The outcome of the recently negotiated, and only interim, deal between Greece and the Troika has been to suck liquidity and confidence out of the Greek economy. This is the exact opposite of what it needs. Unemployment rose to 26 percent in December, in its first monthly increase since September 2013. Meanwhile just as government finances take a turn for the worse Greece needs to refinance or repay about 6.5 billion euros ($7.2 billion) in debt and interest in the next three weeks, including treasury bill redemptions. To top that, its budget forecasts a 2.1 billion euros cash deficit in March. A tax-revenue shortfall opened a hole of 217 million euros in January, derailing budget targets.

Greece needs to refinance treasury bills totalling 1.6 billion euros next week, and pay about 420 million euros in IMF amortisation and interest on its debt. The bill rises to 3 billion euros the week after, of which 913 million euros are due to the IMF.

The Greek government has so far been covering its cash deficit by tapping the reserves of public entities, including pension funds, hospitals, and universities. It has also rolled over treasury bills which means selling new treasury bills to pay for the old ones that are expiring and being redeemed. The dependency of the Greek government on further treasury bill sales to prevent a government insolvency puts Greek banks in a very difficult position: either they buy Greek Bonds which, because they are not resell-able, reduces the banks liquid assets and thus undermines their solvency – or let the Greek government go bust precipitating a Grexit with unknown but probably very unpleasant consequences.

Adding to the pressure on the already very weak Greek banking system is the fact that following the Syriza election victory the European Central Bank (ECB) stopped buying Greek government bonds from Greek banks, which is what it does for all European banks suffering liquidity problems (and there are plenty). This was done to put pressure on the political negotiations that were underway between the new government and its creditors. The withdrawal of ECB support combined with the massive capital flight, caused by anxious Greeks moving their Euros abroad in case of Grexit, means that most Greeks banks are insolvent and are being propped up by weekly tranches of ECB Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA), a funding stream that can be turned off at a moments notice.

Having lost access to market sources of financing, Greece’s only lifeline is emergency loans extended by euro-area member states and the International Monetary Fund. Failure to secure an agreement with them on the disbursement of funds has triggered a liquidity squeeze, raising doubts about the country’s solvency, and further damaging any economic recovery.

I still think disorderly Grexit is quite possible.

Click here to see the Greek Debt Clock and watch its deficit grow in real time.

The EU turns the screws on France

The EU turns the screws on France

French GDP rose by just 0.4% during 2014. The French economy, the second largest in the eurozone, grew by just 0.1% in the last three months of 2014. Business investment contracted again, showing French firms remain nervous and unwilling to spend.

Demonstrating a brilliant grasp of macroeconomics the European Commission ruled that France’s budget for 2015 would not be enough to achieve a reduction of 0.5 percentage points in the deficit this year, and demanded a further four billion in savings, and gave France two years to bring its deficit under the limit of three percent of GDP, but set strict levels that must be achieved along the way.

On Wednesday European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker told Spanish daily El Pais that while Paris had undertaken spending cuts and structural reforms, those “have not been ambitious enough.” He also noted that France could yet be fined if it fails to continue reforming and reigning in its deficit.

“I’m sure the French government has understood that penalties remain a possibility,” Juncker said, adding France “knows it must do better, and it will.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel noted that France seemed to be going in the right direction.

“I think France is very much on the right track,” she said.

“We are going to be working very closely with France in support of these efforts.”

Paris will also have to submit regular progress reports as Brussels exercises its new powers to oversee member state budgets.

Click here to see the French Debt Clock and watch its deficit grow in real time.

In response to the same new European Commission budgetary review powers that led to the demand for France to cut its spending Italy has just promised to reduce its structural deficit by 0.3 percent. Matteo Renzi’s government pledged to find an additional €4.5 billion of savings, with €3.3 billion coming from a cash reserve that had previously been intended to fund tax cuts to help meet the EU budget requests. A further €1.2 billion will be made from adjusting its spending plans.

