On September 27 regional elections will take place in Catalonia and if the pro-independence parties win a majority of seats in Catalonia’s parliament, they will unilaterally declare independence from Spain. Nearly three months later on 20 December 2015 there will a Spanish general election and recent opinion polls suggest that no single party will gain sufficient votes in December’s elections to govern Spain single-handedly, as the People’s Party has done for the last three and a half years.

Meanwhile Spain, along with Ireland, is held up as an example of the success of austerity, the story told is of a resolute government that (unlike the unreliable Greeks) imposed the necessary tough measures and the result is economic recovery. According to the Financial Times after just over three and a half years of “radical” market reforms Spain is now a lean, fit economic machine:

The FT is not alone in this assessment. At joint press conference with Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy in early September at the German chancellery, Angela Merkel gave Rajoy’s government a ringing endorsement:

When at the same press conference Merkel was asked if Catalonia would be considered outside the EU if it declares independence unilaterally the Chancellor made it clear that she had addressed this issue with Mariano Rajoy and said that “it is in the EU treaties to guarantee the sovereignty and territorial integrity of each state” and said it is “very important that international law is respected and not There is no difference.”

As is the case with just about everything connected to Europe’s slowly unraveling economy, Merkel’s intervention, was wholly politically motivated, something Merkel as good as acknowledged when she stated that Germany has a keen interest in ensuring that Spain’s “economic progress” continues.

Given that recent opinion polls suggest that no single party will gain sufficient votes in December’s elections to govern Spain single-handedly, as Rajoy’s People’s Party has done with ruthless efficiency for the last three and a half years, the German chancellor could end up being disappointed. The two most likely outcomes of December’s general elections are a weak coalition government, at best, or no government at all, precisely at a time when the country’s most important economic region, Catalonia, is seriously considering cutting itself adrift (see below).

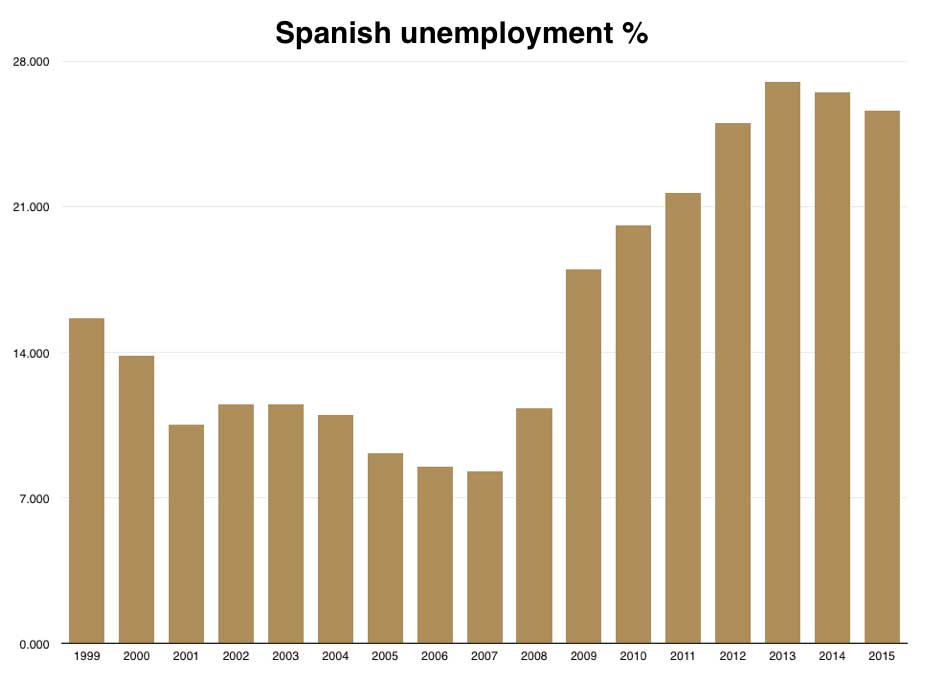

The Spanish success story is like the ‘recovery’ across the rest of the eurozone, fragile and weak. Despite the reforms official unemployment rate is still running at 22% and youth unemployment is an awful 50%. Spanish government official statistics show that Spain’s anemic jobs growth is already showing signs of stagnation. During the month of August the number of unemployed rose by 21,679 people, suggesting, as the Spanish bank BBVA warns (Google translation), that Rajoy’s so-called recovery is already slowing.

Even those fortunate enough to have landed a job are in most cases earning a fraction of what they earned before the crisis. The vast majority of the new jobs are part-time — some lasting only a few days — and they pay poorly, doing little to improve the lives of the millions of Spaniards who lost their jobs during the global economic crisis.

Spain’s Debts

Like much of the eurozone the debt overhang from the eurozone crisis of 2010, which followed the generalised financial crisis of 2008, remains huge and crippling, and the Spanish banking system remains very fragile.

