There seems to be a developing lobby amongst the institutions of the Troika to allow some sort of Greek debt relief. The IMF has come out strongly for debt relief, calling for “upfront” and “unconditional” debt relief for Greece and warning that without immediate action the financial plight of Greece would deteriorate dramatically over the coming decades. The IMF broke all its own rules and guidelines when it signed up to the original Greek bail out even though its own officials had warned strongly that Greece needed debt relief and that the Troika’s program would prove to be unsustainable (see “A strange dog’s breakfast” – the IMF, the Eurozone and the Greek crisis). Ever since that original blunder the IMF has been trying to detach itself from the unfolding disaster and is now digging its heels in and arguing publicly for debt relief.

Debt relief for Greece is still not a done deal, because of fierce resistance from Germany and its allies in the eurozone, and it might never happen, or be too little too late. The issue of debt relief for Greece will be discussed as if writing off Greek debts would be something special, some sort of special dispensation, and something that might set a dangerous precedent.

In fact there has been a massive program of debt relief that has been underway in the eurozone for a while now and every country in the eurozone has benefited – except for Greece.

To understand how and why this massive debt relief program has operated and why Greece has been excluded we have to rewind the clock back to the financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuring eurozone crisis that started in 2010.

Some background: the banks, government bonds and the crisis of the eurozone

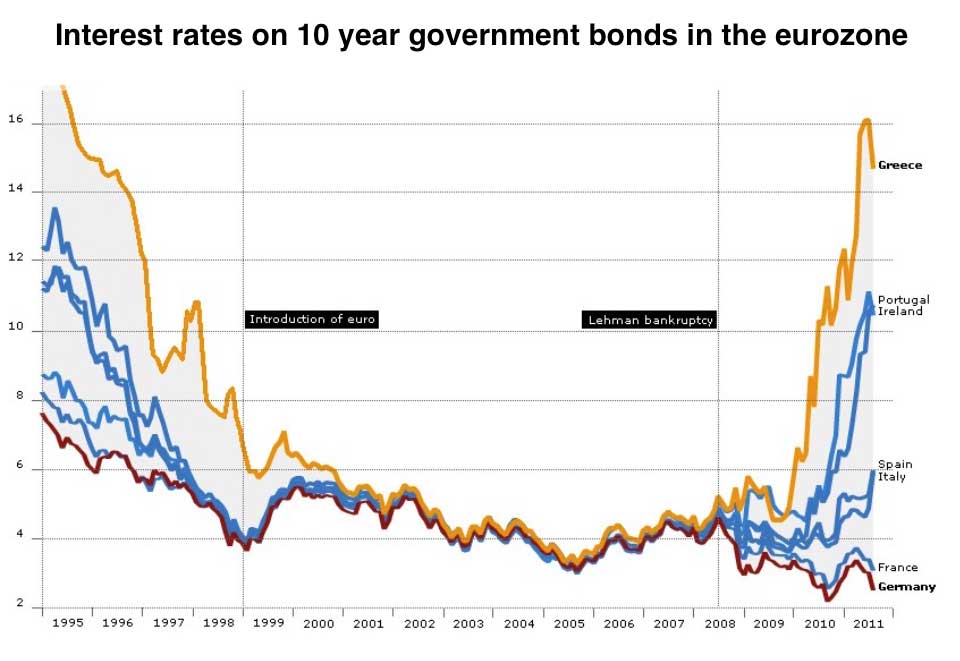

When the financial crisis hit in 2008 and developed into a generalised crisis of the eurozone in 2010 it revealed that there was a tight and very dangerous feedback loop between sovereign debt (i.e the bonds that all government sell to raise money) and the banking system in the eurozone (see this article). It turned out that the banks in the eurozone had been undertaking some truly dangerous and reckless lending, and they had been using eurozone bonds as the fuel and and essential lubricant for the manufacture of a mountain of debt being used to fund speculative asset inflation, mostly in the form of property development. When the asset bubble popped, first in the US, then the UK and then in the eurozone, the banks discovered that a lot of their assets were now more or less worthless. At the same time the interbank credit system, which used government bonds as a sort of core currency of credit exchange and guarantee, froze up. In this fraught crisis situation the revelation that the Greek government had been lying about is debts and was now suddenly declaring bankruptcy made the financial markets realise that they had made a terrible mistake in assuming that all government bonds in the eurozone were more or less equally safe and secure, that in fact the ECB (seen previously as the Bundesbank writ large) did not actually guarantee these bonds, and that the bonds of some eurozone countries were anything but safe and secure. To cap all these escalating uncertainities about soverign bonds in the eurozone the fiscal effect of the sudden crisis and subsequent recession wrecked fiscal planning across Europe, and many countries were in the throes of bailing out their collapsing banking systems at great cost, and this was causing a huge surge in public deficits and debt levels. The result was a rush to sell the bonds of the so called peripheral countries of the eurozone, such as Italy, Spain and Portugal.

