‘God Save the King!”

Sounds odd doesn’t it? Jarring almost, perhaps a bit anachronistic?

Such is change. Why does it matter? It probably matters to those who consider themselves republicans and who would like to get rid of the monarchy. I am sure for republicans the explosion of ceremony and pomp around the Queen’s death and the accession of Charles III is pretty hard to stomach. Probably a fair bit of groaning, possibly some sneering, maybe even some despair. I suspect that republicans are over represented on the left wing and this article is an attempt to explore the issues of the monarchy in relation to the political project of progressives and the left wing of politics (I’m just going to call it the ‘Left’ from now on). I am worried that the Left is making political blunders, and these blunders speak to quite deep weaknesses in how the Left thinks about it’s own political project.

I haven’t thought that much about the monarchy over the years. I used to be a republican but I’m not anymore. I feel relaxed to live in a constitutional monarchy. All in all it seems an OK way to arrange things constitutionally. The democratic countries that have non-monarch heads of state have not done any better than the UK and some have done a lot worse, and several of the most stable countries in Europe, with admirable records on human rights and social care, are constitutional monarchies. So it’s not as if there is a clear cut argument that getting rid of the monarchy and replacing it with a political head of state (elected or appointed) would automatically make things better. And the cost of getting rid of the monarchy, unless the crown disgraced itself by siding with an attempt to overthrow democracy or with a foreign invader, would almost certainly be pretty high, possibly catastrophic. Imagine a situation where a referendum is won by the republicans but as is likely a very sizeable minority want to keep the Crown. For monarchists the Crown is the nation and attempts to overthrow the Crown are treason. Such feelings almost certainly run very deep in the state apparatus, especially in the armed forces. Sacking the King, seizing the Crown estates and installing a new political president would tear the country apart, and lead too deep, possibly very violent, conflict. And for what? What great progressive project could be taken forward under a political head of state that cannot be taken forward under a King?

I think that there are a higher proportion republicans on the Left, especially on the radical Left, than there are in the country at large, because being republican is now part of the repertoire of positions that for quite a lot of people define what being leftwing means. When the western Left was reconstituted, after global capital restructured and relocated the industrial working class in the last quarter of the 20th Century, it became predominantly a graduate movement. At the same time the collapse of actually existing socialism created an ideological void as historical materialist ideology retreated. This void was filled by variants of post modernism, green ideology and identity politics, so the nature of being Left has changed. Nowadays being Left mostly means supporting various, and often unrelated, tent pole positions that are used to mark people’s identity as belonging to the Left tribe. Being against the monarchy is one such position.

In a lot of modern Left political discourse political positions are used as identifiers of virtue (‘I believe/say/support/campaign for the right things’ therefore I am good) rather than as the result of actual real strategic political calculation (i.e calculation about a practical way to make specific political developments happen). Supporting the accepted cluster of positions that are used to define the Left is what makes people feel they are part of the Left. And if you are part of the Left tribe you are sort of expected to be be a republican and against the monarchy. The practicalities of abolition, or what might replace the monarchy, or whether it is even good idea, are rarely discussed.

In the past, before the great structuring after the 1970s, all sorts of what might be called secondary positions could come and go as part of the repertoire of Left orthodoxy at any one time but the Left was always organised around a constant central hub, which was a commitment to socialism, and was linked deeply and organically with the organised industrial working class. Back then what socialism actually was, was also pretty clear. It was the abolition of the private ownership of the means of production and the reorganisation of the economy as a democratically managed planned social undertaking designed to maximise the well being of the population. So back then the fundamentals of doing Leftwing political calculation was relatively straightforward: that which advanced the journey to socialism was good, that which moved things away from socialism was bad.

Since the collapse of actually existing socialism, an experiment that ran for many decades and at its peak organised the lives of about a third of the earth’s population, explicitly campaigning for the introduction of socialism as a practical and achievable system has almost no political traction, even on the Left. Leftists talk a lot about socialism amongst themselves but I have never seen any example of a plan for how a socialist system of production might work – a real, practical and detailed plan – that is in any way different than the sorts of planned economies that used to exist under communism. The radical Left remains committed to getting rid of capitalism but there are no specific plans for what might replace it. Socialism is no longer presented unproblematically as being a planned rational economic system, replacing the ‘chaos’ of capitalism, because even three decades after the collapse of the actually existing socialist planned economies nobody has come up with alternative alternative for capitalism. Only an idiot or someone ignorant of their real nature would suggest that the old planned economies are worth recreating. People used to risk their lives to escape the planned economies, they had to be locked inside them, and eventually they rose up and overthrow them. That’s a clue that it was a pretty shitty system.

