Researchers Sascha Becker and Thiemo Fetzer, are presenting an interesting paper at the Royal Economic Society’s annual conference at the University of Bristol in April 2017 entitled “Does Migration Cause Extreme Voting?”

The paper makes a persuasive case for the argument that it was the special social shock of the post accession low skilled migration from Eastern that caused the surge in UKIP support and eventually the Brexit vote.

The ‘Freedom of Movement’ was included in the ‘four freedoms’ in the Treaty of Rome in 1957 largely for symbolic reasons, and to offer something to the Italians (who were the East Europeans of those days). It was never envisaged that it would become the basis for a mass movement of workers from poorer to richer countries as it did after 2004, partly because it was always assumed that member states would be at similar levels of economic development. Neither were the stark polarisation of economic performance and employment levels created by the post 2008 single currency area foreseen. It is worth noting that the freedom of labour mobility is often confused with the freedom to move around Europe visa free with minimal documentation or obstruction. The freedom for citizens to move across borders or to study in other members states is perfectly compatible with a system that imposes greater controls or management on the freedom to work in other member states and the initial commitment in the Treaty of Rome to freedom of movement was viewed as a travel liberalisation project rather than an opening of labour markets to mass migratory flows.

The distinction between citizen and worker is crucial here. Prior to 1992 it was ‘workers’ that moved to work in other member states not ‘citizens’, meaning that migratory workers did not expect and were not offered automatically the same rights as national citizens, and they usually had to have a specific job offers in order to gain work in another member state.

During the golden age of post-war economic growth for the European economy there was relatively little movement between countries, a few Italians moved to Belgium and Germany, and later there was an Iberian flow into France but as the poorer countries got richer the flows trailed off. In fact labour flows between member states remained negligible for about half the life span of the single market.

Accession and the recent step changes in migration flows in the UK

The 2004 enlargement of the European Union was the largest single expansion of the European Union (EU), in terms of territory, number of states, and population to date. It occurred on 1 May 2004.The following countries (the so called ‘A10’ countries) all simultaneously joined the European Union: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

After the 2004 EU enlargement to Eastern Europe the Labour Government enthusiastically embraced the principle of the free flow of labour. While most continental European countries successfully lobbied for phasing in the common market’s free movement of labour, the UK was among the few countries to permit access to its labour market to East Europeans from day one. Austria and Germany, in contrast, only opened their labour markets to migrants from Eastern Europe seven years after the EU enlargement.

In the build up to the 2004 accession the Home Office computed different scenarios of expected migrant numbers from Eastern Europe to the UK but were working under the assumption that other big EU countries, in particular Germany, would open up their borders as well. In fact unlike the UK the other big labour markets in the old EU mostly shut their borders to workers from the accession countries.