Because government bonds, especially of the big developed countries, have for a very long time been considered to be a safe and secure investment there is a very big and developed market in the sale and trade of these bonds. Because it is so easy to sell government bonds they are considered very liquid, and because they are so liquid, and usually considered so safe, banks have alway held government bonds as an important part of their most secure reserves.

Like any market the price of bonds can go up and down depending on demand and this price movement is measured by reference to what is called the yield. When they are first issued government bonds are sold for a fixed price, which is their face value, and with a fixed redeem date (when the bonds face value will be repaid), and with a fixed rate of interest that is paid regularly over the years based on the original face value of the bond. So for example if a government bond is sold with a face value of 100 euro for five years at 2% interest it will pay 2 euro every year for five years at which point the original 100 euro is paid to the owner of the bond. During its life the annual 2 euro interest is paid no matter how much the price of the bond rises or falls as it is traded in the markets. If the price of the bond goes up, because there is so much demand for it, and the price rises above the face value of the bond then the rate of interest, the yield, will fall because although its market price has increased its still only paying 2% of the original 100 euro face value. So if there is strong demand for a particular bond, lets say German five year bonds, then their traded price will go up and the yield in the markets will fall. Continuing with our example of German bonds, a fall in German yields (because there is high demand for German bonds) will have a big impact on the ongoing finance of the German state because the German government is always selling new bonds as it rolls over and refinances its existing government debt and the interest it has to pay in order to attract buyers for its new bonds is effectively set by the yield rates in the bond markets.

Its easy to see then that the yields on government bonds are a crucial determinant of how expensive maintaining (refinancing) government debt is. If demand for a particular government’s bonds falls because the markets are worried about the state of that countries government, debt or general economy, then the price of its bonds will fall, yields will rise and as a result it will have to pay higher interest on any new bonds it sells in order to attract buyers. So rising yields make it a lot more expensive to refinance and maintain a government debt. It doesn’t take more than a rise of a few percentage points to turn a sustainable government debt into an unsustainable and spiralling debt. A sharp move in market sentiments, which can happen very quickly, can capsize government finances very quickly.