During the pre 2007 boom years very large trade imbalances developed as Germany (and on a smaller scale the Netherlands) drove down domestic wages and drove up exports, at the same time the weaker peripheral countries of the eurozone built up huge deficits as their economies were flooded with cheap German imports. These imbalances grew very large because they were not corrected by currency adjustments now that all the participants in this pattern of unbalanced trade were inside a single currency zone. The trade imbalances were balanced by massive outflows of capital from Germany (mostly via complex conduits in the financial system) and into the deficit countries. In Greece this capital inflow was used mostly to pay for a ballooning public deficit but usually the pattern in the eurozone was that these giant flows of cheap abundant capital fuelled private sector debt and asset bubbles. In Spain this took the form of a giant property bubble.

At the beginning of Spain’s financial crisis, total private (non-financial sector) debt was more than €2 trillion, equivalent to a staggering 220% of GDP. At the same time, total public debt (including all the sort of things that Eurostats prefers to ignore, such as government guarantees, the liabilities of public companies and other forms of public sector debt) amounted to €600 billion, roughly 60% of GDP, one of the lowest levels in Europe. Spanish government debt at the time the financial crisis broke in 2007-8 was lower than German government debt. Like elsewhere in the eurozone, and in the global financial centres of London and New York, all that private debt threatened to bring down a lot banks so a massive bailout program was orchestrated by national governments, the EU and the ECB which saved the banks but caused an explosive growth in public debt. Private debt had become public debt. The proscribed answer to to that, driven by the rigid ordoliberal rulebook of the ECB and eurosystem, was of course austerity.

The result of the bail out program in Spain is that private debt has shrunk to €1.6 trillion (roughly 163% of GDP) while public debt has exploded by €900 billion to €1.49 trillion, an increase of almost 150% in six-and-a-half years. Most of the private debt transferred to the public sector was bank debt, the private debt which was not bailed out was household debt. The bailout was for banks and not for people. Most of the bailout program was implemented under the People’s Party government of the current Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and a large part of that Spanish bailout program was used to pay off the bad loans made by German, French and British banks.

Worse still, despite the hundreds of billions of euros of future taxpayer funds ploughed into recapitalising the private sector – according to the FT, one of the Rajoy administration’s major successes – the amount of bad debt in the system continues to grow and Spain’s bad bank, Sareb, is haemorrhaging funds. If it runs out of capital, it may not be able to keep servicing its huge debt of €45 billion at last count. It just so happens that the guarantor on that debt is … the Spanish state.

Not done with driving Spain’s public debt to record levels, Rajoy’s government also raided the previously well funded Spanish public-sector pension funds in order to fund the Spainish government bailout of the financial sector. Since entering office just three-and-a-half years ago, it has taken €37 billion, roughly half of the total funds, from Spain’s public pension pot. El Economista (Google Translation) warns, if the government were to continue draining the funds at the present, fast-accelerating rate, by 2018 the pension fund reserves will be exhausted.

None of this qualifies as sound, sustainable economic management. The fine-tuning of the government’s accounts to give the appearance that the economy is fully on the mend means the Madrid government can claim things are getting better, which in turn allows Germany and the EU institutions to pretend that the European project is going just fine.

And that is ultimately what successful macroeconomic management is all about in the eurozone today: pretending that everything’s hunky dory while concealing or ignoring all the evidence that proves otherwise and doing absolutely nothing to address the real economic problems, such as poor or non-existent growth, collapsed investment levels, very high unemployment, stagnant living standards, political fragmentation and a dangerously undemocratic EU political system.

Spanish bank’s exposure in Latin America: Santander and Brazil

The already fragile Spanish banking system is heavily involved in Latin America. It is now facing the adverse effects of a significant down turn in business caused by a developing major recession in Latin America centred on a crisis of the Brazilian economy.

On September 12th Brazil’s already troubled economy suffered a major blow when Standard & Poor downgraded the country’s debt from investment grade to junk status. The impact was immediate. Brazil’s currency dropped from 3.78 Real to the dollar to 3.9. It’s currently hovering at 3.88. Just a year ago, when news of the government’s Petrobras scandal began hitting and the economy’s biggest threats – a weakening China, the abrupt end of the commodity super cycle, a strengthening dollar, and floundering internal demand – were beginning to surface, the currency was clocking in at 2.35 Real to the dollar.

In other words, Brazil has lost about 40% of its value against the dollar in the last 12 months. S&P’s latest downgrade could be very bad news for Spain’s biggest bank Banco Santander and all of the other Spanish banks and corporations that have effectively gone all-in on Brazil. For a long time, Grupo Santander’s Brazilian division served as the bank’s biggest global profit centre, but that came to an abrupt end early this year when the group’s UK banking arm overtook it.