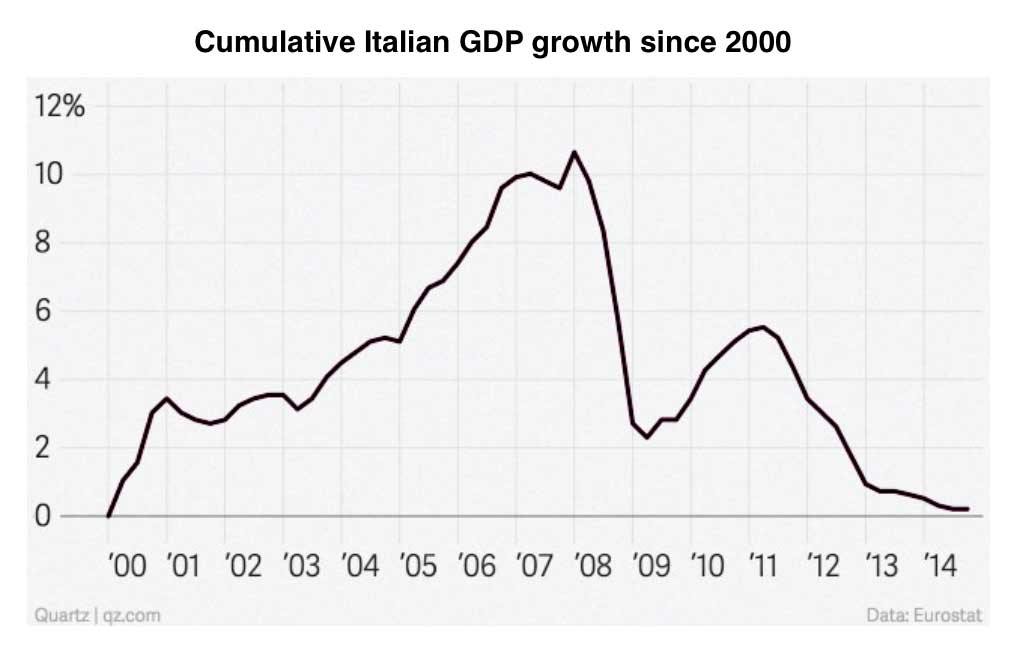

Italy’s economy, the third largest in the eurozone, had been shrinking since mid 2011, its longest recession on record. In that context, stagnation is something of an achievement. But it won’t do anything to claw back the ground lost since the global financial crisis. The Italian economy is essentially the same size as it was in 2000. Italy is currently facing its worst recession in recent history, having lost about 8.5% of GDP between 2007 and 2013. The current situation is, to a large extent, the result of the Eurozone crisis and of the tough fiscal-austerity measures introduced across Europe, and particularly in Italy.

When the housing bubbles that were driving the euro zone economies burst in 2008, there was nothing to replace this source of demand. Italy joined other countries in the euro zone and around the world in using fiscal stimulus to boost demand, but then was forced to revert to austerity in 2010.

Its economy has been shrinking ever since, as would be predicted by textbook Keynesian economics. GDP in 2014 is projected to be almost 9.0 percent less than the 2007 peak. According to the IMF’s projections, which have consistently been overly optimistic, Italy’s GDP will still be 3.5 percent below the 2007 level in 2019. This would imply twelve years with cumulative negative growth, a performance far worse than any major country saw in the Great Depression.

The shrinkage of the economy has been disastrous for Italy’s workers. The employment rate for prime age workers is down by almost six full percentage points. The employment rate for young people is down by ten percentage points, translating into youth unemployment rates of close to 40 percent.

Of course the pain for workers is the strategy. The plan designed for Italy by the European Commission is to have Italy regain competitiveness with Germany by forcing down wages. A prolonged period of high unemployment is an essential part of this process.

Meanwhile Italian government debt is 131.80% of GDP and it has increased by 65098 million euro in the last year.

Click here to see the Italian Debt Clock and watch its deficit grow in real time.

Click here to see the UK Debt Clock and watch its deficit grow in real time.

Click here to see the UK Debt Clock and watch its deficit grow in real time.