The trouble now is that a lot of Leftist discourse consists of a kind of ethereal and nebulous commitment to something called socialism which remains essentially undetermined but which will be, we are told, wonderful. Here socialism becomes like a political concept developed by Heisenberg, it only works if you don’t look at it too closely. Alongside this elusive thing called socialism there is, handily, a lot of hard and firm commitments to a whole cluster of more or less unconnected political positions (‘Black Lives Matter’, ‘Net Zero Now’, ‘Transwomen are women’, ’No immigration controls’, etc, etc). These come and go, rise and fall in importance, with the ebb and flow of political fashion, often driven by the dynamics of social media connections.

Back before the post-1970s deindustrialisation the working class, replete with its own civil society rooted in organised labour and cohesive working communities, had real political, social and cultural weight. That weight formed the ballast of the Left, but now in our post industrial society, with the old components of the working class eroded or gone, the modern metropolitan graduate Left, bereft of an organic connection to a well organised industrial working class, lacks an idealogical anchor.

What used to be its idealogical anchor, the belief in a tangible, concrete and achievable goal of creating a socialist planned economy, is no longer tangible, concrete or achievable. Even though in principal most people of the Left, particular the radical Left, would profess to a belief in socialism in reality nobody on the Left now knows what socialism is. Apparently it’s not going to be like those unpleasant planned economies in the old communist regimes, it’s going to be better, but the details are all missing. If anything socialism nows means an aggregate of the single issues that concern the Left and a vague idea that these can all be stitched together into something just, and fair that will, somehow, replace capitalism with something much better. In reality campaigning for this vague concept of socialism is not really what makes up the real day to day content of leftwing politics, instead the Left clusters around a shifting series of ‘positions’. Over time these can come and go (who ten years ago would have thought that the issue of whether a woman could have a penis would be a big political issue?), and when an issue suddenly gets hot (transgenderism, BLM, Net Zero) enormous amounts of political energy can be expended around it. The problem is that lacking a real core strategic aim (if one accepts that building socialism is no longer viable as the core) the focus and attention of the Left can wanders about and it often seems to end up being a long way from what I would call progressive politics (what I think progressive politics actually is I will get to very shortly).

Now with the flurry of intense ceremonials and saturation media coverage of the royals I fear some of the Left will rediscover a new enthusiasm for republicanism. As I explain below that would be a political mistake. But the issue of the propensity on the Left to align with republicanism is also important because it is connected to some really profound errors on the Left, most of which are connected to its relationship with the nation and a deep strategic confusion about what its job actually is.

So what’s wrong with the Left having a go at the Crown? In principle nothing but under current conditions It plays to some deep, deep weaknesses in Left politics, weaknesses that underpin a lot of its political failures. In order to understand the weakness of the Left, on both the issue of the Crown and on the the much broader and connected issues of patriotism and the nation, we must restate what the Left is actually for, what’s its political job is, before talking about how that relates to the nation and the Crown. I would argue that the job of the left, in a post socialist world, is both clear and important. The Left’s job is to do two things, which are:

Work to improve the material welfare of the people

Work to increase social solidarity

I am not going going to focus on the first task for the Left, improving the material welfare of the people, other than to say that material welfare should be interpreted in the broadest sense, as working to bring about those conditions which are required for everyone to lead a good life.

I do want to focus on the second issue – which is increasing social solidarity – because it’s here that the questions of the monarchy, the nation and patriotism sits and its here where the Left makes so many costly mistakes.

By social solidarity I mean not only that which is required so that all citizens feel included and welcome but also – and this is very important – the real material social solidarity that underpins the massive transfers of income which take place routinely inside modern developed states, transfers from the richer to poorer, from rich citizens and rich regions to poor citizens and poor regions. This material social solidarity encompasses all spending on such things as social welfare, pensions, and social health care, etc. Although the Left needs to work to increase all forms of solidarity, including non-material solidarity, it must remain primarily focussed on how to improve and deepen material solidarity, because people can’t eat words, and not allowing our fellow citizens to fall into poverty must be the central pillar of social solidarity.