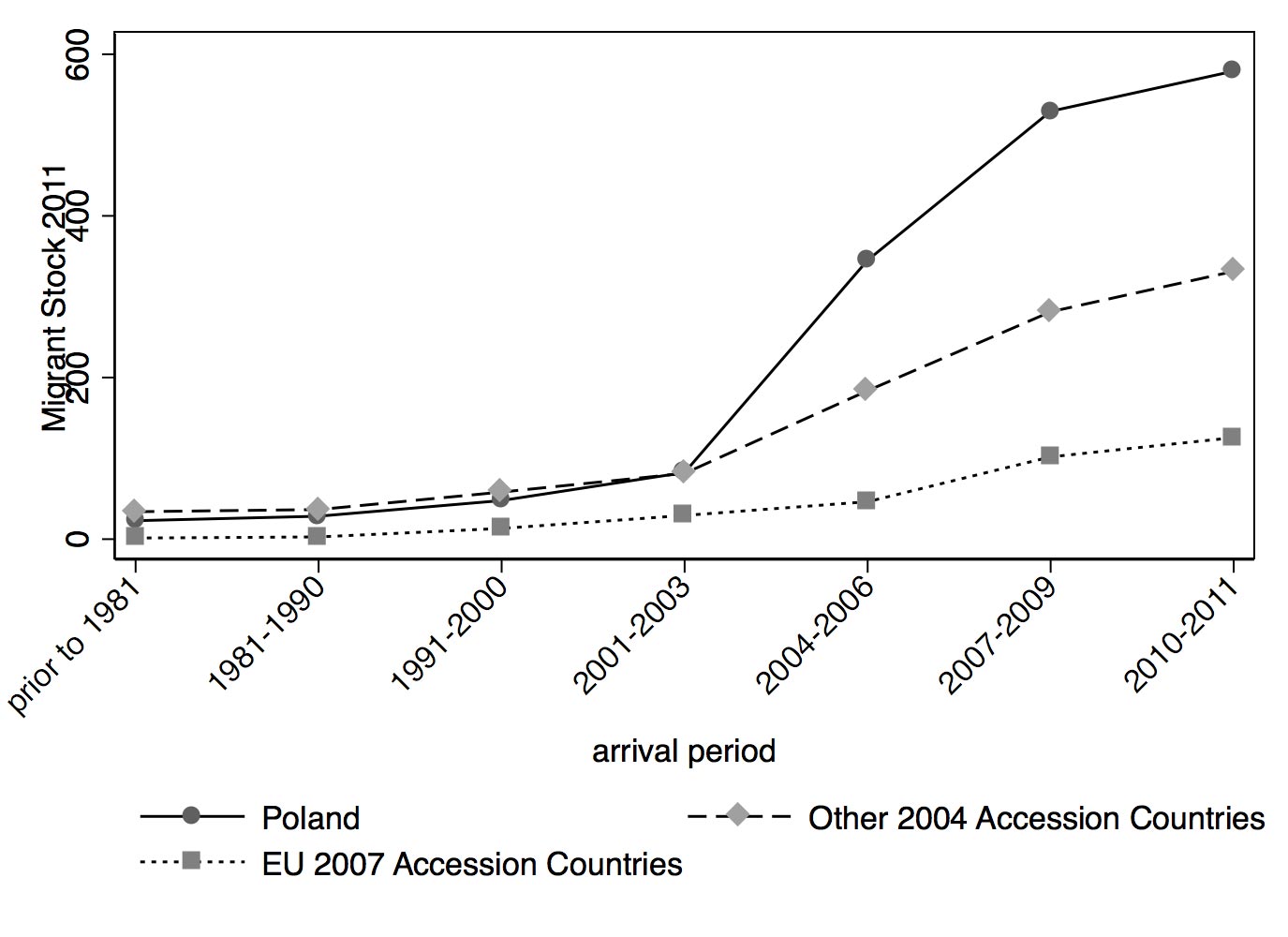

Based on the false assumption that other large labour markets would be opened to workers from the ‘A10’ countries the Home Office calculated that only around 5,000-13,000 East Europeans would arrive in the United Kingdom per year. In fact at least 850,000 people (around 3% of the 2001 UK working age population) migrated from Eastern Europe to the UK between 2004 and 2011.

The UK wasn’t the only EU member state to experience post 1992 migratory labour flows but the flows into the Uk were the largest. By 2014 around 3.5 percent of the EU population was born in another member state compared to just 1 percent in 2000. In the UK the figure was just over 6 percent and EU citizens accounted for about 8 percent of low skill jobs. There are just over 1 million UK citizens currently working or resident in other EU countries compared to 3.3 million EU citizens working or resident here. If one takes out the number of non-working UK citizens living in other member states compared to non-working EU nationals living in the UK (given that few EU citizens will be retiring to the UK because of its weather) then the labour market imbalance in the migratory flows into and out of the UK are even starker.

In many senses the UK became the EU’s employer of last resort, soaking up the labour of the depressed eurozone periphery. The UK has several key attractors for those looking to travel to work: a relatively strong demand for labour and a higher than EU average level of growth (due to being outside the Eurozone), the absence of intrusive documentation systems such as ID cards meaning casual and informal work can flourish, a pre-existing tolerant and liberal attitude to foreigners and ethnic minorities, and the convenience of English (the global language) being the native tongue. In addition to the migratory flows from the EU there were non-EU inflows. The share of foreign-born persons in total employment increased from 7.2 % in 1993 to 16.7% in 2015, or around one in six.

The increase in the share of foreign-born workers in employment in the UK has been highly differentiated across occupations and sectors. Although foreign-born workers have been and remain employed in a wide range of jobs, the growth in employment shares of foreign-born workers in recent years has been fastest among lower-skilled occupations and sectors. In 2002, there was only one low-skilled occupation (food preparation trades) in the list of top ten occupations with the highest shares of foreign-born workers, now there are at least five low-skilled occupations on this list.

Top ten UK sectors of foreign-born workers, 2015

| Sector | Workforce share of all migrants |

|---|---|

| Manufacture of food products | 41% |

| Manufacture of wearing apparel | 34% |

| Domestic personnel | 31% |

| Food and beverage service activities | 28% |

| Accommodation | 28% |

| Security | 27% |

| Computer programming and consultancy | 26% |

| Services to buildings and landscape | 26% |

| Land transport | 25% |

| Warehousing | 24% |

In 2015, 42% of workers in elementary process plant occupations (e.g. industry cleaning process occupation and packers, bottlers, canners and fillers), 36% of workers process operatives (i.e food, drink and tobacco process; glass and ceramics process operatives; textile process operatives; chemical and related process operatives; rubber and plastic process operatives; metal making and treating process and electroplaters) and 35% in cleaning and housekeeping managers and supervisions were foreign- born. The increase in the share of migrant labour has been greatest among process operatives (e.g. food, drink and tobacco process operatives, plastics process operatives, chemical and related process operatives) up from 8.5% in 2002 to 36% in 2015.

