Following the referendum result there were a predictable spasm of calls from the good and the great of the EU for the UK to leave as quickly as possible and for the immediate triggering of the formal two year exit procedure of Article 50. These calls for urgent resolution have also been accompanied by many expression of fierce rigidity in the coming negotiations and the declaration of many lines in the sand which cannot be crossed. Sure.

The reality is that following the referendum result the UK can trigger Article 50 more or less whenever it wants, and can if it wants take a very long time indeed to do so. It could even never trigger the final act of exit and instead just keep kicking the can down the road, a stance the EU should be deeply familiar with. I would argue that the longer the delay in triggering Article 50 the better, that at a very minimum it should not happen for a year, and preferably not for several years.

Both the UK and the EU will find any protracted delay testing as it will inject uncertainty into an already fruaght economic, institutional and political situation. Which side finds any delay the most testing will be crucial in determining the balance of power in the negotiations.

There are many sides to this unprecedented and excruciatingly complex situation. Issues of economics, trade and commerce, tangled legal issues and deep political implications both in the UK and in the EU. Here are the thoughts of a few commentators on the factors that will determine if and when the UK triggers Article 50.

To start with here are two different views about the legal, constitutional and political realities of Article 50 from the The United Kingdom Constitutional Law Association.

Nick Barber, Tom Hickman and Jeff King write “Pulling the Article 50 ‘Trigger’: Parliament’s Indispensable Role”

“In this post we argue that as a matter of domestic constitutional law, the Prime Minister is unable to issue a declaration under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty – triggering our withdrawal from the European Union – without having been first authorised to do so by an Act of the United Kingdom Parliament. Were he to attempt to do so before such a statute was passed, the declaration would be legally ineffective as a matter of domestic law and it would also fail to comply with the requirements of Article 50 itself.

There are a number of overlapping reasons for this. They range from the general to the specific. At the most general, our democracy is a parliamentary democracy, and it is Parliament, not the Government, that has the final say about the implications of the referendum, the timing of an Article 50 our membership of the Union, and the rights of British citizens that flow from that membership. More specifically, the terms and the object and purpose of the European Communities Act 1972 also support the correctness of the legal position set out above.

The reason why this is so important is not only because Article 50, once triggered, will inevitably fundamentally change our constitutional arrangements, but also because the timing of the issue of any Article 50 declaration has major implications for our bargaining position with other European States, as we will explain.”

Kenneth Armstrong writes “Push Me, Pull You: Whose Hand on the Article 50 Trigger?”

“The fundamental starting point is that no other Member State and no EU institution has the power to compel the UK to withdraw following the referendum on the 23rd June. This is so for two reasons.

First, the notification under Article 50 TEU is dependent upon a Member State taking a decision to withdraw ‘in accordance with its own constitutional requirements’. Within the UK constitutional framework – and in the absence of anything in the European Union Referendum Act 2015 detailing what the consequence of the referendum would be – the referendum is not legally binding as such. In that sense, and within the UK’s political constitution, it is for the government of the day to act having regard to the will expressed by voters in the referendum. With the Prime Minister announcing his resignation it is, in effect, being left to the new Prime Minister and his or her government to make the withdrawal decision and to notify the European Council in terms of Article 50.

But let’s turn the situation around and imagine that the UK government is keen and ready to pull the trigger on Article 50. Are Barber, Hickman and King right to assert that this cannot be a matter for government alone but something that demands parliamentary authorisation?

Their argument is an intriguing one but I don’t think the claim is compelling. Even without addressing the elegant detail of their argument there is, I think, simply an intuitive point. If, normatively, we think parliament should have the decisive say on whether the UK stays in or leaves the EU, why on earth was that constitutional, as well as normative, principle departed from in entrusting the decision to a referendum?”

Don Quijones at Wolf Street writes “Who Really Holds the Cards in the EU-Brexit Stand-off? Trying to make an example of the UK will likely backfire”

“For the first time ever, the exit door leading out of the European Union is open, albeit slightly. Against all expectations, the UK has somehow managed to jam its figurative foot in the gap between the metaphorical door and its frame. Whether it actually prises the door open or timidly withdraws its foot, only time will tell.

As we warned even before the elections, if the British government fails to honor a majority vote to leave the EU, it won’t be the first time that a referendum in the EU, after people voted the “wrong way,” would essentially be squashed. And if London does manage to pull off a tactical withdrawal from the EU, it’s unlikely to be painless.