Currently it is hard for a lot of people on the Left to do effective political calculation because if socialism is missing as an option it leaves a lot of ‘socialists’ confused about what their primary political function is. If the Left could collectivity drop the mirage of a non-existent, non-possible and frankly non-desirable socialism as it’s central principle and instead sharpen its focus on the fundamental issue of social solidarity, and try to avoid being constantly distracted by secondary and perhaps unrelated issues, it would make political calculation easier and more effective. It could contribute to a greater clarity about how to position itself politically around around the complex and controversial questions of the day. The first thing should always be to ask “will this policy/slogan/campaign/position strengthen or weaken social solidarity?” The direction of travel should always be towards that which strengthens social solidarity and away from that which weakens it. It sounds obvious but much of the Left often loses sight of this fundamental strategic positioning, and incapable of seeing the wood for the trees, either wanders off into a self inflicted isolation or even worse finds itself promoting divisive political positions that actually undermine social solidarity.

“To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

George Orwell

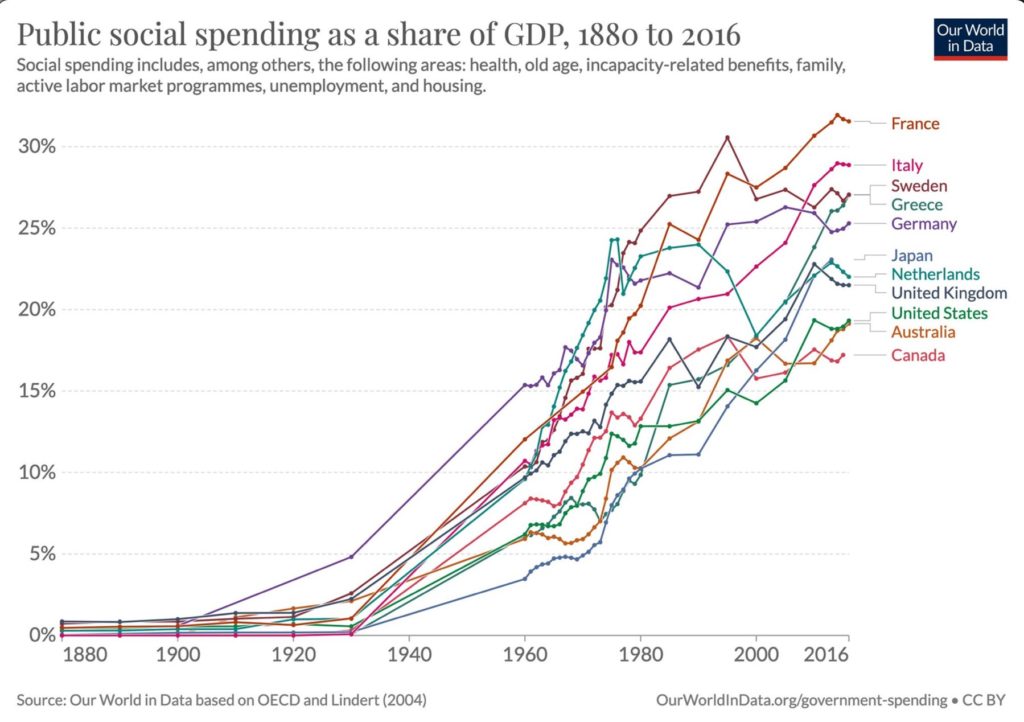

It’s time to talk about nation states and their relationship to the politics of the Left. The chart below shows the trajectory of social spending as a percentage of GDP from 1880 to recently. Social spending is the concrete expression of social solidarity, generally the more that is spent the greater the degree of solidarity. In any given society its possible that solidarity is not evenly distributed amongst its beneficiaries so the absolute level of spending will miss some of those fine grained difference, but nevertheless if spending is higher it mostly means more solidarity and if its lower then it usually means lower solidarity.

A few things stand out from this graph. The upward rise in social spending started before WWII, and although it varies from country to country it has continued to grow steadily. Somewhere in there are the Thatcher years in Britain and the supposed generalised triumph of Neoliberalism in the last few decades – but you would be hard pressed to see that from the general trend in the data. Social spending has grown and grown. Social spending, the material expression of social solidarity, now makes up somewhere between 17%and 30% of national GDPs depending on the country. That’s a lot of solidarity.