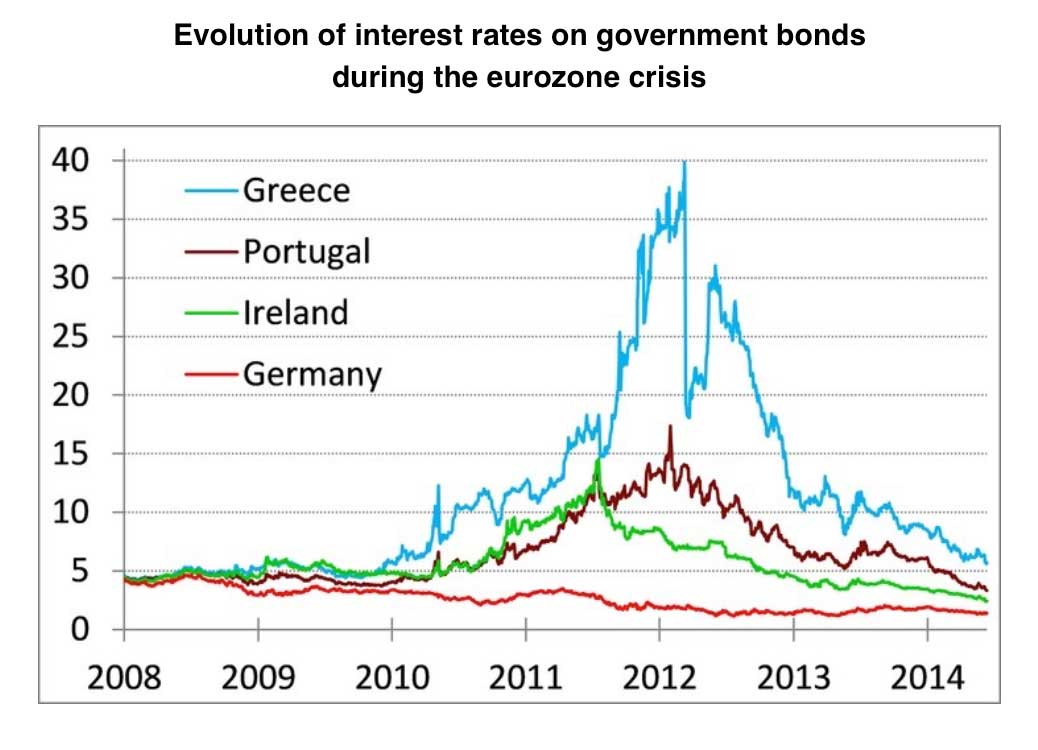

And that is exactly what happened in the eurozone crisis of 2010. When in the midst of an already serious financial crisis the banks were confronted by the revelation that not only was Greece bankrupt, but there was also no automatic mechanism in place for the the European Central Bank (ECB) to underwrite or guarantee Greek government debt the markets took fright. Not only was the ECB not, apparently, committed to supporting eurozone bonds, but the existence of the eurozone system meant that national central banks were now just branch offices of the ECB and they could no longer underwrite national finances. In a very short space of time yields on Greek, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish and Italian bonds began to sky rocket, and this meant that those national government were now paying unsustainably high interest rate rates in order to sell new bonds and service/refinance their national debts. And because eurozone bonds were being held as apparently super safe assets by eurozone banks, and being used as collateral in a vast number of interbank loans, the crisis threatened to capsize the already fragile balance sheets of numerous eurozone banks. It was a perfect storm.

As first the ECB and the eurozone governments seemed to be confused and immobilised by the crisis but eventually, slowly, they began to respond. Greece was not allowed to go bankrupt and was prevented from defaulting and thus writing off its debts, instead it was be lent a vast amount of money and the economic management of the country was be taken over and dictated by the Troika (the EU, the IMF and the ECB) who forced through an absurd and cruel program of relentless austerity that all but collapsed the Greek economy and impoverished millions of its citizens. Meanwhile under a new president, Mario Draghi, the ECB became proactive in talking down the fears of the markets and helping bond yields to fall.

Quantitative Easing

The US (beginning in 2008) and the UK (in 2009) had responded to the financial crisis with a new and innovative monetary mechanism known as Quantitative Easing (which is explained below) and eventually, and very late in the game, the ECB began its own programme of Quantitative Easing (QE) in 2015. As explained below it is this program of ECB program of QE that constitutes a form of massive debt relief for eurozone governments – all of course except for poor old Greece.

Quantitative Easing (QE) is a new an innovative form of monetary intervention by central banks. Because when the 2008 crisis struck one of its manifestations was a surge in public debt, and because the preceding decades had seen an idealogical shift away from using public spending to balance cycle shifts in the economy, there was a reluctance to respond to the post crisis recession using fiscal policy. This reluctance was not universal. The US did pass a fiscal stimulus program (strongly opposed by the Republicans) as part of the first phase of the new Obama administration, and for all its talk about the need for austerity the UK has oscillated between tightening and loosening of spending. However in the eurozone because there was a pre-existing commitment, enshrined in the rules of the eurosystem, to holding deficits down there has been a deep resistance to using public spending to boost output. Not surprisingly this has led to a prolonged stagnation and high unemployment in Europe.

The new policy of QE was seen as offering a non-fiscal monetary policy response to the crisis and the recession. The mechanism of QE is fairly simple: central banks create new money by typing a figure into their electronic ledgers. The central banks then use this newly created money to buy in the markets various types of bonds and financial assets, mostly they buy government bonds. It is hoped (and nobody is entirely sure exactly what the real world effect of QE will be) that this buying of assets will have a number of beneficial effects. It will turn assets held by banks into cash and this it is hoped will encourage the banks to lend more money, so QE is seen as a way of injecting money into the economy (via banks). In addition if a central bank is very active in the markets buying government bonds it will help push up the price of those bonds and thus push down yields and as we saw above this will make it much easier for governments to manage their deficit and debts.

This Bank of England video explains how QE works.

The idea is that at a later date, when the economy, government financing and credit system have all strengthened the central banks will eventaully be able to sell the bonds thay have bought and unwind the QE program. But there is no mechanism in place to force the central banks to do this and they could hold on to these bonds pretty much for ever, or at least until their redeem date.