The post Accession flows, the rise of UKIP and Brexit

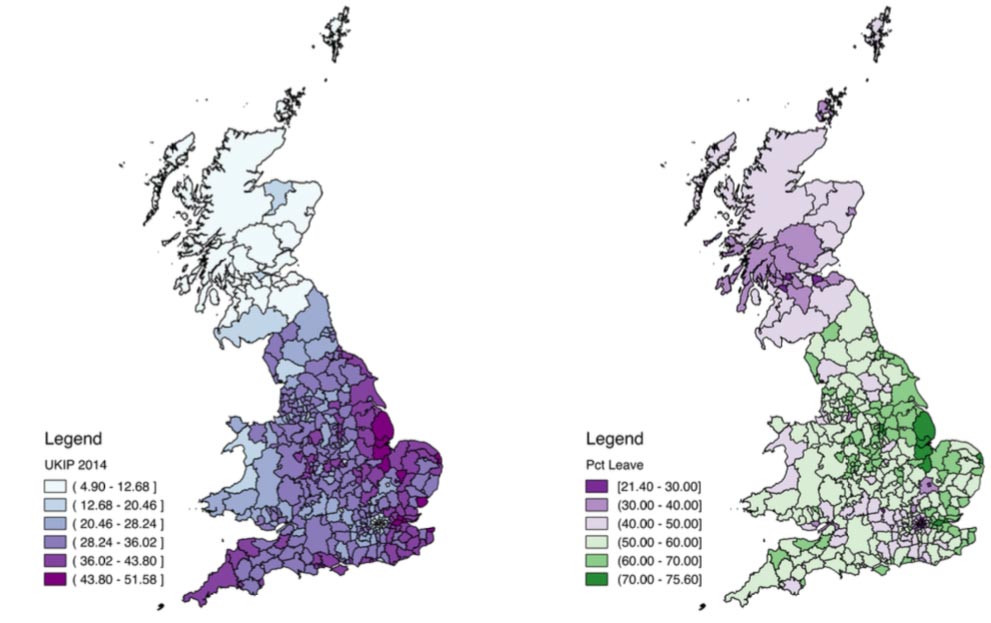

Prior support for UKIP in various areas of the UK translates nearly one-to-one into leave votes in the EU referendum, making the evolution of UKIP vote shares over time an important window into understanding how political preferences shifted in the run-up to the 2016 EU referendum.

The Becker and Fetzer study strongly suggest that the anti-EU party UKIP gained considerable support in areas that received a lot of migrants from Eastern Europe. Voters shifted away from pro-European parties towards anti-EU parties. The rise of UKIP in the European Parliament also gave the party more influence in domestic politics and put the two-party political system in the UK under strain. The challenge arising from UKIP is seen as having contributed to David Cameron being pushed by his own Conservative Party to call for a referendum in the first place.

