I was wrong about Jeremy Corbyn. I thought until quite late in the election campaign that his leadership would result in electoral disaster for the Labour party. The fumbling and accident prone opening period of his leadership, the apparent collapse of support in the parliamentary party, the vacuous position of the Labour leadership during the Brexit campaign which allowed the referendum to become a debate inside the Tory party, and the terrible results in the Scottish and recent local elections all convinced me that come a general election the Labour Party would be obliterated. It wasn’t and I was wrong about that. Corbyn has changed the balance of power in the UK and I applaud him for that.

Corbyn actually grew in stature throughout the campaign and managed to galvanise a surge of youthful (and not so youthful) activist enthusiasm. The result was a new form of leftist populism and a tremendous blow to the Tories which has changed the balance of politics in the country. It makes you wonder how Saunders would have fared against Trump. ‘Dare to struggle dare to win’ indeed.

Now comes the tricky part. Corbyn has to hold together his electoral base and heal – generously – the divisions inside the Parliamentary Labour party. The opportunities for making mischief with the Tories in the House of Commons are there for the taking, and with astute manoeuvres it should be possible to win majorities for specific Labour Party policies. The DUP for example were committed to maintaining the pensions triple lock and winter fuel payments, both of which the Tories wanted to tear up, and the DUP manifesto said this: “Prioritise spending on our Health Service, create more jobs and increase incomes, protect family budgets, raise standards in education for everyone and invest in infrastructure.” The DUP’s top three priorities were listed in its manifesto as being “1. More jobs and rising incomes 2. A world class health service 3. Education – every child the opportunity to succeed”. The DUP also favours a soft Brexit. The agreement between the DUP and the Tories is not a coalition but a ’Supply and Confidence’ agreement which means the DUP can, and will, vote against the government on specific issues without breaking the agreement. This will create ample opportunities for the Labour Party to engineer some policy victories in the House of Commons, but that will require the PLP and the party leadership, in particular the Leaders office, working closely together.

Probably the best outcome will be if this Tory government clings on for another couple of years through what is likely to be a down turn in the economy, stagnating living standards and a devilishly complex and difficult Brexit which will stress all the Tory Party’s internal fault lines. If all goes well then Labour could win the next election and what seemed until couple of weeks ago the utterly unlikely prospective of Corbyn in Downing Street might actually come true.

What then? Well as Ben M’Hidi says to Ali La Pointe in The Battle of Algiers: “it is hard enough to start a revolution, even harder to sustain it, and hardest of all to win it, but it is only afterwards, once we’ve won, that the real difficulties begin”

Leaving aside what the contents of a successful and effective Labour Government reform program might look like – and that in itself is a huge topic – it is important to understand some of the constraints that all western liberal democracies now operate under. An important analyst in this area is Wolfgang Street and his theories of what he calls the ‘European Consolidation State’.