Shares at Santander’s Brazilian unit have slipped 15% in Sao Paulo since the end of June. Meanwhile the banking group’s shares on Spain’s benchmark exchange, the IBEX 35, have plunged 23% over the last year. As Bloomberg reports, since early August, the shares of both Santander and Spain’s second largest bank, BBVA, which is particularly exposed to Mexico’s weakening economy, have tumbled more than an index of European bank stocks:

The problem is not just that Brazil’s decade-long phase of of strong economic growth has ended; it is that an extended, deep recession in Brazil is almost certain to drag down much of Latin America with it, a region in which Santander has a vast portfolio of operations, from Mexico in the north to Argentina and Chile in the south. Brazil’s economy represents an impressive 56% of South America’s combined GDP. And it appears to be heading towards its longest recession since the 1930s. To draw a parallel, that’s the approximate equivalent of the economies of France, Germany and the UK plunging deep into recession together. Just imagine the effect that would have on all the other economies in Europe? Given the fragility of the Spanish banking sector the last thing it needs is for its previously main arena of profitability, Latin America, to plunge into a prolonged recession.

Catalonia

September will be a make-or-break month for Spain’s richest region, Catalonia. On September 27, the region will hold its most important elections since the dictator Franco died 40 years ago. If the pro-independence parties win a majority of seats (68 out of 135) in Catalonia’s parliament, they will unilaterally declare independence from Spain. That’s the plan at least, although the chances are that Madrid will have something to say in the matter. And that something is unlikely to be pleasant.

A new poll showed that pro-independence candidates are on course for a slim majority in Catalonia’s regional parliament elections on September 27. In his latest declaration the region’s premier Artur Mas announced the creation of between 50,000 and 70,000 new civil service positions to “cover Catalonia’s new state structures”, which means the Catalonian authorities are already moving to create an independent state apparatus

It didn’t take long for Madrid to hit back, this time with a barely veiled threat from the Ministry of Defense that a military intervention in Spain’s north-eastern province would not be needed “as long as everybody fulfils their duties.” Not exactly comforting.

Madrid has already passed a new national security law that would effectively allow it to take full control of a regional government’s competencies if the central government felt that the administration in question had stepped out of line, either by flouting its responsibilities or breaking the laws of the land (for example, by organising a referendum on national independence). If Madrid were to seize control of all Catalan government and public institutions (including the police), it would be a hugely provocative manoeuvre. Subsequent events could very quickly spiral out of control.

Catalonia is important not just for its relative economic strength, it also has vital geopolitical importance. It is the number-one gateway between Spain and France, accounting for almost all freight traffic between Spain and the rest of Europe. In Barcelona it boasts Europe’s 13th busiest container port. There are also plans to build a strategic gas pipeline through the Catalan Pyrenees, linking the Iberian Peninsula with French and Central European networks. The MidCat pipeline should be operational by 2020 and is expected to reduce Europe’s dependency on Russian gas by 40%, diversifying the EU’s sources of supply.

Concerns about escalating tensions between the central and regional government prompted Catalonia’s largest business association, Fomento de Trabajo, to write an open letter (Google translation) detailing what they see as the risks of secession, including being left out of both the EU and the euro as well as not being able to access financing from the ECB.

But even Catalonia’s business community is riven by divisions on the issue of independence. While many of its biggest companies support Fomento de Trabajo’s opposition to Catalonia’s separation from Spain, many smaller companies have come out in support of independence (Google Translation). They include 13 of the region’s chambers of commerce.

According to Catalonia’s premier, Artur Mas, basic organs and institutions of an independent Catalonian state are now under development.

“One crucial task for the next government will be to create the state structures that will succeed those of the Spanish state: the tax authority, for example, which we have already worked on for the past year and a half, or social security or the central bank,” he told the Financial Times.

In other words, it seems that Catalonia’s pro-independence coalition is now moving inexorably from the realm of slogans and demands, to the realm of determined action. Mas and his colleagues believe that for Catalonia to be a sovereign nation state, it needs its own central bank, but preferably one affiliated with the European Central Bank (ECB).

The ECB seems to be opposing these institutiioanl moves, the chairman of the European Central Bank (ECB), Mario Draghi, has already roundly rejected a petition to turn the Catalan Institute of Finance into an ECB-affiliated central bank. And according to the governor of the Bank of Spain, Luis María Linde, if Catalonia were to declare independence, Catalan-based banks such as CaixaBank, Banco Sabadell and Catalunya Banc would face serious problems and could even go under:

As in Scotland, the separatists and unionists are closely matched in terms of numbers, with roughly two million people on either side. As one side clings to the dream of independence, the other frets about splitting from the rest of Spain, not to mention the potential for economic chaos, social division, and expulsion from the European Union.