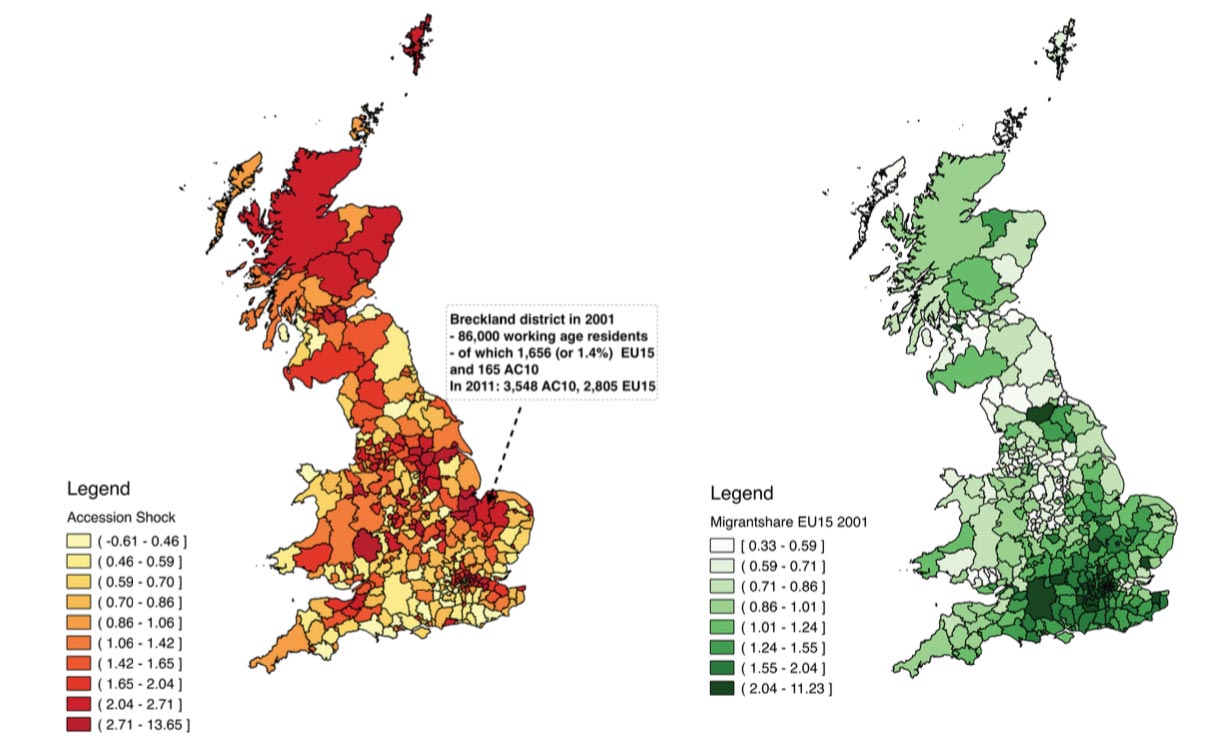

The results highlight that migration from Eastern Europe was distinct from past migration from Europe: migrants that arrived after 2004 from Eastern Europe were predominantly low skilled and settled in areas that saw little previous EU migration (see Figures 2 and 3).

For example, East Europeans that arrived prior to EU accession predominantly moved to London (around 60%), which indicates that they were more likely to serve the higher average skill London labour market. Of the East European migrants arriving after 2004, only a minority moved to London (28%), while the vast remainder moved to less affluent areas with limited prior exposure of migration from Eastern Europe. This distinct change in the patterns of migration contributed to the growth of anti-EU sentiment.

There is clear evidence that migration from Eastern Europe affected labour market outcomes. Wages at the bottom end of the earnings distribution grew disproportionately less in areas that saw in-migration from Eastern Europe.

So where does this leave us?

Its clear that the social democratic Left is struggling almost everywhere in the old developed liberal economies. Why that is happening is complex and has many causes although I would argue that almost all the reasons are tied up with the relationship between the nation state and the national foundations of social solidarity and democracy on the one hand, and the various transnational processes that are tearing at the fabric of the nation state on the other (I hope to write more on this shortly). In the middle of all this the issue of migration and the free flow of labour across borders is central because it is migration flows, and the resulting economic, social and cultural shocks the flows are causing, that is the driver of the agitation that is pushing so many citizens, particularly from the poorer end of the spectrum, towards populist and nationalist parties and leaders on the right.

The problem for the Left, especially in the UK, is that it has slowly accumulated over decades a series of positions that are utterly out of touch with how many people actually think, and crucially these positions politically immobilises the Left or places it all too often on the wrong side of the argument. These positions (for example ‘all migration controls are a bad thing and just code for racism and xenophobia’, or ‘the EU is great and much better than the nation state’, or ‘multiculturalism is always great’) have become solidified into hard rigid positions and prevent fresh thinking. So when a free transnational market for labour was created between countries of very different economic levels and this led to a sudden surge of mass migrations of workers into the UK it was hardly noticed by the Left and vaguely welcomed as evidence that we were moving towards a wonderful new post national world. It didn’t help that the Labour Party has become an predominantly middle class party and that its roots in the unskilled working class has atrophied. For most Labour Party members mass migration of workers into the UK has been a good thing, who doesn’t like lots of cheap and hardworking nannies, gardeners, cleaners and builders? Especially if the incomers are not actually threatening your job prospects or competing for scarce social resources that you depend on.

As discontent and worries about migration sharply increased the Left either ignored it or responded with arguments about how great migrants were for the economy. Of course the economy is not a single thing, it is composed of labour as well as capital, and the influx of low skilled cheap migrant labour is not great for everyone. Because the Left mostly hates thinking about national identity and mostly thinks that patriotism, and the preservation of national traditions and cultural identity are crass, it doesn’t understand why its arguments about the economic benefits of open borders have little purchase: most Brexit voters understood Britain might be economically worse off outside the EU but they didn’t care, they thought they might be better off as individuals and that there were things more important than a few percentage points of GDP growth.