But here’s the thing that is right in front of our noses. All that spending is strictly inside nation states. Cross border transfers of tax revenues from one country to fund social spending in other countries anywhere in the world is almost non-existent or at best minute. Even in the EU, a serious and protracted multi-decadal project to build a cohesive transnational community, there are almost no cross border transfers to fund social solidarity.

So what does that tell us? What’s in front of our noses? It is this – all successful and substantive projects of social solidarity are built on the top of national communities. Social solidarity stands on the base of the solidarity of the national community or it doesn’t stand at all. This is a very important idea, one that should be central to all progressive political strategy.

Now that fact – that social solidarity only works if it’s built on top of cohesive national communities – is a hard pill for lots of Leftists to swallow. Generally Leftists like to aspire to internationalism and often yearn to move beyond what they see as the petty, and sometimes deeply suspect, patriotism of the nation. The mental categories that Leftists tend to think in (working class and capital, imperialist and colonised, oppressor and oppressed, black and white people, etc) all tend to look at things in ways that make national borders blurry, indistinct and unimportant. The first instinct of a Leftist is often to criticise rather than celebrate their own national community. That’s a dangerous instinct as it can in practice lead to a weakening national cohesion and hence the erosion of the national foundations for projects of social solidarity. Also being automatically associated with what to most other citizens seems like opposition to the nation itself isn’t exactly the path to mass popularity. Leftists often seem oddly reluctant to praise their own nation, almost embarrassed by celebrations of their own country, its history, its symbols, its achievements. As soon as something good is said about our nation the first response from the Left is ‘yes but…..”, followed by something negative about the nation or its past.

Because the metropolitan and cosmopolitan Left, rooted in the graduate class and not the manual working class, is over represented in the universities, the media, the cultural industries, the NGOs and other bodies of civil society, its inherent tendency to latch onto and promote anything critical about the nation whilst ridiculing or attacking anything celebratory, carries some weight in society and it can easily contribute to a shredding or weakening of the cohesion of the nation. But as we have seen all social solidarity is built on the foundations of the nation so a weak or fractured sense of national community means a weak base for projects of social solidarity.

“England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality. In left-wing circles it is always felt that there is something slightly disgraceful in being an Englishman and that it is a duty to snigger at every English institution, from horse racing to suet puddings. It is a strange fact, but it is unquestionably true that almost any English intellectual would feel more ashamed of standing to attention during ‘God save the King’ than of stealing from a poor box.”

George Orwell

For some reason this deep distrust of patriotism, and this deep disenchantment with their own nation, runs particularly deep in the British Left. All nations (indeed all nations, empires, ethnic groups, tribes, or any other such organised grouping of peoples) has bad stuff in its past, and sometimes they have good stuff. Britain has some bad stuff in its history, but which other national history is a whole lot better? We also have some amazingly good stuff in our history, stuff we can be justifiably be proud of. The things that Leftists most like to talk about when they talk about British history are the Empire, colonialism and slavery. Leftists quite often accuse their opponents, and our national institutions and culture, of being obsessed with our imperial past but it’s actually the Left that cannot stop talking about the Empire. Most of the time when they talk about Britain today they sound like they are talking about an imaginary country and not the the least racist country in Europe (by a very long way) and the country that now has politicians of colour holding three of the top four offices of state (and the other one – their boss – is a woman). Not bad for a racist patriarchy.

If all communities of social solidarity are built on national communities then it stands to reason that the really basic job of the Left is to articulate and shape the discourse of national identity into a discourse of ever deeper social solidarity. That means creatively embracing most of the institutions, rituals, symbols and components of our British national identity and constructively remoulding them in to a new sort of national community of ever deeper social solidarity. What it shouldn’t mean is just picking away at the things that make up the fabric of the national identity whilst not putting anything in its place to strengthen our national cohesion. All that does is weaken national cohesion whilst failing to create the conditions for greater social solidarity because such solidarity has to be built upon the firm foundations of a coherent national community. Why should well paid people in London care about poor communities in the rest of the country, or the poor in their own city for that matter, if there is nothing that binds all those communities together into one thing?

The British national identity is really interesting and has some built in features which means that there is a lot of raw material which can be used as a basis for projects of social solidarity. Britain as a nation state was only invented just over 200 years ago with the final union of Scotland, England and Wales. Originally built structurally around a pre-existing shared monarchic dynasty, and a shared commitment to variants of Protestantism, the union actually worked very well and a new shared and mostly popular identity as Britains was created very quickly. Things were much more problematic in Ireland where the prevalence of Catholicism made participation in the British union very problematic. By the time the protestant ingredient of Britishness began to fade in importance it was too late, and the Irish were on their own and separate national trajectory.

