While looking at various information sources about Greece I came across some interesting data which I want to share, and which it is worth bearing in mind as we look at whatever new reform program Syriza eventually implements if they succeed in getting some sort of deal on debt. Remember that Yannis Varoufarkis said that one of the three top priorities for the Syriza government was to “smash up the Greek oligarchy system”.

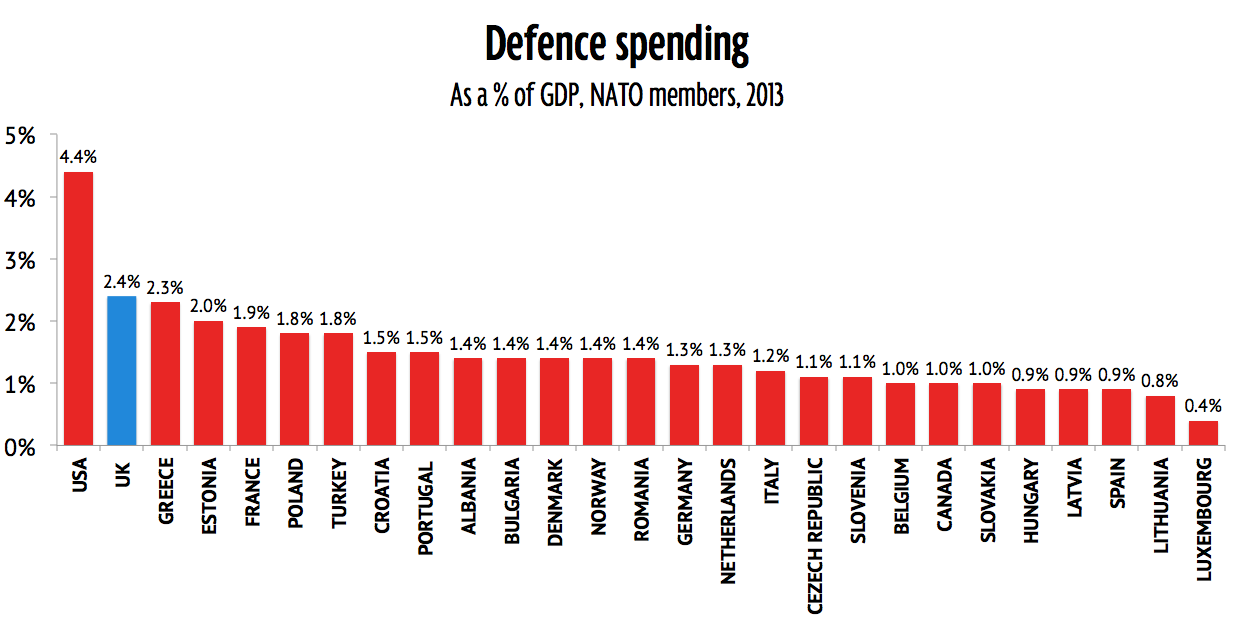

Greek military spending is bonkers

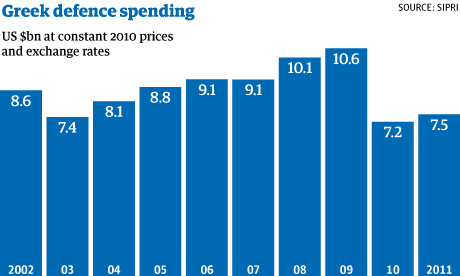

From 2002 to 2006, Greece was the world’s fifth biggest importer of conventional weapons! Greece, with a population of just 11 million, was the largest importer of conventional weapons in Europe and ranks fifth in the world behind China, India, the United Arab Emirates and South Korea. In 2012 it was still the 10th biggest importer of conventional weapons. Its military spending is the second highest in the European Union as a percentage of gross domestic product. Excessive military spending was one of the factors behind Greece’s stratospheric national debt. The country has cited perceived security risks from Turkey and, in addition to state-of-the-art submarines, has bought hundreds of Leopard tanks, howitzers, Mirage fighter planes and F-16 jets from Germany, France and the US since the late 1990s.

This is obviously bonkers. It’s not just me who thinks that. In late April 2010, Stelios Fenekos, a 52-year-old vice admiral of the 22,000-person strong Greek Navy, resigned his position, bringing a three-decade Navy career to an end. He says he did so to protest the Greek defense minister’s decision to purchase the subs, as well as other decisions taken in recent months that Mr. Fenekos considers “politically motivated.”

“How can you say to people we are buying more subs at the same time we want you to cut your salaries and pensions?” says Adm. Fenekos, in an interview with a reporter. He was referring to the government’s 5% cut in most pensions and even deeper slashes to public-sector wages enacted in response to the crisis. The Greek Navy, he says, cannot afford to maintain the additional submarines.

The Troika reform package includes cuts to the the defence budget but the budget still remains disproportionately large for such small and relatively poor country. Even with the cuts, its military budget accounts for nearly 4% of national economic output, compared with the eurozone average of around 2%.