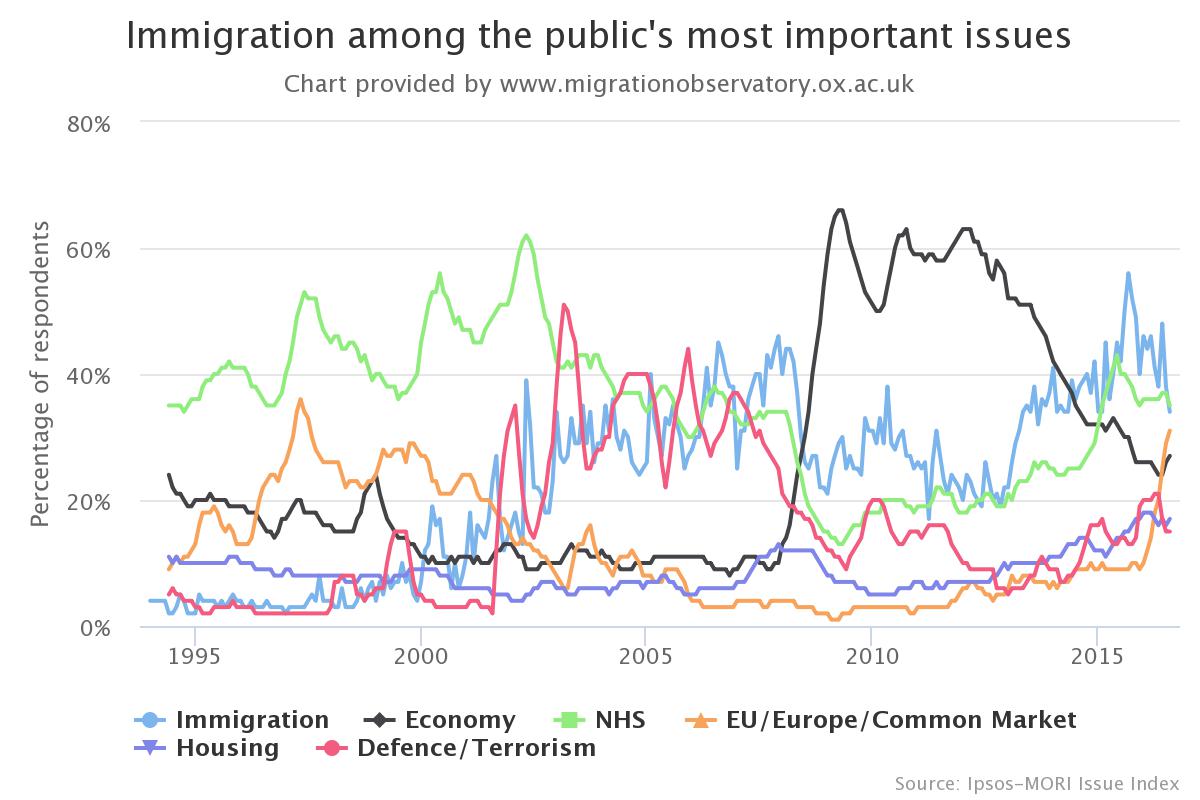

The chart below reveals the rise of immigration from a marginal concern to one of the few most-frequently named issues. Immigration and race relations were rarely mentioned by respondents as one of the ‘most important issues’ facing the country prior to 2000. As recently as December 1999, fewer than 5% of Ipsos MORI’s monthly sample gave a reply that had to do with race relations or immigration. But since then, immigration has become one of the most frequently named issues. Similar patterns emerge in polling over shorter time spans by other polling firms, including Gallup and YouGov. The response of the Left has mostly been to view concerns about immigration as either code for racism or as false consciousness whipped up my right wing media and UKIP.

Because the Left cannot address, articulate or shape the deep discontents around identity, nation, democracy and migration, the nationalist right rushes in to fill the gap. Most of the European far right movements adopted much more left wing economic policies from the late 1990s and thus mutated into nationalist populist movement and began to rapidly gain support, often from the old Left constituencies. For example French working class voters who traditionally voted communist have switched in large numbers to the National Front, similarly plenty of people have switched from the Labour Party to UKIP.

In order to reverse its decline the social democratic Left needs to do some hard thinking, and this will involve a deeply uncomfortable process of abandoning cherished and long held beliefs. Above all it needs to start thinking about the nation state.

Afternote

I just read ‘The Road to Somewhere: The Populist Revolt and the Future of Politics’ by David Goodhart, which address many of the issue raised in this post. I would highly recommend it.