There are many aspects of this new British identity that are interesting but for the purposes of this article I want to focus on one aspect: the role of the Crown in relation too belonging and inclusion. Nation states can be built from many components and in many ways, all that matters is that various social process and features (geography, religion, language, conflict with neighbours, etc) causes a powerful imaginary community to be brought into existence and then sustained via various institutions and customs. In the case of Britain a very powerful component of the new nation called into existence with the union of Scotland and England, was the monarchy itself. Prior to Union the Scottish and English crowns had been unified in one monarch and one dynasty. Then this single crown was tamed by the wars, revolutions and upheavals in the 17th century so that by the time of Union it was a well organised constitutional monarchy, no threat to the supremacy of parliament, but replete with a rich set of ceremonies, symbols and pageant (many of which had been created quite recently but then given an invented deep history) so that the single iridescent overarching, but politically neutral, monarch could become a strong part of what glued the union together. Fundamentally what made someone British was loyalty to the Crown, and all the Crown’s subject were notionally equal before the law as subjects of the Crown and as a result each possessed the same set of basic human rights. Of course in reality people were far from equal and this system allowed immense inequality, exploitation and oppression (then there is the question of slavery – more on that below) but nevertheless the system also delivered some uniquely progressive things such as among other things an essentially free press and no censorship – in the 18th century!!

The point of all this is that for all the reality of oppression and exploitation at the time, this idea of a single national identity which binds together an ethnically diverse collection of people’s from its constituent nations with equal civil rights and, and a shared set of mutual obligations and rights, as subjects under one non-political Crown is an interesting one with a lot of potential. In our modern times the role of the British identity, as separate to the identity of being specifically English or Scottish, has been invaluable in allowing new ethnic groups to find a place of belonging in Britain. It was relatively easy for example to talk quite early on and relatively unproblematically about ‘British Asians’ in a way that many other nations in Europe would struggle to match. Similarly it’s easy to use the phrase ‘British Muslims’ because the British identity is so fluid, just loyalty to the Crown. In fact the ‘Lite’ version of Britishness which said just be loyal to the crown and pay your taxes and your welcome to be part of our country actually has proved a bit problematic. It turned out that this version of multiculturalism was too weak, and we need to add on to the formulae for being British other things that people need to accept of adopt, and the debate about what should or should mot be included in the notion of what is British is tricky and ongoing. The point is that the Left needs to take part, and it needs to recognise that the existence of an overarching non- political, but ceremony and pageant rich, Crown is actually a feature and not a bug. This essentially neutral monarchial superstructure opens up a whole space for progressive politics built on a progressive notion of nation (‘we really are all in this together’) and a place to develop progressive strategy and a national community of progress (‘Is it really British to have so beggars on the street, and food banks?’).

I hope you can see where I am going with this. Institutions like the Crown, and indeed national identity itself, are malleable and both the Right and the Left can reshape them to their own ends. The problem is if the Left decides not take part, perhaps instead to opt for a ‘principled’ anti-monarchy republicanism, a strategy probably doomed to failure and even if successful fraught with danger, then it is the Right that can bend the notion of the Crown too it’s own ends. In practice this would mean the Right promoting a notion of Britain as made up of a sort of loose collection of self reliant, self seeking, individual subjects of the Crown free to take advantages of opportunities but also free to pay the costs of failure or lack of effort. In short a concept of the nation that tends towards weaker social solidarity. A bit more like the USA in fact.

When people say “God Save the King” they are not saying anything about God, an atheist can say it, and they are not actually saying anything about the King as a person or institution. What they are saying is ‘I’m British along with everyone else who says ‘God Save the King’, we are all together, we are part of our one national community, this is our country, our Britain, it belongs to us all, and we belong to it.” Those sentiments have a great potential for helping to build a national community of social solidarity.

“Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past,”

George Orwell

Slavery as an example of doing progressive national history.