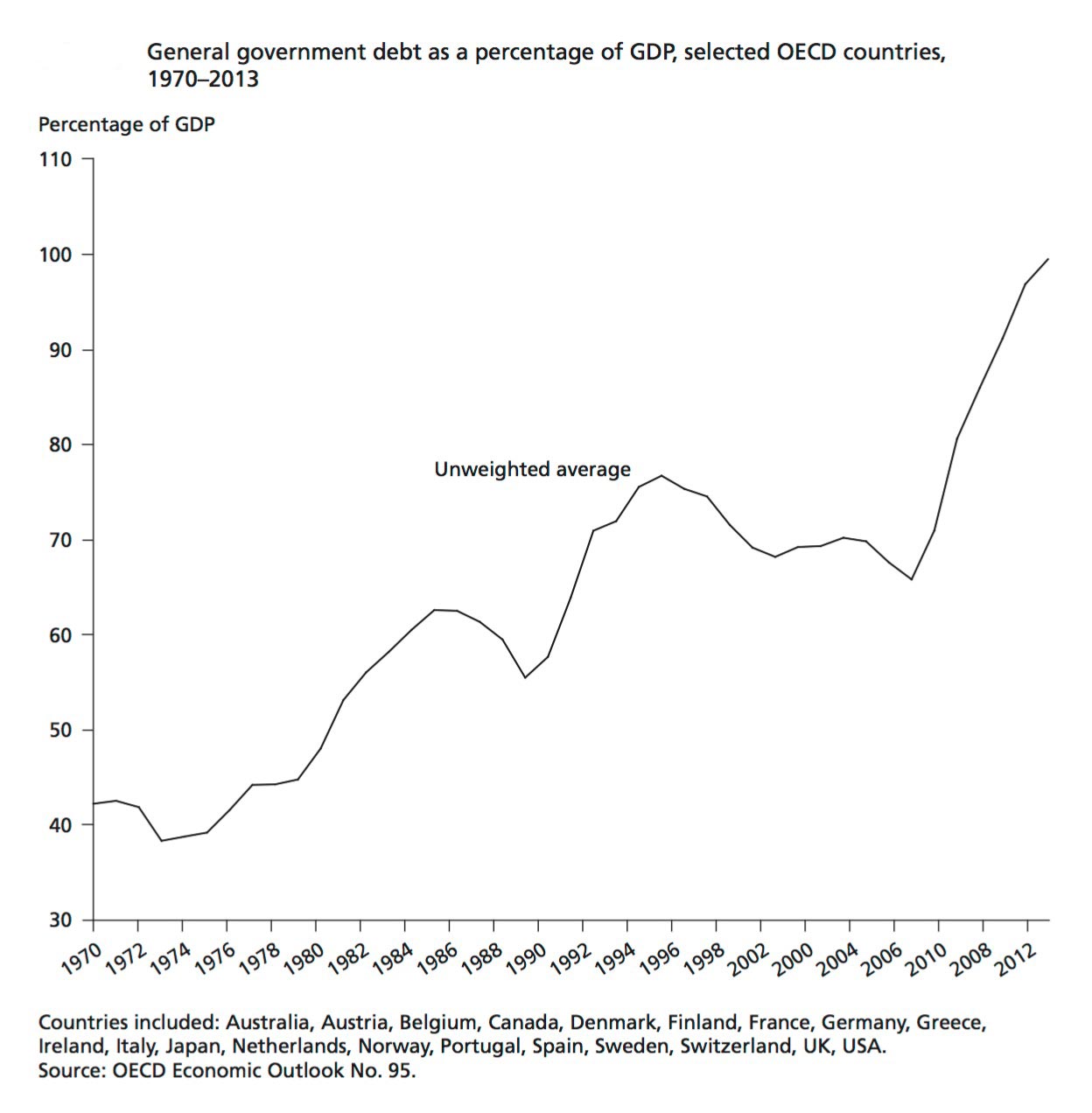

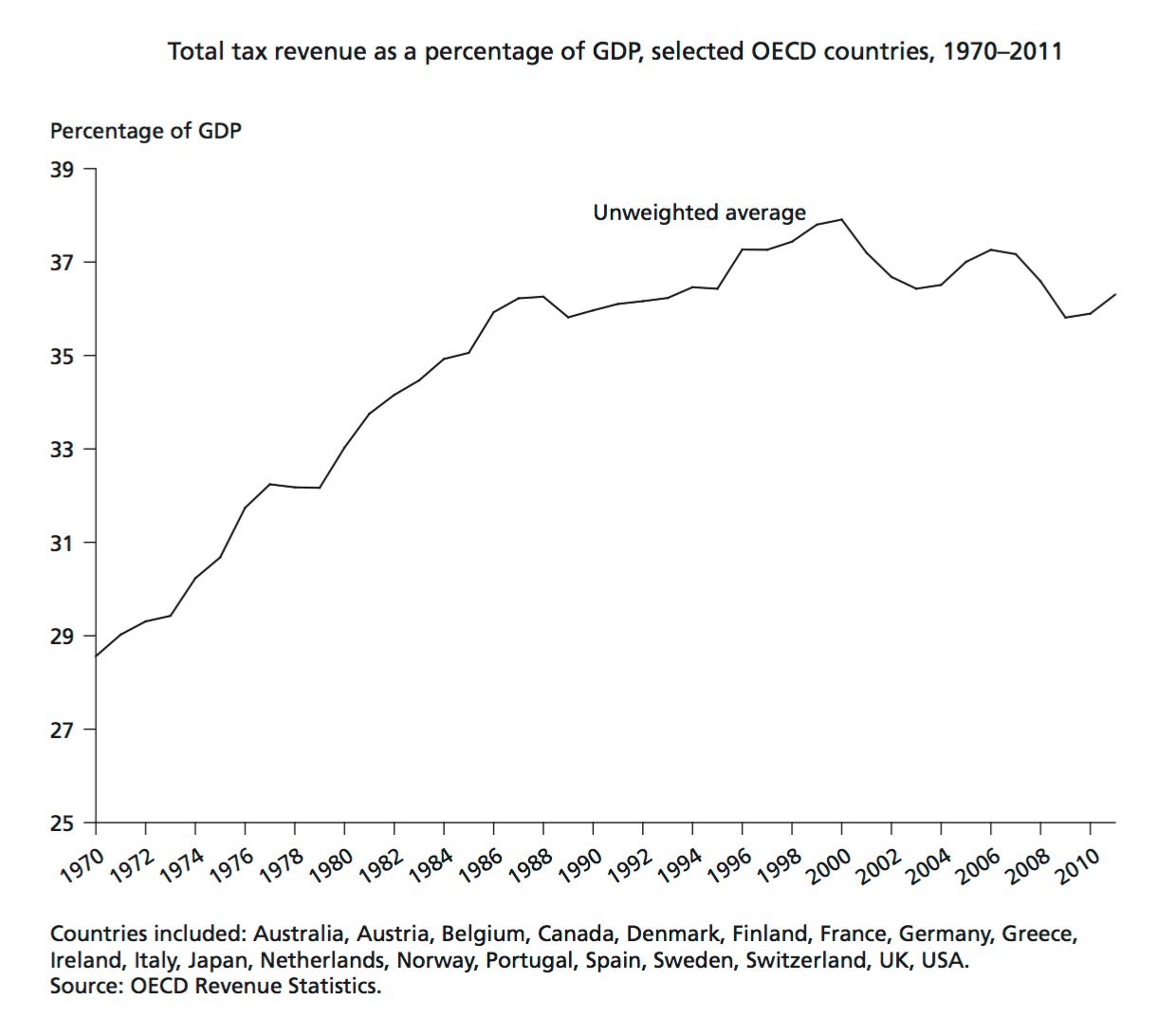

Streek explained his concept of the consolidation state as follows: “The rise of the consolidation state follows the displacement of the classical tax state, or Steuerstaat, by what I have called the debt state, a process that began in the 1980s in all rich capitalist democracies. Consolidation is the contemporary response to the “fiscal crisis of the state” envisaged as early as the late 1960s, when postwar growth had come to an end. Both the long-term increase in public debt and the current global attempts to bring it under control were intertwined with the finanancialisation of advanced capital-ism and its complex functions and dysfunctions. The ongoing shift towards a consolidation state involves a deep rebuilding of the political institutions of postwar democratic capitalism and its international order. This is the case in particular in Europe where consolidation coincides with an unprecedented increase in the scale of political rule under European Monetary Union and with the transformation of the latter into an asymmetric fiscal stabilisation regime.”

Streek makes a convincing case that the long term deterioration of public finances and the steady and large rise in public debt means that there is now in western democracies two constituencies, citizens and creditors – or two peoples, a Staatsvolk and a Marktvolk. Debt states have to be loyal to both, with the two struggling over who is to be the principal stakeholder and who, in a fiscal crunch, has to give. As Streek says: “The consolidation state settles that struggle in favour of its second constituency, its Marktvolk, by firmly internalising the primacy of the state’s commercial-contractual commitments to its lenders over its public-political commitments to its citizenry. In a consolidation state, citizens lose out to investors, rights of citizenship are trumped by claims from commercial contracts, voters range below creditors, the results of elections are less important than those of bond auctions, public opinion matters less than interest rates and citizen loyalties less than investor confidence, and debt service crowds out public services.”

The democratic debt state and its two peoples |

|

|---|---|

| Staatvolk | Martvolk |

| National | International |

| Citizens | Investors |

| Civil Rights | Contractual Claims |

| Voters | Creditors |

| Elections (periodic) | Bond Auctions (continual) |

| Public opinion | Interest Rates |

| Loyalty | 'Confidence' |

| Public Services | Debt Service |