The British people may have managed to drown out the constant doomsaying of Project Fear in order to vote for independence from the EU, but the fear and dread are more present than ever as establishment forces on both sides of the English Channel warn of all the imaginative ways in which the EU will seek to punish the UK for its reckless disobedience.

You can hardly blame disillusioned eurocrats for wanting to make Britain suffer for its brazen disregard for European unity, especially as growing ranks of EU members begin entertaining similar ideas of holding their own in/out referendums. To deter other European countries from leaving the bloc, the European Union “should refrain from setting wrong incentives for other member states when renegotiating relations,” recommends one internal German finance ministry document.

The European Commission’s increasingly jaded president, Jean-Claude Juncker, has “insisted” on showing a “tough stance” towards the British government. He has also given members of the European Commission strict instructions not to hold any talks with Britain or visit the country until the U.K. government launches formal proceedings to leave the EU.

But however tempting it may be to make an example out of the UK, it could end up backfiring.

Almost one in three cars sold in Britain comes from Germany, making the British island the biggest export destination for German car producers. It is around a fifth of the total number the industry exports worldwide. In 2015 Britain reached a new peak of 2.6 million car registration, 86% of which were not produced in the UK.

A market of that size would no doubt be sorely missed, especially given that Germany’s biggest car manufacturer, Volkswagen, posted its worst annual loss ever in 2015, having set aside more than $18 billion to address recalls, legal settlements, and other potential penalties resulting from its use of software in diesel-powered vehicles to dupe U.S. emissions tests.

Even in the EU, money does most of the walking and talking. The fact that the UK is a very large net importer of EU goods, especially those made by Europe’s manufacturing powerhouse, Germany, whose economy is already fizzling thanks to a slowdown in China and Western-imposed sanctions on Russia, should give the British government a relatively strong hand in Brexit negotiations, assuming they ever take place.

So just how much economic pain is the EU willing or able to impose on its 27 other Member States in order to make an example of the UK?

Considering that the Greek disaster is still unfolding, Finland’s economy is beginning to wobble, France continues to seethe with strikes and pitched street battles, and Italian and Spanish banks are so crocked that they need constant infusions of cash just to stay afloat, the answer is probably “very little.” In fact, once you drown out all the noise, bluster and propaganda, it’s hard not to conclude that the EU, not Britain, could well hold the weaker set of cards right now.”

The Flip Chart Fairy Tales website has an article entitled “In praise of can-kicking”

“There are plenty of plausible excuses good reasons for putting off Article 50 until at least the spring of next year. Even then, it may be that no-one actually has the bottle to do it. As the ramifications of leaving the EU become clear, the thought of being the politician who took the final decision to wreck the economy might be too much even for Boris Johnson. As Janan Ganesh said, he and Michael Gove looked terrified after the result of the vote was announced:

On the morning after the referendum, the two men wore the haunted look of jokers at an auction whose playfully exorbitant bid for a vase had just been accepted with a chilling smash of the gavel.

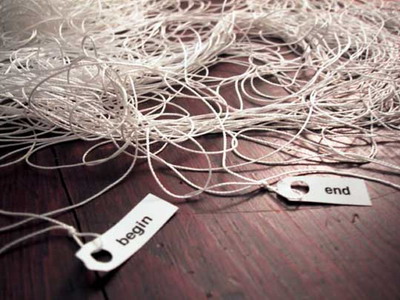

As David Allen Green said last week, the longer Article 50 is put off, the greater the chance that it will never happen.

The fact is that the longer the Article 50 notification is put off, the greater the chance it will never be made at all. This is because the longer the delay, the more likely it will be that events will intervene or excuses will be contrived.

As he said in his FT piece, there is now a stalemate:

Nothing can force the UK to press the notification button, and nothing can force the EU to negotiate until it is pressed. It is entirely a matter for a Member State to decide whether to make the notification and, if so, when. In turn, there is no obligation on the EU to enter into negotiations until the notification is made. There is therefore a stalemate. If this were game of chess, a draw would now be offered.

It is possible, then, that this may simply become a feature of British politics.

It is not impossible to imagine that the Article 50 notification will never be made, and that the possibility that it may one day be made will become another routine feature of UK politics – a sort of embedded threat which comes and goes out of focus. The notification will be made one day, politicians and pundits will say, but not yet.

It’s rather like West Berlin during the Cold War. The longer time went on without a Russian invasion, the less likely it seemed that there would be one, even though the threat was still there. Eventually the city went back to business as usual.”