The past is not really about the past, it’s about the present. Part of the creation of nation states involves the creation of a shared, and often imaginary, deep history of the nation stretching back into the past. Modern histography was mostly invented quite recently as part of the emergence of modern nation states in order to develop specifically national histories. As the sacred time of Christendom faded away the sacred eternity of God was replaced by the eternity of the nation. Modern nation states, and the members of national communities, came to share a secular common past (Benedict Anderson, in his now classic Imagined Communities, argues that the nation lives in ‘homogeneous empty time’) that stretched back into prehistory and a common trajectory into an eternal national future. I will die, all whom I love will die, but “There’ll Always Be an England”.

So if you accept my argument about the centrality of the nation to the Left’s project of building deeper social solidarity how should the Left interact with those parts of our nation’s history that are bad or difficult? I would suggest two important rules of thumb for how the Left should do national history. One is don’t replace a mythical national history of perfection and greatness with another mythical history of malevolence and wickedness. And secondly if the Left wants to criticise and take down something to do with Britain’s history then at the same time it needs to replace it with something from Britain’s history that brings the Britain of today back together with a new refurbished sense of national pride and cohesion.

An example of how a progressive national history should be constructed is the topic of slavery. One way to do this topic, the way currently favoured by a lot of the Left, is to say that in the recent past something called “Britain” ran a giant hideous slave empire, that this Britain got rich on the back of slavery. That modern Britain is tainted by this terrible thing. That white people in Britain should feel a sense of guilt about slavery, and that black Britains should feel a sense of victimhood about slavery. That this history of slavery lives on as modern day racism in Britain.That we should tear down any aspect of our current British heritage (place names, statues, etc) that can be even remotely connected to slavery and teach our children to feel ashamed about our country’s history of slavery. Full stop.

There are a lot of problems with this approach, not least that it’s hard to see how in reality it strengthens our sense of national cohesion, but also because it is an example of doing a new mythical history (Britain used to be evil) in order to replace another mythical history (Britain used to be perfect).

Here are several facts about Britain and slavery that are all true, and which can be assembled into a different progressive national narrative.

All previous societies, nations, empires and tribes in all of history practiced slavery. Slavery was always, until quite recently, a universal and unexceptional part of all human societies.

Historically slavery was not a racial phenomena. It was partially ethnic in the sense that it was often subjugated or enemy ethnicities that tended to be enslaved, but slavery within ethnic groups was very common.

Then starting at the end of the 18th century one particular nation, which also happened to be very powerful and growing in power, decided to oppose slavery, first banning the trade and then banning the holding of slaves in any territory it controlled. That nation was Britain. No other nation, and certainly not one that was powerful enough to do more or less what it wanted, had taken so definitively and permanently against slavery like this before. Moreover Britain then created a new and specialist division of the Royal Navy, the West Africa Squadron, whose sole and full time job it was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade through the use of force if necessary. The West Africa Squadron intercepted hundreds of slave ships and freed about a hundred and fifty thousand slaves, in the process hundreds of British sailors died fighting slavers. Later Britain extended the slave ban globally and began to write anti-slavery clauses into almost all the treaties it signed.

How did that happen?

As Britain, and other western, nations began the early stages of commercialisation and took the first steps toward what would be the development of revolutionary industrial capitalism, conditions were created (reliable trans Atlantic shipping, extended financial systems of credit and trade, the decline and hence shortage of indentured labourers in the new established commercial outposts in the Americas) where a small number of people could make a lot of money by using slavery as part of a trans-Atlantic commercial plantation system of production.

The result was a hybrid form production that involved slaves working in commercial capitalist undertakings. Thus the trans-Atlantic slave trade for a while had a terrible dynamism that tied the dynamics of capital accumulation to slavery.

Only a very small number of British people were involved in the slave trade or the New World slave system of production, and an even tinier number of British owners actually benefited commercially from this slave trade. Just as the horrors of early industrialisation in Britain (child labour, relentless gruelling hours, the creation of urban slums to house the impoverished wage labourers, etc) were the result of the actions of a tiny class of bourgeois owners, and thus not the ‘fault’ of the British people as a whole, so the slave trade was the result of the actions of a small number of British slave owners and not the ‘fault’ of something called ‘Britain’.

Although the income from the slave trade contributed to the process Marx called ‘primitive accumulation’, and thus supplied some of the capital to kick start the industrial revolution, it was not the reason why Britain became so rich and powerful. The industrial revolution occurred in Britain as a result of the unique conjunction of a number of factors but income from slaves was not essential to that process. The industrial revolution would have occurred without slavery and Britain would have grown just as rich and powerful.