Unlike Scotland, the independence process in Catalonia has been banned from taking place. There can be no official referendum or plebiscite, both of which are, in the oft-repeated words of Spain’s incumbent Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, “anti-constitutional.”

One crucial result is that there is no escape valve for the pressures that are slowly building. Nor is there any hope of a negotiated settlement. Instead there is an escalating war of words and gestures, and a generalised climate of uncertainty, resentment and tension.

The economic consequences are already being felt as numerous Catalan companies have recently relocated their head offices to Madrid or other non-Catalan Spanish cities. What’s more, there are signs that the growing tensions between Madrid and Catalonia, combined with rising political uncertainty, are spoiling investor appetite. In June alone, overseas investors withdrew over €21 billion from Spanish markets, compared to the €1.3 billion they injected into the country during the same month of 2014. Not good news for the fragile Spanish banking system.

Eurozone fragility

After the 2010 eurozone crisis the ECB and used a series of program, including quantitative easing, to successfully stabilise eurozone government bond rates (except for Greece whose bonds were not supported by QE). This was very important because back in 201-11 the sharp rise in the cost of issuing new government bonds for indebted countries like Spain, Italy and Portugal threatened to make their large debt mountains rapidly unsustainable. The ECB program was successful and bond rates fell and more less harmonised across the eurozone (except for Greece) but now the rates that different countries pay is separating again as it did in the build up to the 2010 crisis and as a result Spainish debt servicing is becoming more expensive.

Concerns about continuing economic and banking facility as well as concerns about a possible break up of Spain should Catalonia vote for independence are beginning to show in the performance of Spanish bond yields. The political instability gripping the nation is undermining investor confidence even after signals from ECB President Mario Draghi in early September that asset purchases could be extended if Europe’s economic and inflation outlook continues to deteriorate.

“These moves have some more to run in the coming months, as elections approach,” said Jan von Gerich, chief strategist at Nordea Bank AB in Helsinki. “The main opposition parties are campaigning for a reversal of the earlier reforms. Forming a government will be very hard.”

In other words, the same thing that happened in Greece after Syriza’s victory at the beginning of this year is now beginning to happen in Spain, the nation’s debt is becoming more costly as jittery investors desperately look for other places to park their cash, at least until tensions die down. One of the biggest beneficiaries so far has been Italy, whose 10-year bonds recently widened the spread on their Spanish counterparts to 25 basis points, the highest premium since August 2013 on a closing-price basis.

This represents a fairly significant shift given that at the end of 2014 Spanish 10-year bonds were 28 points lower than their Italian equivalents and even as recently as mid-July Spanish yields were below Italy’s. According to Nordea’s von Gerich, the yield gap may widen further, to 50 basis points, if campaigning gets more heated and the polls get closer.

Even Portugal’s bonds have fared better than Spain’s in recent days, despite the fact that it, too, has fractious elections coming. Spain’s risk premium, the spread between the 10-year Spanish government bond, and the benchmark 10-year German bond (bund), has widened from 107 to 139 basic points since the end of 2014 and is now back above the long-term average. Even Spain’s benchmark index, the IBEX 35 which is the official index of the Spanish financial market, is down 17% from its ECB quantitative easing supported high in mid-April.

Three Long Months Ahead

The markets are not just worried about the dangers posed by Catalonian independence and the prospect of a potentially standoff between Madrid and Barcelona; they are also concerned about the spectre of political instability resulting from inconclusive general elections in December.

In other words, at a time when the country’s biggest economic region is threatening to sever the cord, plunging the country into a constitutional crisis of unprecedented dimensions, a general elections looms that may well lead to either a desperately weak coalition government or no government at all.

And underpinning the political problems is the fact that in a period that is officially characterised as a recovery, and in the economy held up as the shining example of what the standard officially sanctioned eurozone austerity program can achieve, mass unemployment has become the new normal.

As has been the case several times before in the eurozone if markets continue to vote with their feet by selling Spanish bonds, they could end up achieving the exact opposite of what most market participants actually want, i.e. they could end up fuelling uncertainty rather than ensuring stability.

Heightened uncertainty and economic weakness at this stage in the game could well backfire. It would almost certainly hammer the final nail in Rajoy’s coffin. After all, the only remotely positive thing that his scandal-tarnished administration has actually done over the last four years is to temporally and partially drag Spain’s crisis-economy out of the hole it was in, at great cost to Spanish taxpayers, businesses, workers, and pensioners.

Rajoy calls it a virtuous circle. But even with near-zero interest rates for the foreseeable future, that virtuous circle could very quickly come to a standstill, or revert to a vicious one, especially with global macroeconomic conditions deteriorating and the most important source of Spanish corporate profits, Latin America, on the verge of a major recession.