QE as eurozone debt relief: but not for Greece

Although it was late in adopting the new policy of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE), the ECB has been buying government bonds of the Eurozone countries since March 2015. Since the start of this new policy, the ECB has bought about €645 billion in government bonds. And it has announced that it will continue to do so, at an accelerated monthly rate, until at least March 2017. By then, it will have bought an estimated €1,500 billion of government bonds. The ECB’s intention is to pump money in the economy. In so doing, it hopes to lift the Eurozone economy out of stagnation. The ECB buys government bonds from every country in the eurozone, except for Greece. Because Greece is in a special program of supervised intervention and bail out, it is specifically prevented from participation in the ECB QE programme. As a result, the ECB excludes Greece from the debt relief that it grants to the other countries of the Eurozone.

When the ECB buys government bonds from a Eurozone country, it is as if these bonds cease to exist. Although the bonds remain on the balance sheet of the ECB (in fact, most of these are recorded on the balance sheets of the national central banks), they have no economic significance anymore. Each national treasury will pay interest on these bonds, but the central banks will refund these interest payments at the end of the year to the same national treasuries. This means that as long as the government bonds remain on the balance sheets of the national central banks, the national governments do not pay interest anymore on the part of its debt held on the books of the central bank. All these governments enjoy debt relief.

How large is the debt relief enjoyed by the governments of the Eurozone? The table below gives the answer (source). It shows the cumulative purchases of government bonds by the ECB since March 2015 until the end of April 2016. As long as these bonds are held on the balance sheets of the ECB or the national central banks, governments do not have to pay interest on these bonds. The ECB has announced that when these bonds come to maturity, it will buy an equivalent amount of bonds in the secondary market. As can be seen the total debt relief granted by the ECB until now (April 2016) to the Eurozone countries amounts to €645 billion. Note the absence of Greece and the fact that the greatest adversary of debt relief for Greece, Germany, enjoys the largest debt relief from the ECB.

| Cumulative purchases of government bonds by the ECB to the end of April 2016 (million euros) |

|

|---|---|

| Austria | 18,761 |

| Belgium | 23,634 |

| Cyprus | 269 |

| Germany | 171,808 |

| Estonia | 66 |

| Spain | 84,478 |

| Finland | 12,025 |

| France | 136,510 |

| Ireland | 11,054 |

| Italy | 117,795 |

| Lithuania | 1,554 |

| Luxembourg | 1,573 |

| Latvia | 875 |

| Malta | 483 |

| The Netherlands | 38,229 |

| Portugal | 16,513 |

| Slovenia | 3,233 |

| Slovakia | 6,513 |

| Total | 645,102 |

The announcement of the ECB that it will continue its QE programme until at least March 2017 and that it will accelerate its monthly purchases (from €60 billion to €80 billion a month) implies that the debt relief that will have been granted in March 2017 will have more than doubled compared to the figures in the table above. For many countries, this will amount to debt relief of more than 10% of GDP.

Greece is excluded from the QE programme, and thus from the debt relief that arises as a result of this programme. The ECB gives a technical reason for this exclusion: Greek government bonds do not meet the quality criteria required by the ECB in the framework of its QE programme. But that is extremely paradoxical. Countries that have issued ‘quality’ bonds enjoy debt relief. As soon as they are on the central banks’ balance sheets, these bonds cease to exist from an economic point of view. It is as if they are thrown in the dustbin. Thus this whole operation amounts to throwing the good bonds in the dustbin, but not the bad bonds.

The exclusion of Greece is not the result of some unsurmountable technical problem. These technical problems can easily be overcome when the political will exists to do so. The exclusion of Greece is the result of a political decision that aims at punishing a country that has misbehaved. In the topsy turvy world of the eurozone the country most desperate for debt relief, the country that has suffered a massive collapse of its economy caused by trying to repay its debt, is the one country that is not given debt relief. And the country least in need of debt relief, Germany, gets the most debt relief.

Fascinating if depressing article! There seems no way out for Greece!

I note this morning that the IMF caved in the eurogroup meeting and did not get outright agreemnent to immediate debt relief, instead agreed to ‘potentially’ offer Greece debt relief. Same old crap.

BTW I wrote the article in a bit of a hurry and this morning noticed and corrected quite a few typos, not least when using Germany as an example to explain yields I left in references to Italian bonds (my first choice of example country) which made that section a bit confusing. All fixed now I hope.

Comments on this entry are closed.