What this means in practice for an incoming Labour Government is that it will be extraordinarily vulnerable to the verdicts and actions of the financial markets. Although it is true that the burden of the deficit and public debt has been vastly exaggerated by the Tories in pursuit of an ideologically driven desire to shrink the state it is also true that the entire viability of UK public debt management now hinges on the issue of government bond yields. At the moment the cost of government borrowing is historically low. This is important because all government debt has to be rolled over, that is as old bonds fall due and are redeemed then new bonds have to sold to finance that process. If existing public bonds (which are being traded constantly in the market) are sought after then their price will rise and their yields will fall, and this means that new debt – newly issued bonds – can be successfully auctioned off in the market at a lower rate of interest. The inverse is also true, if existing UK government bonds are not selling well in the market, then their price will fall and their yields will rise, and that means new bonds can only be successfully sold by increasing their rate of interest. The upshot of all this is that it doesn’t take much of a shift in the financial markets for the interest rate on UK government debt to rise and for the overall level of debt to begin to balloon. Once that happens the whole process takes on a terrible feedback loop and quickly the government is in a deep financial and fiscal crisis. It’s this power of the markets to out vote citizens in heavily indebted states that Streek is referring to in his Consolidation thesis.

In theory faced with rising yeilds and a possible debt/fiscal crisis the Bank of England could resume its Quantitative Easing (QA) program whereby it buys government bonds in the market place using newly created money. Theoretically this should push up demand for bonds and therefore push down yields but a resumption of QA might be taken as an emergency response and as a sign of weakness in UK public finances and thus might cause a greater loss of confidence in the markets. Again theoretically the Back of England could just take it upon itself to buy up government debt thus replacing the market (see this article I wrote earlier on the topic) but no one knows what the limits of QA really are so we would be entering uncharted territory. Plus of course the Bank of England is independent and may decide not to rescue a Labour Government.

The reasosn I am writing all this is to make it clear that it is not just a question of a Labour Government winning an election committed to delivering a well contructed reform program, modern financialised capitalism now contrains national government very directly and are a very powerful factor in the equation.