The new and surging commercial plantation system of production needed a lot of slaves. The only reliable source of slaves was Africa. But Europeans could not roam about the interior of Africa hunting down and enslaving people. This was because the average life expectancy for Europeans venturing into the interior of Africa at that time was measured in months. It was way too dangerous. The Atlantic slave trade was a coastal phenomena where European slavers could buy slaves in large numbers to ship across the ocean to the plantations. The reason they could so readily buy slaves in large numbers was because Africa was full of well established and large black owned slave empires and trading networks that had been operating long before the development of the Atlantic slave trade. Africa had been the origin of the vast numbers of slaves traded into the Islamic world for centuries before the west coast trade developed. All the enterprising indigenous black African slavers had to do was reorientate part of that trade to the west coast in order to meet the demands of their new customers.

This means that only a small minority of the British and the African elite were involved in the slave trade. Most white Britains and black Africans were not involved in running the slave trade or owning slaves. This also means that therefore skin colour is an inaccurate and insufficient system for identifying ancestral guilt in relation to the slave trade. If you come from a long established white elite family in Britain, or a long established black elite family in Africa (especially from the coastal regions) there is a good chance you have a slaver somewhere in your family tree. Race is not a good indicator of ancestral slave guilt, class is much better.

Although the decision to seek slaves for the new commercial plantation system in Africa was primarily a commercial decision rather than one motivated by racism (a result of the ready supply of slaves in Africa from it’s preexisting internal slave system) the fact those slaves were black was an important and politically convenient factor for British slavers in particular. The rapid rise of the commercial, and then the industrial, bourgeoisie and the rapid growth of a dynamic new capitalist industrial mode of production was underway in Britain, and that brought with it an entirely new conception of citizenship and equality before the law. Already in 1772 the famous Somerset v Stewart law case had led to a ruling by the English Court of King’s Bench that it was not possible to be a slave in England, that if a slave breathed English air they instantly became free. That meant no slavery in England. The need to create a narrative to justify the ownership of slaves outside of England now demanded a politically expedient new ideology that would explain why people in England were all free but that some very rich people from England could still own slaves abroad. That ideology was racism (as a worked up system of ideas rather than as just a personal prejudice) which could be used to justify what a small number of rich British slave owners were doing.

In Britain from the late 18th century a huge mass movement against slavery emerged, this movement was bigger than the Chartist movement and was the largest mass movement in British history. As a result of this massive political campaign the buying and selling of slaves was made illegal across the British Empire in 1807, but because the original caste of British slave owners were very rich and hence politically powerful it took until 1833 before slave owning was outlawed completely as a result of the pressure from the activism of hundreds of thousands of Britains. The 1833 act banning the holding of slaves was part of the same deep political shift that around that time also delivered the Corn Laws and the Reform Act (extending the franchise) and marked the political triumph of a new bourgeoise fraction of the elite linked to the new surging industrial capitalism and the political defeat of that portion of the ruling elite which ran slavery. So the story of slavery and the British was the story of a very small minority that controlled and profited from the slave trade and slave production, and a huge mass movement against slavery by vastly more British citizens which brought an end to slavery.

What should the Left make of all this?

I would argue that to characterise slavery as being something ‘Britain’ did is wrong. If anything, based on the huge discrepancy between the tiny numbers of British slavers and the huge British movement against slavery, Britain was the leading anti-slavery nation. Something we could choose to celebrate or ignore. Using race to allocate ancestral slave guilt or victimhood is also wrong. Slavery was a function of class politics, it was about class power and money. Some very rich Britains did slavery, almost all Britains were not involved. However a very large number of Britains were involved in an ultimately successful political struggle against slavery, a struggle that was critical for suppressing the global trade in slaves. Which part of all that should be emphasised and talked about?

I would argue that rather than Britains feeling guilty about the history of slavery they should be proud that in our nation its citizens rose up and put a stop to slavery.

So by all means take down the statues of actual participants in slavery but lets at the same time put up statues to those British leaders and thinkers, and to the hundreds of thousands of activists, that successfully fought against slavery. Let’s celebrate something that really is great in our history. And while we are at it let’s put up a monument to one of the greatest anti-slavery forces in history, the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron.

Remember when it comes to the nation the Left’s job is not just to tear down but – at the same time – to build up our national cohesion, and sense of national identity, in a new and more progressive form.

Because without the nation there is no progressive project.