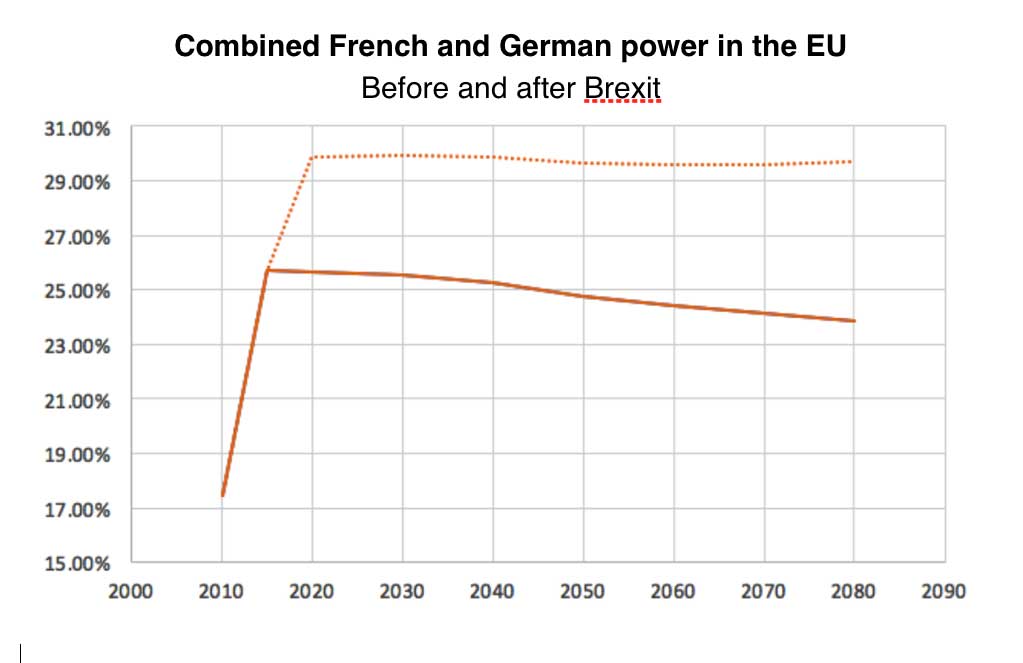

Based on these calculations it seems that the big core members of the EU would directly benefit from Brexit, at least in terms of power. France and Germany together used to have a combined power of 17.5%. This increased to 25.7% thanks to the Lisbon reform; after the Brexit this value would go up to nearly 30%, an increase of over 70% from the value a few years ago.

When Cameron was negotiating the package intended to win the referendum he was dealing with the big players who will actually benefit in terms of power from a Brexit. The fact that a Brexit would be beneficial to their national power standings, combined with a belief quite late in the game that the referendum would see an easy Remain win, meant that until the endgame the EU leadership didn’t take the threat of Brexit seriously. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the negotiations did not produce the results that could head off a Leave victory.

After Brexit, the EU will lose one of its largest and most important members. This will have a significant impact on the EU’s political system in the short and the long-term. Immediately after a vote to leave, Germany and France would probably push for deeper Eurozone integration, as a display of unity. Current EU initiatives with strong British support, such as TTIP and the Capital Markets Union, would be at risk. In the long-term, Germany could become more powerful – but so too could the protectionist bloc. Brexit could lead to a more left-leaning European Parliament and associated interventionist policies. It would also challenge the EU’s efforts to be a serious global actor. The big question – whether Brexit would pose an existential risk to the EU – may, not least, depend on the answers the Union finds to its current crises – stabilising the euro, finding a common line in refugee policy, stemming the surge in Euroscepticism – and on its economic recovery. A lot pivots on the political situation in France where opposition to the EU is much stronger than even the UK, and where the disparity between the position of the mainstream parties and the views of the electorate are now so great that a political crisis and a political earthquake could quite easily occur.