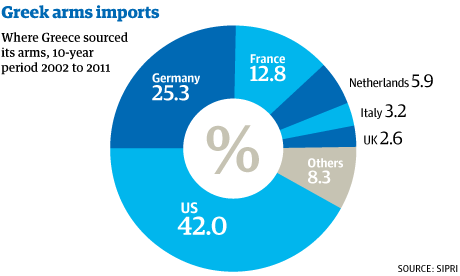

The biggest suppliers of military equipment are the USA (42%), Germany (25.3) and France (12.8%).

Since the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus, Greece has spent an estimated 216 billion euro on armaments. That’s the official figures but it is widely understood that a lot of Greek military spending was ‘off-the-book’ and deliberately hidden. Part of the reason for this is to protect extensive corruption in Greek military procurement. In 2012 the former defence minister Akis Tsochadzopoulos was jailed on charges of accepting an 8 million euro bribe from Ferrostaal, the German company that helped oversee the scandal-marred sale of four Class 214 submarines to the Greek navy in 2000.

In this context the appointment of Panos Kammenos, the leader of the right-wing nationalist Independent Greeks (ANEL), as Ministry of Defence is significant and may mean that Syriza will delay reform of the military until a later date, possible to head off any possible military coup such as the one in 1967 that toppled the last leftist Greek government. Kammenos has built close links to the military in recent years and demanded ANEL be given control over defence during the talks to form the coalition.

Greek social expenditure

According to OECD figures for social expenditure as a percentage of GDP, Greece spent 10.3% in 1980, 19.3% in 2000 and 23.5% in 2011. The equivalent figures for Germany are 22.1%, 26.6% and 26.2%. The EU average in in 2011 was 24.9%. When it comes to social spending, far from being bloated, Greece has only just caught up.

Greece spent less on education, health and social protection than the EU-15 over the 1995-2012 period, but spent considerably more on interest payments (6.9% compared to 3.5% for the EU-15), general public expenditures – judiciary, police, administration costs etc (12.2% compared to 7% for the EU-15), and defence expenditures (2.9% compared to 1.6% for the EU-15). Where there is ‘bloating’, it is the bankers and the state who benefit.

The Greek problem is tax collection rather than excessive spending

Data from Eurostat comparing averaged values as a percentage of GDP for public expenditure, taxes and deficits between 1995-2012 for the EU-15 and Greece shows clearly that the major issue in Greece is on the revenue side, not the expenditure side.

The Greek average for government expenditure, at 48.7%, is only 0.6% higher than the EU-15 average. However, the Greek figure for government revenue is 3.6% below the EU-15 average. The Greek budget deficit average is 4.3% higher than the EU-15 average. So it is quite clear that the Greek budget deficit is driven by a relative shortfall of revenue rather than an excess of expenditure when averaged out over the 1995-2012 period and compared with the fiscal regimes of the other EU-15 nations. Far from being ‘bloated’, she is ‘underfed’.

Why is Greece so poor at collecting taxes? In 2011, Professor Friedrich Schneider of Linz University estimated that in 2010 the Greek black economy was worth 25.5 % of GDP (compared to 10.7% in the UK, 13.9% in Germany, 19.4% in Spain and 21.8% in Italy). The spread in the relative size of the black economy across European countries is commonly linked to variations in levels of self-employment. In 2013, according to Eurostat, Greece had the highest rates of self-employment in the EU (31.9% compared to an EU average of 15%). Next highest is Italy at 23.4%. The main structural factor behind varying levels of self-employment in the EU is the size of the agricultural sector and the nature of rural property ownership – in other words, levels of self-employment are related to the size of the agricultural and rural petit-bourgeoisie and modes of rural property ownership. Far from being the result of some uniquely Greek or welfarist propensity to corruption, the low levels of tax collection in Greece stem from well known structural determinants.

It seems then that if ‘clientelism’ is a factor in Greek fiscal woes, then the major ‘clients’ are the elements in the professional and agricultural petit-bourgeoisie who don’t pay their taxes, the civil service, the army and the overseas banks – not organised labour, the public sector, the unemployed, the sick and the elderly. While it is true that the latter have increased their ‘share of the pie’ since 2000, this has been in line with EU trends. Between 1990-2011, social expenditure as a percentage of GDP across the EU-21 rose from 20.6% to 24.9%. In the UK it rose from 16.7% to 23.9%. In France from 25.1% to 32.1%. While in Greece it rose from 16.6% to 23.5%.

Interestingly Hans-Werner Sinn, an impressive German economist who tends towards the austerian side had this to say in his brilliant (but dense and demanding) book ‘The Euro Trap’

“Greece has a huge current account of deficit in agricultural products, which, considering its nearly ideal climate and the huge relative success of Israel [in agiculutual production], which certainly enjoys no better conditions, seems downright preposterous. Its imports of agricultural goods exceed exports by one and half times. The country even imports tomatoes from the Netherlands and refined olive oil from Germany.“