One of the depressing and sad things about the mess in the eurozone is the way the German people have been manoeuvred into supporting the very system that has suppressed their living standards for over a decade. Maybe that is changing – a bit.

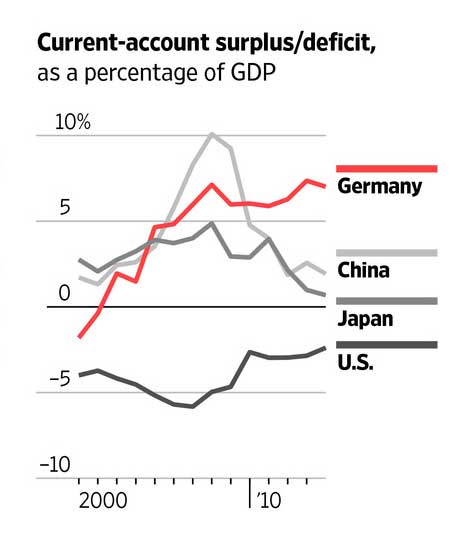

The giant German trade surplus, which has played such large role in destabilising the single currency, is built on the suppression of wages and living standards in Germany itself. The Germany trade surplus, and the suppressed wages it is built upon, sucks demand out of the European, and global, economy. For a while that was balanced by the outflow of capital from Germany into the eurozone periphery where the capital was used to inflate large asset bubbles and fuel debt based spending. When the bubble burst during the financial crisis the eurozone was plunged into a deep recession and the resulting bank bail outs, and in the case of Greece the ruinous level of government borrowing, meant that many eurozone governments now don’t have the fiscal space to reflate their economies. But Germany does. The eurozone largest economy is basking inside an undervalued currency, is awash with savings, has very low unemployment and with a government in the envious position of being able to borrow at negative rates of interest, Germany has the economic weight and the fiscal and trade space to inflate its economy. So far Germany, gripped by Ordoliberal orthodoxy, has resolutely resisted changing course.

The tragic irony of Germany and the eurozone is that the system that is depressing the European economy also means lower living standards in Germany, and that a change of economic policy in Germany and a turn towards inflationary policies would not cost most Germans a penny but would actually make them better off. With a change of economic policy German workers could help the rest of European recover whilst actually increasing their incomes. Unfortunately because the eurozone crisis has manifested itself as a demand for as a series of intergovernmental bail outs Germans, who have seen their living standards stagnate for a decade, have been naturally very hostile to paying other peoples debts and so have supported the very economic policy orthodoxy that is responsible for their stagnant wages in the first place.

But there is some good news in the shape of a rise in German wages. Germany, the biggest economy in Europe and number four globally, is seeing a pickup in growth, and unemployment is near record lows, and rising wages should eventually spur higher consumer spending, more imports and a smaller trade surplus. All that would benefit the eurozone and help the global economy. A bit.

Germany’s metalworkers union IG Metall secured a 3.4% pay increase in February for workers in the Baden-Württemberg region, seen as a bellwether for other deals. Already other German employers have followed suit in raising pay. Germany’s chemical association BAVC agreed a 2.8 per cent pay rise with trade union IG BCE, even though the industry’s output is forecast to contract by 0.5 per cent this year. Unions representing public-sector employees reached favourable pay gains, too. When a recently enacted minimum wage of €8.50 an hour is included, German wages will probably rise 3.5% this year, the biggest jump since the early 1990s.

There are signs that such rises are encouraging German consumers to reach into their pockets. German consumer spending surged in the last quarter of 2014, according to the country’s federal statistics office, outstripping even UK levels, as employment reached a record post-reunification high of 43m.

In a world that is short of aggregate demand, Germany’s trade surplus redirects spending away from other countries, reducing output and incomes abroad. Higher wages in Germany should promote spending by German households on both domestic goods and imports, reducing the imbalance.

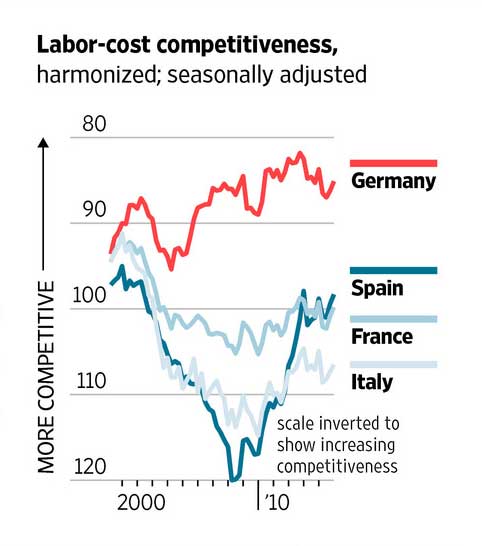

Allowing wages to rise is not a concession by Germany but rather part of what the country signed on to when it joined the euro zone. Germany has been insistent that the so-called peripheral countries increase their competitiveness through slower wages rises or even wage cuts. Wage increases in Germany are an equally important, and symmetrical, part of this necessary adjustment process. Moreover, this adjustment involves no German sacrifices. German firms, which will be slightly less cost-competitive, may export less but they will also see greater demand at home. German workers are unambiguously better off, receiving higher wages commensurate with their higher productivity.